You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Raptor of Spain

- Thread starter MNP

- Start date

2.78 Maps

As you can see North Africa has split into several small states and Spaña. All are at least nominally Christian (except Tripoli!), though the more eastern areas have Muslim minorities of various sects.

Trading Centers of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Green are Sicilian, Red are Zaran. The Zarans are less successful than the Sicilians but they have the bulk of the non-Imperial Black Sea trade. In most places there are exclusive contracts. Zarans can trade in green ports and Sicilians in red but they aren't favored like someone from the other place would be. Antioch is special, as they both have trading centers there. Notice how Spaña favors the Sicilians obviously over the Zarans. Spañan trading centers aren't shown but they have a presence in Antioch, Acre, Crete, Cyprus and Corfu (since they own Corfu still).

As you can see North Africa has split into several small states and Spaña. All are at least nominally Christian (except Tripoli!), though the more eastern areas have Muslim minorities of various sects.

Trading Centers of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Green are Sicilian, Red are Zaran. The Zarans are less successful than the Sicilians but they have the bulk of the non-Imperial Black Sea trade. In most places there are exclusive contracts. Zarans can trade in green ports and Sicilians in red but they aren't favored like someone from the other place would be. Antioch is special, as they both have trading centers there. Notice how Spaña favors the Sicilians obviously over the Zarans. Spañan trading centers aren't shown but they have a presence in Antioch, Acre, Crete, Cyprus and Corfu (since they own Corfu still).

Anything of note about any of these particular statelets? Two nice maps there, MNP.As you can see North Africa has split into several small states and Spaña. All are at least nominally Christian (except Tripoli!), though the more eastern areas have Muslim minorities of various sects.

Hard to say exactly. It's hard to determine the ratio in our timeline (most are Arab-Berber or Arabized-Berber) but I'd have to say heavily Berber in the west. You're going to find hardly any Arabs along the West African coastline for instance. However in Libya you're going to see a sizable Arab population. Definitely a lot more Arabization there even than our timeline because the Arabs that were spread across the western Maghreb were instead concentrated in Libya. Most of the Arab population west of Tripoli is in lands ruled by Tunis.What's the ratio between Berbers and Arabs in North Africa ITTL?

Tlemsen was taken over from the Spaniards during the civil war. Being on the edge of the kingdom and not a port there was not much loyalty and the loss of order caused them to switch to someone else. Tiaret did not have coastal territory until the Spaniards gave them territories centered on Tenes. Letting Tlemsen go and not taking Tenes was part of the price Spaña paid to get Dzayer. Tiaret has a small Jewish enclave.Anything of note about any of these particular statelets? Two nice maps there, MNP.

Thanks for the info. Is there any sort of relationship - either officially or unofficially - between any of the states?Tlemsen was taken over from the Spaniards during the civil war. Being on the edge of the kingdom and not a port there was not much loyalty and the loss of order caused them to switch to someone else. Tiaret did not have coastal territory until the Spaniards gave them territories centered on Tenes. Letting Tlemsen go and not taking Tenes was part of the price Spaña paid to get Dzayer. Tiaret has a small Jewish enclave.

I suppose I'm asking how much influence and/or control Spain has over Tlemsen and Tiaret, or if they're more friendly to Tunis, whatever the religious differences might be.

200,000+ VIEWS!

200,000+ VIEWS! Thank you! That is fantastic! This Timeline could only go on so long because of the readers. It sounds cliche, but I couldn't have done it without you guys.

The next update is drafted and I will be editing it tonight for post tomorrow. It might answer some of Geordie's questions.

200,000+ VIEWS! Thank you! That is fantastic! This Timeline could only go on so long because of the readers. It sounds cliche, but I couldn't have done it without you guys.

The next update is drafted and I will be editing it tonight for post tomorrow. It might answer some of Geordie's questions.

Massive congratulations, MNP. I must say, you do deserve it.200,000+ VIEWS! Thank you! That is fantastic! This Timeline could only go on so long because of the readers. It sounds cliche, but I couldn't have done it without you guys.

Plus, this totally ignores the fact that I had at least 5 of your pages (cycling through to the present, not the same 5!) up in offline for weeks as I caught up.

Good stuff. I shall have to look tomorrow, as I'm off to bed now!The next update is drafted and I will be editing it tonight for post tomorrow. It might answer some of Geordie's questions.

2.79

2.79 - Sustainer

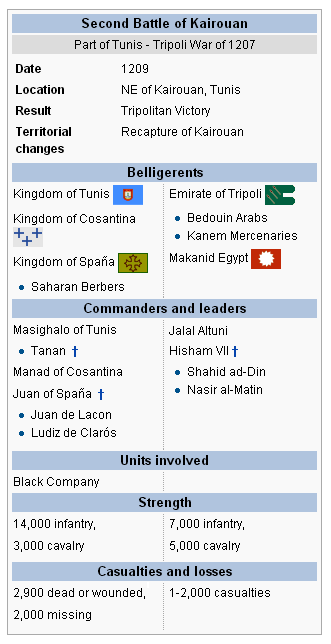

This is really part 1 of 2, with the second part with the battle of Kairouan and its aftermath coming next week. As you can see, Spaña and Egypt are both dragged in. Not quite as flashy as last time. Also sorry the map is just a fancier version of the one above!

2.79 - Sustainer

When Rolando II raided Tripoli in 1173 there were no reprisals. The Makanid Caliphs of Egypt were grown weak. Their ambitions broken on the spears of the Eastern Empire, their influence crushed by Spañan ships. Revolts broke out and were suppressed only with the help of Sudanese and Turkish mercenaries. This was the first time large numbers of Turks came into the near-east. The best of the mercenaries was Ibn Altun, who rose to command an elite Turkish division. Fearing Ibn Altun’s popularity the Caliph sent him west to Tripoli to reorganize the province to defend against Christian attacks.

Ibn Altun found the province divided by ethnic loyalties. The majority Berber population were agriculturalists and sedentary pastoralists concentrated near the coast. In the more arid lands to the south the bedouin driven east by the Spaniards and their Berber allies, held sway. Because the nomadic lifestyle of the bedouin clashed with those of the Berbers, there was friction between them. The Arab aristocracy was more concerned with enriching itself at minimal effort than governance. Ibn Altun was unable to get them to be more proactive and finally summoned more of his men from the east to depose the emir by force. The Arab lords were crushed and the emir captured and sent to al-Askar.[1]

Ibn Altun proved himself able in more than war, restoring order, reforming the administration and securing the support of the Sufri religious community despite his own Sunni theology. The government in al-Askar tolerated him. The Caliph was old, and they lacked the manpower to remove him by force. For his part, Ibn Altun acknowledged the Caliph and sent annual tributes.

The reign of Ibn Altun (r. 1182-1198) reversed the decline of Tripoli. When Sufi radicals seized Barqa[2] in 1185, he recaptured the province for the Makanids. His reward was its governorship under similar terms to that of Tripoli. Turning south he engaged in a long ultimately successful war against the Kanem Empire[3] for greater control of the trade routes. By this he won the allegiance of the bedouin who were the main guardians of those routes.

After his death in 1198, his son Jalal Altuni assumed power. He was young, but proven in the war against the Kanem and there was little opposition to his rule in Tripoli or Barqa. Immediately upon assuming leadership, Jalal made contracts with the Zarans who wanted to break the stranglehold of the Spaniards and Sicilians on the African trade. Using their money and expertise, he rapidly expanded his navy and raided Sicilian and Tunisian ports like Malta and Capès. When Masighalo of Tunis invaded him, Jalal defeated him in the lands of Zuwara and Masighalo was obliged to call upon the Spaniards to help fortify his lands.

Jalal gave refuge to the Sicilians but took time to carefully plan out his attack. The renegades were able to establish contact with several partisans on the island who kept them apprised of events. A trade war had erupted between the Sicilians and Zarans in the Aegean. Constantinople allowed it in order to extract better agreements by playing off both sides but they still had to tread carefully and avoid damaging imperial property. This meant a war fought primarily at sea and over time more and more Sicilian ships were sent to east.

As he prepared his navy, Jalal helped the renegades assemble an army made of the Greek and Dalmatian mercenaries with a few of his own levies for strengthening. They contacted their few remaining allies in Sicily and urged them to make ready.

The attack came in 1204 when half the Sicilian fleet was in the Aegean. The Muslims and Sicilian renegades launched a full assault on Messina. The renegades took the city by surprise while their partisans seized large parts of Calabria. In the coming months only Reggio would hold out, and that because Jalal’s fleet was needed to escort the renegades in their march south along the coast.

The renegades swept all before them, with Jalal’s bowmen and two companies of Turkish cavalry proving the difference again and again. Much of the rough north-east was taken. There were few defenders there as it was believed the terrain would hamper any real assault. In this phase the major battle of the war took place near the city of Catania, where the Muslim and Sicilian navies met in battle. The Sicilians were still short on ships and Jalal defeated and scattered them. Catania was laid siege to by land and sea. The city surrendered days before the Sicilian troops arrived from Syracuse. Consisting of noble household levies, these inexperienced Sicilian troops were swept away by the renegades and Jalal’s experienced troops. Only the troops on loan from the Mercenary Republic of Torino held against the renegade army. They were too many for the renegades to defeat and whenever they met in open battle it was the renegades there were put to flight. But they were also too few to retake any territory.

One reason for the success of the renegades was a land redistribution effort suggested by Jalal. Instead of simply taking over land from the existing lords, the renegades gave a portion of it to the existing tenants. They called it a tithe to the Lord, and it resulted in a significant degree of rural support for the renegades.

Panic gripped the Sicilians. A second attempt to besiege Catania failed when plague broke out in their camp. Jalal’s navy raided along the coast with seeming impunity. A rumor came out that the Zarans had wiped out the Sicilian enclave at Dyrrhachium. In desperation they begged the Spaniards for help and Alesso de Verada invaded Calabria in 1206.

Seeing the renegades well established, Jalal abandoned them and returned home with ships laden with plunder and slaves. At little cost to himself he had tied up the Sicilians and with some of the Spaniards. Then he set into motion the true plan, the re-conquest of Tunis.

Bedouin forces along with some Kanem mercenaries being accustomed to travel in the region would march by land. His own army of Turks, Arabs and Berbers would follow by sea making small hops along the cost. As he passed he called on the Muslims in the kingdom to follow him and live under right leaders and some responded. He was careful to respect Muslim property and disciplined his men if they looted it. The end of the campaign that year came with the fall of Capès in 1207, giving Jalal a secure foothold from which to launch further attacks. He had left fortresses behind him. They were too strong to reduce without great effort but holding the countryside he left them to wither on the vine.

The next year Jalal struck inland, following old Roman road to the northwest and relying on supplies brought through Capès. This was more heavily Christian country and was plundered to feed his army not for the sake of devastation as Jalal needed to move quickly. He turned north-east at the tiny town of Kasserine and laid siege to his target, Kairouan.

The city had fallen on hard times since its days as the capital of Umayyad and Abbasid Ifriqya. Under the Kahinid dynasty more importance had been placed on coastal cities like Susa and Sfax. Prior to their rule, the city had suffered badly during the war against the bedouin. It was also the city farthest west with a majority Muslim population.

The fall of Capès convinced Masighalo of Tunis this was no mere raid. That year he entreated his brothers for help. His brothers in Tiaret and Tlemsen were reluctant but family feeling caused them to send money. Cosantina was more welcoming. It had only been separated from Tunis upon the birth of the youngest son. Manad of Cosantina was the most likely to honor his father’s wishes and subordinate himself to his brother. There were already agreements between them to unite the two if ever one line failed.

At the same time Masighalo opened communications with the Spaniards, but the ruler of Tlemsen was far more interested in campaigning against the Genaya. Despite losing the city in his reign, Rolando II saw relations with Tlemsen as vital. It’s position posed a threat to the hinterlands around Mersa and newly-captured Dzayer. He continually strove to increase Spañan influence in the territory without antagonizing its ruler. The king declined to assist Masighalo. By this time however, Rolando II was quite old and execution of his orders was generally left to Prince Juan and his ally Prince Pedro. Pedro saw the increased piracy sure to follow an Islamic victory as a threat to Catalonian shipping, and Juan didn’t want anything to imperil his conquest of Dzayer. They secretly began stockpiling supplies and rallying support in the Councillarium for a potential eastern expedition but progress was slow.

Meanwhile Jalal met Masighalo and Manad in battle north of Kairouan. The Berber princes out numbered him slightly, but he used his Turkish cavalry to break up their formations and drove them from the field. Following this victory, the Muslims in Kairouan rose up and opened the gates of the city to Jalal. The fall of the city finally convinced the Spaniards to go along with Juan and Pedro and a major expedition was planned for 1209. By then it was hoped rebel Calabria would have fallen to Duke Alesso. But even without him the Spañan princes planned to bring enough force to bear to assure victory.

Campaign of Jalal Altuni

Though he did not think the Spaniard would act so soon, Jalal had planned for this eventuality. Upon the fall of Kairouan he declared a jihad and publicly sent to the Caliph Hisham VII in al-Askar for help. He wrote in part:

Newly come to the office, Hisham VII showed ruthlessness in dealing with brothers and uncles to secure his hold. With such a challenge before him by the hero of the west, he swore to remind the Spaniards that:

Had not Jalal humiliated all his enemies thus far? Hisham VII's heart and mind burned with dreams of glory. He mustered the greater part of the Egyptian army and set out to come to the rescue of Jalal Altuni.

___________________________

[1]Roughly “Canton City.” Makanid and Abbasid capital, a little north of Cairo.

[2]Roman Barce.

[3]These are the pre-Islamic Kanem.

Ibn Altun found the province divided by ethnic loyalties. The majority Berber population were agriculturalists and sedentary pastoralists concentrated near the coast. In the more arid lands to the south the bedouin driven east by the Spaniards and their Berber allies, held sway. Because the nomadic lifestyle of the bedouin clashed with those of the Berbers, there was friction between them. The Arab aristocracy was more concerned with enriching itself at minimal effort than governance. Ibn Altun was unable to get them to be more proactive and finally summoned more of his men from the east to depose the emir by force. The Arab lords were crushed and the emir captured and sent to al-Askar.[1]

Ibn Altun proved himself able in more than war, restoring order, reforming the administration and securing the support of the Sufri religious community despite his own Sunni theology. The government in al-Askar tolerated him. The Caliph was old, and they lacked the manpower to remove him by force. For his part, Ibn Altun acknowledged the Caliph and sent annual tributes.

The reign of Ibn Altun (r. 1182-1198) reversed the decline of Tripoli. When Sufi radicals seized Barqa[2] in 1185, he recaptured the province for the Makanids. His reward was its governorship under similar terms to that of Tripoli. Turning south he engaged in a long ultimately successful war against the Kanem Empire[3] for greater control of the trade routes. By this he won the allegiance of the bedouin who were the main guardians of those routes.

After his death in 1198, his son Jalal Altuni assumed power. He was young, but proven in the war against the Kanem and there was little opposition to his rule in Tripoli or Barqa. Immediately upon assuming leadership, Jalal made contracts with the Zarans who wanted to break the stranglehold of the Spaniards and Sicilians on the African trade. Using their money and expertise, he rapidly expanded his navy and raided Sicilian and Tunisian ports like Malta and Capès. When Masighalo of Tunis invaded him, Jalal defeated him in the lands of Zuwara and Masighalo was obliged to call upon the Spaniards to help fortify his lands.

Jalal gave refuge to the Sicilians but took time to carefully plan out his attack. The renegades were able to establish contact with several partisans on the island who kept them apprised of events. A trade war had erupted between the Sicilians and Zarans in the Aegean. Constantinople allowed it in order to extract better agreements by playing off both sides but they still had to tread carefully and avoid damaging imperial property. This meant a war fought primarily at sea and over time more and more Sicilian ships were sent to east.

As he prepared his navy, Jalal helped the renegades assemble an army made of the Greek and Dalmatian mercenaries with a few of his own levies for strengthening. They contacted their few remaining allies in Sicily and urged them to make ready.

The attack came in 1204 when half the Sicilian fleet was in the Aegean. The Muslims and Sicilian renegades launched a full assault on Messina. The renegades took the city by surprise while their partisans seized large parts of Calabria. In the coming months only Reggio would hold out, and that because Jalal’s fleet was needed to escort the renegades in their march south along the coast.

The renegades swept all before them, with Jalal’s bowmen and two companies of Turkish cavalry proving the difference again and again. Much of the rough north-east was taken. There were few defenders there as it was believed the terrain would hamper any real assault. In this phase the major battle of the war took place near the city of Catania, where the Muslim and Sicilian navies met in battle. The Sicilians were still short on ships and Jalal defeated and scattered them. Catania was laid siege to by land and sea. The city surrendered days before the Sicilian troops arrived from Syracuse. Consisting of noble household levies, these inexperienced Sicilian troops were swept away by the renegades and Jalal’s experienced troops. Only the troops on loan from the Mercenary Republic of Torino held against the renegade army. They were too many for the renegades to defeat and whenever they met in open battle it was the renegades there were put to flight. But they were also too few to retake any territory.

One reason for the success of the renegades was a land redistribution effort suggested by Jalal. Instead of simply taking over land from the existing lords, the renegades gave a portion of it to the existing tenants. They called it a tithe to the Lord, and it resulted in a significant degree of rural support for the renegades.

Panic gripped the Sicilians. A second attempt to besiege Catania failed when plague broke out in their camp. Jalal’s navy raided along the coast with seeming impunity. A rumor came out that the Zarans had wiped out the Sicilian enclave at Dyrrhachium. In desperation they begged the Spaniards for help and Alesso de Verada invaded Calabria in 1206.

* * * * *

Seeing the renegades well established, Jalal abandoned them and returned home with ships laden with plunder and slaves. At little cost to himself he had tied up the Sicilians and with some of the Spaniards. Then he set into motion the true plan, the re-conquest of Tunis.

Bedouin forces along with some Kanem mercenaries being accustomed to travel in the region would march by land. His own army of Turks, Arabs and Berbers would follow by sea making small hops along the cost. As he passed he called on the Muslims in the kingdom to follow him and live under right leaders and some responded. He was careful to respect Muslim property and disciplined his men if they looted it. The end of the campaign that year came with the fall of Capès in 1207, giving Jalal a secure foothold from which to launch further attacks. He had left fortresses behind him. They were too strong to reduce without great effort but holding the countryside he left them to wither on the vine.

The next year Jalal struck inland, following old Roman road to the northwest and relying on supplies brought through Capès. This was more heavily Christian country and was plundered to feed his army not for the sake of devastation as Jalal needed to move quickly. He turned north-east at the tiny town of Kasserine and laid siege to his target, Kairouan.

The city had fallen on hard times since its days as the capital of Umayyad and Abbasid Ifriqya. Under the Kahinid dynasty more importance had been placed on coastal cities like Susa and Sfax. Prior to their rule, the city had suffered badly during the war against the bedouin. It was also the city farthest west with a majority Muslim population.

The fall of Capès convinced Masighalo of Tunis this was no mere raid. That year he entreated his brothers for help. His brothers in Tiaret and Tlemsen were reluctant but family feeling caused them to send money. Cosantina was more welcoming. It had only been separated from Tunis upon the birth of the youngest son. Manad of Cosantina was the most likely to honor his father’s wishes and subordinate himself to his brother. There were already agreements between them to unite the two if ever one line failed.

At the same time Masighalo opened communications with the Spaniards, but the ruler of Tlemsen was far more interested in campaigning against the Genaya. Despite losing the city in his reign, Rolando II saw relations with Tlemsen as vital. It’s position posed a threat to the hinterlands around Mersa and newly-captured Dzayer. He continually strove to increase Spañan influence in the territory without antagonizing its ruler. The king declined to assist Masighalo. By this time however, Rolando II was quite old and execution of his orders was generally left to Prince Juan and his ally Prince Pedro. Pedro saw the increased piracy sure to follow an Islamic victory as a threat to Catalonian shipping, and Juan didn’t want anything to imperil his conquest of Dzayer. They secretly began stockpiling supplies and rallying support in the Councillarium for a potential eastern expedition but progress was slow.

Meanwhile Jalal met Masighalo and Manad in battle north of Kairouan. The Berber princes out numbered him slightly, but he used his Turkish cavalry to break up their formations and drove them from the field. Following this victory, the Muslims in Kairouan rose up and opened the gates of the city to Jalal. The fall of the city finally convinced the Spaniards to go along with Juan and Pedro and a major expedition was planned for 1209. By then it was hoped rebel Calabria would have fallen to Duke Alesso. But even without him the Spañan princes planned to bring enough force to bear to assure victory.

Campaign of Jalal Altuni

Though he did not think the Spaniard would act so soon, Jalal had planned for this eventuality. Upon the fall of Kairouan he declared a jihad and publicly sent to the Caliph Hisham VII in al-Askar for help. He wrote in part:

Let the commander of the Faithful and the Successor to the Successors to the Prophet take part. ... I urge you to demonstrate the favor of God and his True Faith to the renegades who descended from the fallen hawk of the west. Act, and let them not think you too feeble and besotted with earthly pleasures.

Newly come to the office, Hisham VII showed ruthlessness in dealing with brothers and uncles to secure his hold. With such a challenge before him by the hero of the west, he swore to remind the Spaniards that:

...their might depends on the sufferance of God... the time that has been given them to head the words of the Prophet runs short.

Had not Jalal humiliated all his enemies thus far? Hisham VII's heart and mind burned with dreams of glory. He mustered the greater part of the Egyptian army and set out to come to the rescue of Jalal Altuni.

___________________________

[1]Roughly “Canton City.” Makanid and Abbasid capital, a little north of Cairo.

[2]Roman Barce.

[3]These are the pre-Islamic Kanem.

This is really part 1 of 2, with the second part with the battle of Kairouan and its aftermath coming next week. As you can see, Spaña and Egypt are both dragged in. Not quite as flashy as last time. Also sorry the map is just a fancier version of the one above!

They did have it in Cairo, but with the waning of their power they moved it al-Askar (and renovated it) to increase their legitimacy by associating themselves more closely with the Abbasids who built the city. It's also a way to distance them from potential unrest and riots in Fustat/Cairo for personal protection. Something like OTL's Medina Azahara or Samara on a less extreme scale.Why don't the Makanids have their capital at Cairo?

2.80

2.80 - Moments

Sorry, this one is extra long. Think of it as a bonus for skipping a week. I hope you can follow the quick PoV changes. They're supposed to make it read faster but the format might defeat me here.

ED: The battle box indicates the Kairouan was recaptured, but this is incorrect and a remnant of an earlier draft. I'll fix it later.

2.80 - Moments

Once Rolando II gave approval for an expedition, Prince Juan, assembled and army in Africa with astonishing speed. A majority of his forces were known as “Saharan Moors”[1] tough mounted tribesmen from beyond the borders. They joined him in a steady stream as he marched east from Mersa. At Dzayer companies from Tlemsen and Tiaret were added to the army, but these were token forces furnished to satisfy the demand of their larger neighbor. From Dzayer, Juan began a march along the coast along side a flotilla of supply ships.

In Toledo, the Prince of Catalonia had a hard time forming an army. Rolando II was reluctant to send forces to Tunis and the prince was only able to draft the newest legion from the Central District.[2] Even with the Black Company offered by Don Ferran and his own Catalonians, he had to go to the royal council. They were the only ones with the armies to help. A promise of expenses paid and a chance to assert independence and influence against the king brought them around. However they refused to be subordinated to the traditional military command in general and Juan de Lacon in particular. They put forth Ludiz de Clarós from Córdoba as their leader though he was untried.

At Tunis, Juan found a few military engineers and supplies waiting for him but little in the way of reinforcements. The invasion of Calabria was reaching its climax with the siege of Reggio, the last rebel stronghold on the mainland. Annoyed but undaunted, Juan and the Berber kings set out along the Roman Road. The pace of the army was slowed by the siege engines they brought out of Tunis but with rumors of Kairouan being readied for war by the Tripolitans and the prospect of eastern reinforcements Juan was cautious.

A welcome surprise greeted them at Susa in the form of the fleet from Spaña assembled by Pedro that winter. Prince Juan was gratified to find that while fidalgin[3] Ludiz was determined to command his own troops he readily took advice from the Duke de Lacon and Almagre brothers leading the Black Company. He reported favorably on the young man in a letter to Pedro.

The Spaniards were reluctant to march inland immedaitely but Jalal’s horsemen launched vicious raids throughout the region. The Spaniards had already encountered and fought off several on the march toward Susa. Aware of the pressure Pedro was under, Juan felt he had to provide results.

On the Muslim side, Jalal Altuni left his second in charge of Kairouan and went to Capés to greet his reinforcements. Jalal expected some assistance from al-Askar, but not the presence of Caliph Hisham VII himself. While able to keep up a pleasant mask, it quickly became clear that Hisham VII was a stunted cutting from the tree of his ancestors.

Upon gaining the throne, most of Hisham’s male relatives met with mysterious accidents or simply vanished. The survivors escaped to take refuge in the Eastern Empire or with the Persians. When the summons came from Jalal, Hisham ignored the advice of his court and personally lead the army to war, bringing a number of luxuries on campaign including several favorites from his own harem.[4] On the road Jalal was forced to listen as Hisham declaimed grand schemes for asserting himself in the west and Syria. Jalal noted that while Hisham wanted the help of Jalal’s armies, Jalal himself would be left behind to guard the sea. Consequently Jalal prefered to spend time talking to the mercenary captains that made up most of Hisham’s army.

Before reaching Kairouan, Jalal received word the Spaniards were resupplying at Susa. He persuaded Hisham to continue on without him and make a grand entrance signifying the return of the city to the True Faith. Jalal would take the combined cavalry and try his best to slow the Spaniards to allow Hisham time to prepare.

Jalal avoided pitched battles with the Christians, carefully drawing the Spaniards north of Kairouan. The Spaniards exercised strong discipline, continuing their methodical march and too cool headed to take the bait but not all their allies were the same.

After a day of attacks and still stinging from the defeat Jalal inflicted on him the previous year, Tanan of Tunis could not be restrained. On a raid led by Jalal himself, Tanan set out after him with as many Tunisian soldiers as he could muster. They were gone before anyone could stop them. King Masighalo pleaded with Prince Juan to help his heir until Juan sent the Almagre brothers and the Black Company to bring him back but it was already too late. Finding him separated from the main army, Jalal struck with everything at his command an annihilated Tanan.

“Defense square!” Sancho Almagre shouted.

Even before he called, the Black Company was already moving. They were experienced soldiers and knew the stakes. Fifteen hundred men formed made a square bristling with pikes and halberds with Sancho in the center. Those in the rear pike ranks brought up large shields to deflect missiles. They knew what was coming the instant they saw the wreck of the Tunisians.

Jalal did not disappoint, arrows flew thick and fast from the Turkish horsemen, while the Arab cavalry flung heavy javelins. Wild shouts and screams accompanied the missiles, the enemy delighted at the trap they’d sprung and eager to unnerve the company. Men fell but not many, not yet. Protected by the square, crossbow men from the Catalonian coast braved the storm to launch bolts of their own, forcing the cavalry to shoot while on the move.

“Ride little brother,” he whispered.

Sancho had ordered his brother Alfonso back to the main army with his cavalry. They were too outnumbered to do any good and it was vital his brother reach the Prince. Protected from most missiles by heavy armor, Sancho quickly unlimbered his spyglass and saw several Muslim messengers galloping off to the south east. It was to be a race.

Jalal’s message to Hisham VII was brief: Come now and Allah be praised, we can take them!

Hisham needed little encouragement. He was already frustrated at stewing in Kairouan while Jalal met the enemy. The Spaniards had routed his great-grandfather’s army on Crete, this time would be different. He had already begun to move when the message reached him. Hisham would not let that arrogant upstart gain even more glory. It was time to remind him just who held the superior position. He turned his army north and ordered a fast march.

Sancho felt his stomach lurch when he saw the dust cloud to the south. They’d made an excellent showing while outnumbered but thousands of enemy infantry would drown them. A flag appeared out of the cloud, red with a white sun. He had no way of knowing how close the others were. He was about to ask for negotiations when a trumpet sounded to the east. A moment later thousands of horsemen appeared under a crimson flag with palms. The flag of Córdoba. They divided around his men, striking the enemy on two sides before they could react.

Sancho began calling orders. Two quick crossbow volleys while the pikes broke their square and began falling back. They left behind over two hundred dead and some very badly wounded. Looking at them with regret, Sancho promised himself to return.

Hisham VII saw the Spaniards frantically retreating and laughed.

“Where are you going Ibn Rushtu?” he taunted as Jalal retreated before the ferocious Spañan attack. “Do you suddenly have a crisis of faith?”

He ordered his men forward and the Spaniards gratifyingly dispersed before him. He hurried them on to meet the main Spañan army before it could form up into those frustrating squares that were so hard to break. The men shouted. They saw their enemy fleeing before them. He ignored the voices of his captains calling a halt. “On! On to victory!”

The Muslim forces crested a small rise in the ground and immediately slammed into the enemy.

Jalal waited. Toghan and Muizz hurried up to him. The plan was going well so far. Hisham was as reckless as he’d appeared after all, and as useless. His scouts had warned him when the Spaniards were coming and he’d managed to keep a rapid withdrawal under control. Hisham might be fool enough to the think the enemy horsemen were done but Jalal knew better.

“When?” Toghan asked. “How long do we wait?”

What passed between the three of them was not exactly family feeling, though they all had ancestors closely related enough. He had not known them until they preceded Hisham’s arrival but he’d recognized disaffection when he saw it. Hisham both needed and feared them. He’d seen how weak the Makanid power base was during his last trip east. This army represented a substantial commitment on the Caliph’s part and after careful shuffling, a minor one for Jalal. Sudden movement caught his eye. He whipped out his spyglass and trained it on a spot to the north. There, the signal, a black flag.

“Now!”

Hisham had no choice but to admit he was in trouble. The front line had dissolved into chaos. The Berbers broke and fled but behind them came the disciplined Spañan infantry already arrayed into formations. Sleeves of crossbowmen with pikemen in a long line. Dozens of his men went down before they could reform and raise shields. The Spaniards advanced slowly but methodically.

Run and live, they seemed to be saying. Stand and we will grind you into the dust.

It was already too late to run. The cavalry he’d thought dispersed was already reformed and on his flanks. The sides of his army were not experienced enough to stand up to that, not once they hit the Spañan infantry. He needed a miracle.

Jalal laughed as he threw a javelin at one of the fleeing horsemen. A lucky shot, it knocked the rider off his mount and he crashed to the ground allowing Jalal to walk up and take his horse. Jalal looked down a casually speared him under the arm. Intent on crushing Hisham’s men, the Spaniards had not kept sufficient watch on him and when he regrouped they were overwhelmed. Now Toghan and Muizz were visiting destruction on the flanks of the Spaniards with impunity. Hundreds of the enemy were out of the battle for the day, if not killed.

His own men reinforced Hisham as they drove against the three squares still on the field. There might have been seven or eight thousand of them holding. He spared a minute of admiration for their discipline. The contrast with their local allies was stark. Only Manad’s flag remained. He’d worked hard to make the Berbers fear him though luck had as much to do with it as anything.

Still, Hisham had suffered heavy losses. Over a thousand so far. If the Spaniards held together they could conceivably weather the attack until they ran out of water, which would be some time if he knew them. Hisham would batter them further weakening himself while Jalal got the credit for the reverses. One of the Makanid captains, Nasir al-Matin, might have seen Jalal was letting Hisham take the brunt of the attack but Nasir was hit by a bolt and in no condition to pursue his suspicions. Shahid looked at him thoughtfully but not suspicious.

Then it happened. A sudden convulsion in the right square. The banner of Sevilla dipped and there was a ripple Jalal could follow. Then the cry, heard even over the noise of battle.

“The prince, the prince is down!”

“Hit them! Push! NOW NOW!” Jalal shouted, standing in his stirrups. Others took up the call. At his side Hisham was bellowing triumph and actually quoting verses. Glaring at him in disgust, a wild idea suddenly entered Jalal’s head. Did he dare?

“My prince!” Alfonso Almagre shouted. He flew off his horse but Juan had already hit the ground, an arrow jutting from under his visor between the steel frame and mesh covering the rest of his face. Alfonso tugged off his glove and removed the prince’s helmet only to confirm what he already knew. Juan was dead.

“The prince! The prince is down!”

Others had seen, Alfonso leaped to steady the banner but the damage was done. Heads turned all around the square. The officers screamed to hold, but it was too late. The Makanid army was already surging forward, hammering the right square and the square was too stunned to react in time. It cracked open and enemy troops poured in, ripping terrible holes in the formation.

Alfonso drew his sword and stood over the body of the prince.

During the battle, an arrow struck Juan Prince of Sevilla and he died. His formation was attacked by the Muslim troops shortly after and broken. Alfonso Almagre was able to seize the body of the prince and retreat to where Duke de Lacon was trying to re-establish a defense, but attacks from Jalal Altuni’s cavalry made it difficult to maintain formation and King Masighalo and the remaining Tunisians panicked and fled. This caused Duke de Lacon’s defensive square to break entirely. The situation looked bleak. Then Sancho Almagre, his household guard and the ducal cavalry made a last stand to buy time for the rest to retreat

Most details of the stand are unknown, but all were killed by the Muslims. Strangely, there was no pursuit, nor was any advantage taken after the disaster. Later that the Spaniards learned that during the last stand of Almagre, Hisham VII was also struck down. In later years, songs would be made celebrating single combat between Sancho and the Caliph, but the event clearly belongs to genre poetry rather than history. Most Muslim accounts have Hisham VII with his men.

Upon the death of the Caliph, the Makanid empire began to eat itself. The death of so many of their family at the hands of Hisham led to no clear successor. As infighting began, various generals took sides on behalf of child or infant claimants. Chaos engulfed the Muslim east.

In Tripoli, Jalal smiled. He had all of the cavalry Hisham brought west and was already sending out quiet messages to people in Egypt. He would pick his moment. Just as he’d done with Hisham VII when he stood behind the Successor to the Successors of Mohammad and, after victory was assured, calmly plunged a sword into the back of his neck.

___________________________

[1]As noted before, Moor here means “Berbers not under the rule of Spaña.”

[2]During the succession war, the entire state was divided into military districts, but these are to formalize which units are responsible for which areas and do not reflect political or administrative divisions. The provinces remain the same as ever.

[3]Meaning “son of someone.” Spelling and meaning are slightly changed from OTL to reflect the greater permanence.

[4]Longtime readers with exceptional memories might recall the earlier Makanids were noted for eschewing the harem and strict adherence to the 4-wives rule.

In Toledo, the Prince of Catalonia had a hard time forming an army. Rolando II was reluctant to send forces to Tunis and the prince was only able to draft the newest legion from the Central District.[2] Even with the Black Company offered by Don Ferran and his own Catalonians, he had to go to the royal council. They were the only ones with the armies to help. A promise of expenses paid and a chance to assert independence and influence against the king brought them around. However they refused to be subordinated to the traditional military command in general and Juan de Lacon in particular. They put forth Ludiz de Clarós from Córdoba as their leader though he was untried.

At Tunis, Juan found a few military engineers and supplies waiting for him but little in the way of reinforcements. The invasion of Calabria was reaching its climax with the siege of Reggio, the last rebel stronghold on the mainland. Annoyed but undaunted, Juan and the Berber kings set out along the Roman Road. The pace of the army was slowed by the siege engines they brought out of Tunis but with rumors of Kairouan being readied for war by the Tripolitans and the prospect of eastern reinforcements Juan was cautious.

A welcome surprise greeted them at Susa in the form of the fleet from Spaña assembled by Pedro that winter. Prince Juan was gratified to find that while fidalgin[3] Ludiz was determined to command his own troops he readily took advice from the Duke de Lacon and Almagre brothers leading the Black Company. He reported favorably on the young man in a letter to Pedro.

The Spaniards were reluctant to march inland immedaitely but Jalal’s horsemen launched vicious raids throughout the region. The Spaniards had already encountered and fought off several on the march toward Susa. Aware of the pressure Pedro was under, Juan felt he had to provide results.

On the Muslim side, Jalal Altuni left his second in charge of Kairouan and went to Capés to greet his reinforcements. Jalal expected some assistance from al-Askar, but not the presence of Caliph Hisham VII himself. While able to keep up a pleasant mask, it quickly became clear that Hisham VII was a stunted cutting from the tree of his ancestors.

Upon gaining the throne, most of Hisham’s male relatives met with mysterious accidents or simply vanished. The survivors escaped to take refuge in the Eastern Empire or with the Persians. When the summons came from Jalal, Hisham ignored the advice of his court and personally lead the army to war, bringing a number of luxuries on campaign including several favorites from his own harem.[4] On the road Jalal was forced to listen as Hisham declaimed grand schemes for asserting himself in the west and Syria. Jalal noted that while Hisham wanted the help of Jalal’s armies, Jalal himself would be left behind to guard the sea. Consequently Jalal prefered to spend time talking to the mercenary captains that made up most of Hisham’s army.

Before reaching Kairouan, Jalal received word the Spaniards were resupplying at Susa. He persuaded Hisham to continue on without him and make a grand entrance signifying the return of the city to the True Faith. Jalal would take the combined cavalry and try his best to slow the Spaniards to allow Hisham time to prepare.

Jalal avoided pitched battles with the Christians, carefully drawing the Spaniards north of Kairouan. The Spaniards exercised strong discipline, continuing their methodical march and too cool headed to take the bait but not all their allies were the same.

After a day of attacks and still stinging from the defeat Jalal inflicted on him the previous year, Tanan of Tunis could not be restrained. On a raid led by Jalal himself, Tanan set out after him with as many Tunisian soldiers as he could muster. They were gone before anyone could stop them. King Masighalo pleaded with Prince Juan to help his heir until Juan sent the Almagre brothers and the Black Company to bring him back but it was already too late. Finding him separated from the main army, Jalal struck with everything at his command an annihilated Tanan.

* * * * *

“Defense square!” Sancho Almagre shouted.

Even before he called, the Black Company was already moving. They were experienced soldiers and knew the stakes. Fifteen hundred men formed made a square bristling with pikes and halberds with Sancho in the center. Those in the rear pike ranks brought up large shields to deflect missiles. They knew what was coming the instant they saw the wreck of the Tunisians.

Jalal did not disappoint, arrows flew thick and fast from the Turkish horsemen, while the Arab cavalry flung heavy javelins. Wild shouts and screams accompanied the missiles, the enemy delighted at the trap they’d sprung and eager to unnerve the company. Men fell but not many, not yet. Protected by the square, crossbow men from the Catalonian coast braved the storm to launch bolts of their own, forcing the cavalry to shoot while on the move.

“Ride little brother,” he whispered.

Sancho had ordered his brother Alfonso back to the main army with his cavalry. They were too outnumbered to do any good and it was vital his brother reach the Prince. Protected from most missiles by heavy armor, Sancho quickly unlimbered his spyglass and saw several Muslim messengers galloping off to the south east. It was to be a race.

* * * * *

Jalal’s message to Hisham VII was brief: Come now and Allah be praised, we can take them!

Hisham needed little encouragement. He was already frustrated at stewing in Kairouan while Jalal met the enemy. The Spaniards had routed his great-grandfather’s army on Crete, this time would be different. He had already begun to move when the message reached him. Hisham would not let that arrogant upstart gain even more glory. It was time to remind him just who held the superior position. He turned his army north and ordered a fast march.

* * * * *

Sancho felt his stomach lurch when he saw the dust cloud to the south. They’d made an excellent showing while outnumbered but thousands of enemy infantry would drown them. A flag appeared out of the cloud, red with a white sun. He had no way of knowing how close the others were. He was about to ask for negotiations when a trumpet sounded to the east. A moment later thousands of horsemen appeared under a crimson flag with palms. The flag of Córdoba. They divided around his men, striking the enemy on two sides before they could react.

Sancho began calling orders. Two quick crossbow volleys while the pikes broke their square and began falling back. They left behind over two hundred dead and some very badly wounded. Looking at them with regret, Sancho promised himself to return.

* * * * *

Hisham VII saw the Spaniards frantically retreating and laughed.

“Where are you going Ibn Rushtu?” he taunted as Jalal retreated before the ferocious Spañan attack. “Do you suddenly have a crisis of faith?”

He ordered his men forward and the Spaniards gratifyingly dispersed before him. He hurried them on to meet the main Spañan army before it could form up into those frustrating squares that were so hard to break. The men shouted. They saw their enemy fleeing before them. He ignored the voices of his captains calling a halt. “On! On to victory!”

The Muslim forces crested a small rise in the ground and immediately slammed into the enemy.

* * * * *

Jalal waited. Toghan and Muizz hurried up to him. The plan was going well so far. Hisham was as reckless as he’d appeared after all, and as useless. His scouts had warned him when the Spaniards were coming and he’d managed to keep a rapid withdrawal under control. Hisham might be fool enough to the think the enemy horsemen were done but Jalal knew better.

“When?” Toghan asked. “How long do we wait?”

What passed between the three of them was not exactly family feeling, though they all had ancestors closely related enough. He had not known them until they preceded Hisham’s arrival but he’d recognized disaffection when he saw it. Hisham both needed and feared them. He’d seen how weak the Makanid power base was during his last trip east. This army represented a substantial commitment on the Caliph’s part and after careful shuffling, a minor one for Jalal. Sudden movement caught his eye. He whipped out his spyglass and trained it on a spot to the north. There, the signal, a black flag.

“Now!”

* * * * *

Hisham had no choice but to admit he was in trouble. The front line had dissolved into chaos. The Berbers broke and fled but behind them came the disciplined Spañan infantry already arrayed into formations. Sleeves of crossbowmen with pikemen in a long line. Dozens of his men went down before they could reform and raise shields. The Spaniards advanced slowly but methodically.

Run and live, they seemed to be saying. Stand and we will grind you into the dust.

It was already too late to run. The cavalry he’d thought dispersed was already reformed and on his flanks. The sides of his army were not experienced enough to stand up to that, not once they hit the Spañan infantry. He needed a miracle.

* * * * *

Jalal laughed as he threw a javelin at one of the fleeing horsemen. A lucky shot, it knocked the rider off his mount and he crashed to the ground allowing Jalal to walk up and take his horse. Jalal looked down a casually speared him under the arm. Intent on crushing Hisham’s men, the Spaniards had not kept sufficient watch on him and when he regrouped they were overwhelmed. Now Toghan and Muizz were visiting destruction on the flanks of the Spaniards with impunity. Hundreds of the enemy were out of the battle for the day, if not killed.

His own men reinforced Hisham as they drove against the three squares still on the field. There might have been seven or eight thousand of them holding. He spared a minute of admiration for their discipline. The contrast with their local allies was stark. Only Manad’s flag remained. He’d worked hard to make the Berbers fear him though luck had as much to do with it as anything.

Still, Hisham had suffered heavy losses. Over a thousand so far. If the Spaniards held together they could conceivably weather the attack until they ran out of water, which would be some time if he knew them. Hisham would batter them further weakening himself while Jalal got the credit for the reverses. One of the Makanid captains, Nasir al-Matin, might have seen Jalal was letting Hisham take the brunt of the attack but Nasir was hit by a bolt and in no condition to pursue his suspicions. Shahid looked at him thoughtfully but not suspicious.

Then it happened. A sudden convulsion in the right square. The banner of Sevilla dipped and there was a ripple Jalal could follow. Then the cry, heard even over the noise of battle.

“The prince, the prince is down!”

“Hit them! Push! NOW NOW!” Jalal shouted, standing in his stirrups. Others took up the call. At his side Hisham was bellowing triumph and actually quoting verses. Glaring at him in disgust, a wild idea suddenly entered Jalal’s head. Did he dare?

* * * * *

“My prince!” Alfonso Almagre shouted. He flew off his horse but Juan had already hit the ground, an arrow jutting from under his visor between the steel frame and mesh covering the rest of his face. Alfonso tugged off his glove and removed the prince’s helmet only to confirm what he already knew. Juan was dead.

“The prince! The prince is down!”

Others had seen, Alfonso leaped to steady the banner but the damage was done. Heads turned all around the square. The officers screamed to hold, but it was too late. The Makanid army was already surging forward, hammering the right square and the square was too stunned to react in time. It cracked open and enemy troops poured in, ripping terrible holes in the formation.

Alfonso drew his sword and stood over the body of the prince.

* * * * *

During the battle, an arrow struck Juan Prince of Sevilla and he died. His formation was attacked by the Muslim troops shortly after and broken. Alfonso Almagre was able to seize the body of the prince and retreat to where Duke de Lacon was trying to re-establish a defense, but attacks from Jalal Altuni’s cavalry made it difficult to maintain formation and King Masighalo and the remaining Tunisians panicked and fled. This caused Duke de Lacon’s defensive square to break entirely. The situation looked bleak. Then Sancho Almagre, his household guard and the ducal cavalry made a last stand to buy time for the rest to retreat

Most details of the stand are unknown, but all were killed by the Muslims. Strangely, there was no pursuit, nor was any advantage taken after the disaster. Later that the Spaniards learned that during the last stand of Almagre, Hisham VII was also struck down. In later years, songs would be made celebrating single combat between Sancho and the Caliph, but the event clearly belongs to genre poetry rather than history. Most Muslim accounts have Hisham VII with his men.

Upon the death of the Caliph, the Makanid empire began to eat itself. The death of so many of their family at the hands of Hisham led to no clear successor. As infighting began, various generals took sides on behalf of child or infant claimants. Chaos engulfed the Muslim east.

* * * * *

In Tripoli, Jalal smiled. He had all of the cavalry Hisham brought west and was already sending out quiet messages to people in Egypt. He would pick his moment. Just as he’d done with Hisham VII when he stood behind the Successor to the Successors of Mohammad and, after victory was assured, calmly plunged a sword into the back of his neck.

___________________________

[1]As noted before, Moor here means “Berbers not under the rule of Spaña.”

[2]During the succession war, the entire state was divided into military districts, but these are to formalize which units are responsible for which areas and do not reflect political or administrative divisions. The provinces remain the same as ever.

[3]Meaning “son of someone.” Spelling and meaning are slightly changed from OTL to reflect the greater permanence.

[4]Longtime readers with exceptional memories might recall the earlier Makanids were noted for eschewing the harem and strict adherence to the 4-wives rule.

Sorry, this one is extra long. Think of it as a bonus for skipping a week. I hope you can follow the quick PoV changes. They're supposed to make it read faster but the format might defeat me here.

ED: The battle box indicates the Kairouan was recaptured, but this is incorrect and a remnant of an earlier draft. I'll fix it later.

Last edited:

Seems like Tripoli is the only real winner of this war.

Yes. Egypt's a more attractive prize now. For more than just Tripoli... Though their involvement here is what begins the serious spread of Islam into the Kanem Empire, so Islam in general gained too.and even then, more for the fact they can now move eastwards.

Last edited:

It seems that the spread of Islam in that area has been delayed for at least several generations in comparison with OTL.Yes. Egypt's a more attractive prize now. For more than just Tripoli... Though their involvement here is what begins the serious spread of Islam into the Kanem Empire, so Islam in general gained too.

2.81

2.81 - Beyond Battle

So the Spaniards are okay if a bit shaky, Jalal is making his move and the eastern empire is going to try out something new. The delays in this update stem from my laptop having a quote "catastrophic" hard drive failure and from deciding just how the dynamic in the east will play out.

Oh yeah, one more thing. If anyone would like to be notified whenever I update via PM, just let me know either here or via PM. I am on a few these myself and I find it handy to have a PM when the updates come.

2.81 - Beyond Battle

The most notable effect the defeat at Kairouan in 1209 had on Spaña was that it had so little. Pedro of Catalonia heard the news from his agents in time to take decisive action. He did all he could to slow the news from reaching the populace or other parts of the government including the king while convincing the badly ill Rolando II to grant him a formal appointment as vizrey. Meanwhile he sent his oldest son with a large escort to Sevilla to lay hold of Juan’s family and bring them to the capital. While he waited for their return he distributed a list of persons who were barred from entering the capital and sent his own men into the Omeyata District to keep a close watch on the movements of the high nobility already there. It was already a fact that the Prince of Maritime Catalonia and the Royal Council were directing the actions of the General Court and he intended there to be no disruption in that regard. But to negate any challenges the Royal Council might throw up to his preeminence he needed the new Heir to hand.

“Any of the others would seek to achieve power for himself alone, with the boy as barely an afterthought,” Pedro wrote to Juan’s sister Antonina at Luz. “I recall what it was like when I endured it and I won’t have it. I ask only that my own territories be left alone. Rest easy that I will think of him as well as myself and remember I have put my fate into your hands from this moment.”

In this as in most ventures from here on, the Almagre family were his allies. Already dominating the Military District of Castille and parts of Tolosa, they tied themselves to Prince Pedro and his powerful coastal territories. While still loyal to Rolando II (they had supported him during the internal conflicts) they lent a sympathetic ear to northerners who complained about the strength of the southerners in Rolando II’s reign. They received power and influence despite their defiance of the king while their loyalty gained them little but dead sons and war costs. The northerners were partially mollified by heavy investments in cloth production in the Ebro and Tolosa, but there was no corresponding increase in political power. The old arrangements with the Royal Council from the 1180s still held and they saw a chance to adjust the balance.

In Africa, Alfonso Almagre and Juan de Lacon were able to rapidly reform the core of their army in time to beat back a few probes toward Susa. They wrote to Don Arrigo of Cerdena, Rolando II’s old ally and at his own initiative ordered them to do all they could to prevent outside interference in the Sicilian affair. With this order they were able to put heart into Ludiz de Claros, the commander of the noble levies. During the battle they had been set upon mercilessly by their Muslim counterparts and had taken the brunt of the losses. Ludiz himself longed to avenge the humiliation dealt to his family name and was able to convince a number of levies to remain. Together the three men defeated a more serious attempt Jalal’s captains mounted for Susa in 1210, though the numbers involved were significantly smaller than Kairouan the year before. The victory bought them the time needed for Manad of Cosantina to consolidate power in Tunis.

After Kairouan and the death of his son, King Masighalo was a spent force. His only other children were still quite young and the shocks of loss kept him from taking decisive action. Into the vacuum stepped his youngest brother Manad. Manad had stood with the Spaniards until the end at the battle and his men were in better shape than the Tunisians. He remained in Tunis to help his brother during the difficult time, but predictably reached out for the reins of power. Seeing in him their best option, the Spaniards threw their influence and manpower behind him as regent for his nephews. Unlike Prince Pedro however, both Manad and Alfonso had no intention of ever letting them come to power. Surviving evidence points to at least two of the boys exiled to Spaña but there is nothing on the third.

In the end, the news of the loss of the battle and some of their own troops caused friction between the Royal Council and the vizrey. However the vizrey’s troops were firmly in control of the capital and he had firm possession of the Heir. For now at least, they chose to reconcile themselves with continuing to direct the fate of the country. In the end, that direction evidenced little change. Indeed, in the coming years while the members of the Royal Council might shift or struggle among themselves (the less competent or the simply unlucky tended to lose these struggles) they largely continued the practice of weakening other nobility through wielding the state bureaucracy.

By 1212 it was clear to anyone that the Makanid Caliphate was mortally wounded. Anyone with a powerbase could and sometimes claim to represent some claimant or other, usually young usually powerless. A few of these cases might have even been genuine. Hisham VII had not been able to completely destroy his family in the time he had, after all. The most salient factions were those headed by the two commanders who had gone east with Hisham, Shahid ad-Din and Nasir al-Matin. Nasir was clearly the more skilled commander and the largest single following. His headquarters was in Ascalon. Shahid controlled the political capital Al-Askar, and Fustat to the south. Under normal circumstances holding the capital might have been enough to end the division, but Shahid was almost completely unable to project power beyond the immediate hinterland of the two cities. Nasir would have been able to drive him out had Shahid not had the backing of Jalal Altuni.

Jalal’s efforts to push farther westward were a combination of opportunism, misdirection and a desire to keep his men sharp. Jalal did not lead these commands and remained in Barqa so as not to be too far from events in Egypt. The failures after Kairouan convinced him that the Spaniards were committed to the defense of their clients. With the eastern prize ahead of him he allowed the western to lapse. Instead he gathered supplies and money and waited for the chaos to grow while communicating quietly with both Shahid (to whom he also sent some military aid), and the Turkish captains he’d suborned. During this time, a number of the Muslims in Kairouan migrated from the city to Tripoli.

When the time came, Jalal moved swiftly and made good use of his navy. He made landfall in Egypt in 1212 at Diametta and took the city without much trouble. Almost immediately a number of the smaller factions united to challenge him. This was the result of Shahid’s own efforts to form a coalition against his secret benefactor. However unbeknownst to them, Shahid had done this with the full knowledge of Jalal and at the last moment Shahid failed to support his supposed allies and so they were completely crushed by Jalal a day’s walk south of Diametta. Following the victory, Jalal had Shahid’s claimant proclaimed at the Friday prayers to show he was not seizing power for himself, at least officially. Combined with certain promises of religious reform made to the religious leaders, this had the hoped for effect and there was limited official opposition to his authority. The return of order in these regions after 2 years of lawlessness proved to be a major point in Jalal’s favor with the people as well.

With the lion’s share of the opposition wiped out, Jalal had an easy passage to Al-Askar. There was a brief moment of tension as to whether Shahid would attempt to betray Jalal, but soon Al-Askar opened to him and the westerner marched inside to the acclaim of the populace. In Al-Askar and Diametta, the immigrants from Kairouan proved themselves. They had existing contacts and connections with the western markets beyond the Easter Empire and with the final defeat of the Sicilian renegades that year, two maritime western powers once again vying for trade from the east.

It was up to Jalal to make sure that trade was protected. Once again, God seemed to be on his side. News from the east had Nasir and his greatest ally the Damascene Emir, quarreling. As best Jalal could determine they were fighting not just over precedence, but over how much aid it would be seemly to gain from the Eastern Empire. This galvanized Jalal. For him the involvement of the empire would constitute a disaster.

The Eastern Empire had once again revived itself from a decline it had experienced in the previous half-century by finally emerging victorious in their long war of attrition against the Kimeks.[1] For the first time in generations, they dominated the north bank of the Danube , while the petty principalities in the Balkans had been subsumed and Belgrade was once again their mightiest fortress on the western border. In what was considered an example of typical Greek cunning in Francia and interesting statecraft in Spaña, the Eastern Empire had paid a single year’s tribute to a Kimek invasion force in 1210. Then in 1211 an even larger invasion force advanced into the lands north of Danube only to be surrounded and annihilated by a joint force from the Empire and Hungary. So great was the slaughter that it was said nine-tenths of the Kimek men perished in the fighting though their continued survival argued against it. Regardless, the battle[2] granted the Hungarians access to the Black Sea and the Eastern Empire an opponent so badly beaten there were no attacks from the Kimeks for over a generation. Two years later the empire had mostly consolidated its power along the Danube and in 1213 formally took control of Crete in exchange for a series of subsidies to the Spaniards.

The architect of this revival was not a single mighty emperor. While there was a new dynasty on the throne in the Gabras dynasty[3], it was what they represented that was new. While they technically were a noble family and had military officers in their past, their primary form of support had not come from either the aristocratic military nobility, or the court bureaucracy. Instead they came to power predominately on the strength of the private moneyed classes. This class had come into its own in the last two centuries during a long economic expansion that saw many cities become important centers of local and regional manufacture. The capital was naturally the largest of these, but the Gabras expended effort on extensively developing cities around the Aegean instead of simply Constantinople.

The court administration was placated by both a general expansion and by delegation of greater authority in the imperial core territories effectively degrading the power of the military aristocracy. As might be expected, this was not without resistance and despite their noble blood, rebellions against the Gabras sprang up in central and eastern Anatolia. These featured both generals who claimed the throne for themselves and who proclaimed distant relatives of former imperial houses as emperor. It was not unlike what would happen to the Makanids. But there was a key difference: the Gabras won.

They did so thanks to the private wealthy. By the late 12th century they felt the old aristocracy with their wealth based on agriculture, was simply not able to effectively further their interests. They sought acceptable alternatives and when the time for blood came, they contributed enormous amounts of money to the Gabras emperors. With larger, better equipped armies they wore down the rebels and eventually gain the allegiance of some of the more experience military commanders which saw the end of the rebellion.

While the imperial core became more closed to them, the aristocracy received greater powers along the border territories and more real military power and less central interference. A massive collusion between these powerful border regions could probably over throw the emperor, but the territorial dukes dared not trust each other and imperial spy networks were very active. It was not a perfect solution, but it was a solution that bought the Gabras dynasty the time it needed to defeat the Kimeks.

The defeat of the Kimeks was proof positive that the new coalition of private interests with the emperor was a strong way forward and widespread opposition vanished. If anyone still held grudges they nursed them in secret. And now with a richer, more unified and more unitary empire, they received the request from the Emir of Damascus for help against Jalal with significant interest. As Constantine XI explained in a surviving correspondence:

___________________________

[1]The Kimeks themselves have been split into two states, the western centered on the Pannonian plain, and the east centered on the Crimea after being attacked by the Eastern Empire, Hungary and the Kyrgyz Khannate.

[2]Probably fought somewhere in northeast Wallachia.

[3]Not the historical Gabras family.

“Any of the others would seek to achieve power for himself alone, with the boy as barely an afterthought,” Pedro wrote to Juan’s sister Antonina at Luz. “I recall what it was like when I endured it and I won’t have it. I ask only that my own territories be left alone. Rest easy that I will think of him as well as myself and remember I have put my fate into your hands from this moment.”

In this as in most ventures from here on, the Almagre family were his allies. Already dominating the Military District of Castille and parts of Tolosa, they tied themselves to Prince Pedro and his powerful coastal territories. While still loyal to Rolando II (they had supported him during the internal conflicts) they lent a sympathetic ear to northerners who complained about the strength of the southerners in Rolando II’s reign. They received power and influence despite their defiance of the king while their loyalty gained them little but dead sons and war costs. The northerners were partially mollified by heavy investments in cloth production in the Ebro and Tolosa, but there was no corresponding increase in political power. The old arrangements with the Royal Council from the 1180s still held and they saw a chance to adjust the balance.

In Africa, Alfonso Almagre and Juan de Lacon were able to rapidly reform the core of their army in time to beat back a few probes toward Susa. They wrote to Don Arrigo of Cerdena, Rolando II’s old ally and at his own initiative ordered them to do all they could to prevent outside interference in the Sicilian affair. With this order they were able to put heart into Ludiz de Claros, the commander of the noble levies. During the battle they had been set upon mercilessly by their Muslim counterparts and had taken the brunt of the losses. Ludiz himself longed to avenge the humiliation dealt to his family name and was able to convince a number of levies to remain. Together the three men defeated a more serious attempt Jalal’s captains mounted for Susa in 1210, though the numbers involved were significantly smaller than Kairouan the year before. The victory bought them the time needed for Manad of Cosantina to consolidate power in Tunis.

After Kairouan and the death of his son, King Masighalo was a spent force. His only other children were still quite young and the shocks of loss kept him from taking decisive action. Into the vacuum stepped his youngest brother Manad. Manad had stood with the Spaniards until the end at the battle and his men were in better shape than the Tunisians. He remained in Tunis to help his brother during the difficult time, but predictably reached out for the reins of power. Seeing in him their best option, the Spaniards threw their influence and manpower behind him as regent for his nephews. Unlike Prince Pedro however, both Manad and Alfonso had no intention of ever letting them come to power. Surviving evidence points to at least two of the boys exiled to Spaña but there is nothing on the third.

In the end, the news of the loss of the battle and some of their own troops caused friction between the Royal Council and the vizrey. However the vizrey’s troops were firmly in control of the capital and he had firm possession of the Heir. For now at least, they chose to reconcile themselves with continuing to direct the fate of the country. In the end, that direction evidenced little change. Indeed, in the coming years while the members of the Royal Council might shift or struggle among themselves (the less competent or the simply unlucky tended to lose these struggles) they largely continued the practice of weakening other nobility through wielding the state bureaucracy.

* * * * *

By 1212 it was clear to anyone that the Makanid Caliphate was mortally wounded. Anyone with a powerbase could and sometimes claim to represent some claimant or other, usually young usually powerless. A few of these cases might have even been genuine. Hisham VII had not been able to completely destroy his family in the time he had, after all. The most salient factions were those headed by the two commanders who had gone east with Hisham, Shahid ad-Din and Nasir al-Matin. Nasir was clearly the more skilled commander and the largest single following. His headquarters was in Ascalon. Shahid controlled the political capital Al-Askar, and Fustat to the south. Under normal circumstances holding the capital might have been enough to end the division, but Shahid was almost completely unable to project power beyond the immediate hinterland of the two cities. Nasir would have been able to drive him out had Shahid not had the backing of Jalal Altuni.

Jalal’s efforts to push farther westward were a combination of opportunism, misdirection and a desire to keep his men sharp. Jalal did not lead these commands and remained in Barqa so as not to be too far from events in Egypt. The failures after Kairouan convinced him that the Spaniards were committed to the defense of their clients. With the eastern prize ahead of him he allowed the western to lapse. Instead he gathered supplies and money and waited for the chaos to grow while communicating quietly with both Shahid (to whom he also sent some military aid), and the Turkish captains he’d suborned. During this time, a number of the Muslims in Kairouan migrated from the city to Tripoli.

When the time came, Jalal moved swiftly and made good use of his navy. He made landfall in Egypt in 1212 at Diametta and took the city without much trouble. Almost immediately a number of the smaller factions united to challenge him. This was the result of Shahid’s own efforts to form a coalition against his secret benefactor. However unbeknownst to them, Shahid had done this with the full knowledge of Jalal and at the last moment Shahid failed to support his supposed allies and so they were completely crushed by Jalal a day’s walk south of Diametta. Following the victory, Jalal had Shahid’s claimant proclaimed at the Friday prayers to show he was not seizing power for himself, at least officially. Combined with certain promises of religious reform made to the religious leaders, this had the hoped for effect and there was limited official opposition to his authority. The return of order in these regions after 2 years of lawlessness proved to be a major point in Jalal’s favor with the people as well.

With the lion’s share of the opposition wiped out, Jalal had an easy passage to Al-Askar. There was a brief moment of tension as to whether Shahid would attempt to betray Jalal, but soon Al-Askar opened to him and the westerner marched inside to the acclaim of the populace. In Al-Askar and Diametta, the immigrants from Kairouan proved themselves. They had existing contacts and connections with the western markets beyond the Easter Empire and with the final defeat of the Sicilian renegades that year, two maritime western powers once again vying for trade from the east.

It was up to Jalal to make sure that trade was protected. Once again, God seemed to be on his side. News from the east had Nasir and his greatest ally the Damascene Emir, quarreling. As best Jalal could determine they were fighting not just over precedence, but over how much aid it would be seemly to gain from the Eastern Empire. This galvanized Jalal. For him the involvement of the empire would constitute a disaster.

* * * * *

The Eastern Empire had once again revived itself from a decline it had experienced in the previous half-century by finally emerging victorious in their long war of attrition against the Kimeks.[1] For the first time in generations, they dominated the north bank of the Danube , while the petty principalities in the Balkans had been subsumed and Belgrade was once again their mightiest fortress on the western border. In what was considered an example of typical Greek cunning in Francia and interesting statecraft in Spaña, the Eastern Empire had paid a single year’s tribute to a Kimek invasion force in 1210. Then in 1211 an even larger invasion force advanced into the lands north of Danube only to be surrounded and annihilated by a joint force from the Empire and Hungary. So great was the slaughter that it was said nine-tenths of the Kimek men perished in the fighting though their continued survival argued against it. Regardless, the battle[2] granted the Hungarians access to the Black Sea and the Eastern Empire an opponent so badly beaten there were no attacks from the Kimeks for over a generation. Two years later the empire had mostly consolidated its power along the Danube and in 1213 formally took control of Crete in exchange for a series of subsidies to the Spaniards.