Source: Voxpedia - Voting Rights Act of 1965

The

Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of

federal legislation in the

United States that prohibits racial discrimination in

voting.

[7][8] It was signed into law by

President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the

Civil Rights Movement on August 6, 1965, and

Congress later amended the Act five times to expand its protections.

[7] Designed to enforce the

voting rights guaranteed by the

Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution, the Act secured voting rights for

racial minorities throughout the country, especially in the

South. According to the

U.S. Department of Justice, the Act is considered to be the most effective piece of

civil rights legislation ever enacted in the country.

[9]

The Act contains numerous provisions that regulate election administration. The Act's "general provisions" provide nationwide protections for voting rights. Section 2 is a general provision that prohibits every

state and

local governmentfrom imposing any voting law that results in discrimination against racial or language minorities. Other general provisions specifically outlaw

literacy tests and similar devices that were historically used to disenfranchise racial minorities.

The Act also contains "special provisions" that apply to only certain jurisdictions. A core special provision is the Section 5 preclearance requirement, which prohibits certain jurisdictions from implementing any change affecting voting without receiving preapproval from the

U.S. Attorney General or the

U.S. District Court for D.C. that the change does not discriminate against protected minorities.

[10] Another special provision requires jurisdictions containing significant language minority populations to provide

bilingual ballots and other election materials.

...

Impact[edit]

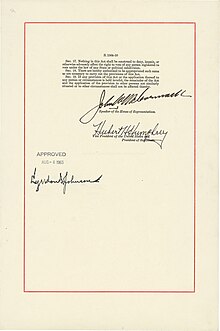

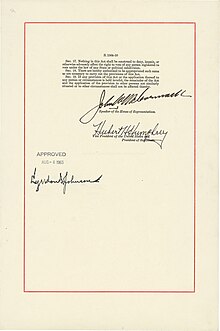

Final page of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed by President

Lyndon B. Johnson, President of the Senate

Hubert Humphrey, and Speaker of the House

John McCormack

After its enactment in 1965, the law immediately decreased racial discrimination in voting. The suspension of literacy tests and assignments of federal examiners and observers allowed for high numbers of racial minorities to register to vote.

[58] Nearly 250,000 African Americans registered in 1965, one-third of whom were registered by federal examiners.

[116] In covered jurisdictions, less than one-third (29.3%) of the African American population was registered in 1965; by 1967, this number increased to more than half (52.1%),

[58] and a majority of African American residents became registered to vote in 9 of the 13 Southern states.

[116] Similar increases were seen in the number of African Americans elected to office: between 1965 and 1985, African Americans elected as state legislators in the 11 former

Confederate states increased from 3 to 176.

[117] Nationwide, the number of African American elected officials increased from 1,469 in 1970 to 4,912 in 1980.

[84] By 2011, the number was approximately 10,500.

[118] Similarly, registration rates for language minority groups increased after Congress enacted the bilingual election requirements in 1975 and amended them in 1992. In 1973, the percent of Hispanics registered to vote was 34.9%; by 2006, that amount nearly doubled. The number of Asian Americans registered to vote in 1996 increased 58% by 2006.

[42]

The Act has also been credited with playing a role in ending the violent 1965

Watts riots, which came to an end the day after it was signed.

[119][120]

...

After the Act's initial success in combating tactics designed to deny minorities access to the polls, the Act became predominately used as a tool to challenge racial vote dilution.

[58] Starting in the 1970s, the Attorney General commonly raised Section 5 objections to voting changes that decreased the effectiveness of racial minorities' votes, including discriminatory

annexations, redistricting plans, and election methods such as at-large election systems, runoff election requirements, and prohibitions on bullet voting.

[102] In total, 81% (2,541) of preclearance objections made between 1965 and 2006 were based on vote dilution.

[102] Claims brought under Section 2 have also predominately concerned vote dilution.

[58] Between the 1982 creation of the Section 2 results test and 2006, at least 331 Section 2 lawsuits resulted in published judicial opinions. In the 1980s, 60% of Section 2 lawsuits challenged at-large election systems; in the 1990s, 37.2% challenged at-large election systems and 38.5% challenged redistricting plans. Overall, plaintiffs succeeded in 37.2% of the 331 lawsuits, and they were more likely to succeed in lawsuits brought against covered jurisdictions.

[121]

By enfranchising racial minorities, the Act facilitated a

political realignment of the Democratic and Republican parties. Between 1890 and 1965, minority disenfranchisement allowed conservative Southern Democrats to dominate

Southern politics. After Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Act into law, newly enfranchised racial minorities began to vote for liberal Democratic candidates throughout the South, and Southern white conservatives began to switch their party registration from Democrat to Republican en masse.

[122] These dual trends caused the two parties to ideologically polarize, with the Democratic Party becoming more liberal and the Republican Party becoming more conservative.

[122] The trends also created competition between the two parties,

[122] which Republicans capitalized on by implementing the

Southern strategy.

[123] Over the subsequent decades, the creation of majority-minority districts to remedy racial vote dilution claims also contributed to these developments. By packing liberal-leaning racial minorities into small numbers of majority-minority districts, large numbers of surrounding districts became more solidly white, conservative, and Republican. While this increased the elected representation of racial minorities as intended, it also decreased white Democratic representation and increased the representation of Republicans overall.

[122]

...