May your mom rest in peace. I really hope you'll find energy and joy not only to keep on working on this amazing tale you created, but to keep on living, working, and being the great family man and person I'm absolutely sure you are. May God be with you.It's been almost two months since the last post. I'd thought I would be back sooner, finishing my chapter, moving this love letter to the 70s along. Basking in the glory of my new house.

48 hours before the move, my mother died suddenly, in a hospital ER, my brother and I having to decide no more measures should be taken to save her. I lost my dad a long time ago, and this has wrecked me. There was so much unsaid, unasked, so many years left. And she was supposed to be our first guest here, us finally having the space for her to stay comfortably.

I've done my best, working and getting the house put together, hanging the art and the photos, building new furniture where needed, and sorting through everything in my mom's house with my brother and his wife, making the three hours drive up that was always so happy before and now felt empty. The ghosts of memory are everywhere and it's haunted my waking hours and my dreams.

I haven't any words for this tale and it saddens me. I want to write and I can't write. I want to play my guitar and an outbreak of neuropathy has made that impossible, likely brought on by overwork and stress. I want to sleep but doing so is often not restful.

I don't know when this story will return. I will do my best for it to be sooner rather than later. I am sorry I cannot offer more right now, but I am lost in so many ways. From the misty wooded views of my backyard, farewell for now.

View attachment 786339

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Texas Two-Step: Nixon nominates Connally as VP in 1973

- Thread starter wolverinethad

- Start date

May she rest in peace. You are a good person We will be here for you later. We love you.

Football, turkey, and Big Bad John -- November 28, 1974

It had been surprising, really, the Central Committee man thought as the Politburo members trudged out of their meeting. Their inability to pick a successor to old Leonid has created true collective rule, and collective rule could better be defined as paralysis. The belief that Yuri Andropov would just slide into Brezhnev’s warm chair was upended by the Korean misadventure. Tensions continued to remain high, but at least nobody was actively shooting at each other. Regardless, it was enough to where a faction under Kosygin had managed to prevent Andropov’s ascension—it was an unwritten but hard rule that votes had to be unanimous when it involved the promotion to the Politburo or a secretariat position. Right now, Andropov held a majority, but it wasn’t even close to a majority where he’d feel comfortable calling a vote. Kosygin might’ve been marginalized by Brezhnev, but he still held a lot of power, whereas Andropov had only been a full member of the Politburo since 1971. Both men were now jockeying for position with their colleagues while showing the world a united front—except that it was increasingly looking like a summit to negotiate SALT II and any sort of further arms reductions would not take place until near the 1976 elections, if at all.

It would take a dramatic action to resolve the stalemate. Whom would be the one to provide it?

*****

There were a number of perks to being President, and very few of them ranked higher than the ability to be able to go to any sporting event (with warning, of course) that one wanted. For John Connally, this meant returning home to Texas for Thanksgiving and sitting in a suite at Texas Stadium in Irving, getting to watch his beloved Cowboys battle the Washington Redskins on national television. Yes, Houston had a team, but since the NFL-AFL merger, garbage was a kind word to describe the Oilers, and Connally had no desire to cheer for losers. The Cowboys, they were a winning team, having won Super Bowl VI three years prior. When the press asked during his weekly availability, he’d given the same answer: he was drawn to winners. He then turned to Marvin Kalb standing by his side and whispered, “Bush likes the Oilers because they make him look like a winner by comparison.” Kalb suppressed a chuckle. He didn’t understand why Connally hated a man who lit his political career on fire in front of the media last spring, yet the jokes about Bush usually were pretty funny.

On the flight down, Connally had gone to the back of Air Force One where the press pool sat. He had cash in hand, and asked the reporters if they wanted to place bets on the game. The men were delighted to be part of this quasi-forbidden activity. Gambling on Air Force One with the President! Wallets came out, five bucks per man thrown in the pot, with Marvin Kalb the designated bookie, his little notepad used to designate which team each man chose. The Redskins were neck and neck with the St. Louis Cardinals for first place in the NFC East while the Cowboys trailed two games back, and the pool reporters were mainly Washington residents, so they stuck with the hometown team. Helen Thomas looked at her colleagues and muttered something about objectivity.

The plane landed at Dallas’ Love Field, the same place where Connally had greeted JFK eleven years and six days ago. Despite his excitement for the game, the President couldn’t help but feel a chill when he walked down the steps to the tarmac. This time it was Governor Dolph Briscoe there to greet him, a rancher and former LBJ mentee who’d run on reform and beat Connally’s chief of staff Ben Barnes in the 1972 gubernatorial primary. Briscoe won narrowly that year, but was coming off a smashing reelection win, the first four-year term a Texas governor had been elected to after a recent change to state law. He greeted Connally with the sort of warmth one reserves for a relative that hasn’t been on great terms with the rest of the family. Connally was effusive, feeling the political winds at his back after salvaging what could have been a far more devastating midterm, and brushed off the undertone of Briscoe’s words. It was politics, not personal, and they were both Lyndon’s disciples.

The two rode together in the presidential limousine, as Briscoe marveled at the technology inside of it and they chatted about Dallas’ chances at making the playoffs and marveling at Calvin Hill’s ability off and on the field. Hill was Black, a Yale graduate and a star running back headed for his third straight Pro Bowl appearance. He’d been drafted by the World Football League that year, but chose to stay in Dallas in hopes of another Super Bowl ring. The last two years had seen the Cowboys losing in the NFC championship game, and while they desperately wanted a return to glory, the year had been difficult, starting 2-3 and coming into this game at 7-4, having lost to Washington in the nation’s capital right after the midterms. A win would give the Cowboys a chance to catch the Redskins and win the division, a loss would put them out of contention. There were three games left that season, and this would have the nation’s eyes on it.

On the third drive of the first quarter, Roger Staubach, the Lone Star of the Cowboys, its physical and emotional head, was knocked out of the game after a vicious hit concussed him. The Redskins had openly spoke of their desire to not just stop Staubach, but to hurt him, and they’d gone and achieved it. Staubach’s backup was a shaggy-haired kid from Abilene named Clint Longley, and the Redskins were talking trash and giddy at the possibility of running this kid into the ground. Unbeknownst to them, Longley had improved his accuracy dramatically since training camp (he’d been called the Mad Bomber and missed an out route so badly that his throw, instead of finding Drew Pearson’s hands, knocked Tom Landry’s famed fedora off his head), and the offensive line knew they had to protect him at all costs, or it’d be the first time they missed the playoffs in years.

Longley’s first drive was in the second quarter, down 10-0, and he took the Cowboys down the field behind Hill’s excellent running and a couple of great throws on 3rd and long situations, culminating in a touchdown pass to Golden Richards on a 27-yard post route off of playaction that the Redskins safety had bit hard on. Washington got another field goal on the following possession, but after Richards had returned the ensuing kickoff to the Dallas forty-yard line, offensive coordinator Jim Myers decided to cook up a flea flicker, counterintuitively thinking that Washington wouldn’t expect another run fake right after the last touchdown. Fullback Walt Garrison took the handoff as if to run off-tackle to the right but then pitched it back to Longley (an unconventional style flea flicker that required timing to pull off). Had it gone wrong, it might’ve been the game, but it went very right, and Drew Pearson, who’d started running in as if to throw a block for Garrison, cut sharply right and ran a corner route, catching Longley’s sideline bomb in stride and practically glided into the end zone. The Washington sideline’s faces told the tale. It was game on now, and the Cowboys were up 14-13.

With the shock plays out of the way, Washington’s defensive coordinator decided to try and give Deacon Jones, in his 13th and final season in the NFL, the chance to hit Longley a few times. Jones had been a feared defensive end, innovator of the head slap on offensive lineman to throw them off and get a bead on the quarterback, but was slowed by the toll of his many years of football. Even so, that beast was still inside him, and he was capable of putting the fear of God into a quarterback even at this late stage of his career. A blitz package was drawn up that included a stunt move for Jones, and he took advantage, laying a hit on Longley as he threw the ball away. Several plays later, another, different looking blitz, and Jones caught Longley focusing too much on his receiver and ended the Dallas drive with a sack.

The game, predictably, slowed down, as two of the all-time coaching greats, Tom Landry for Dallas and George Allen for Washington, matched wits and plays. A late third quarter drive would be shut down when Jones hit Longley mid-throw again, causing the pass to flutter and be intercepted by Pro Bowl safety Ken Houston, who got a couple of blocks and returned it for a touchdown. The teams traded field goals to start the fourth quarter, leaving the score at 23-17 in favor of Washington. With their season on the line, the Cowboys managed to stop Washington from converting a 4th and 1 at Dallas’s 38-yard line that would’ve sealed the game. The clock stopped with the turnover on downs, and in the next minute, Clint Longley would enter the history books. He completed an out route to Richards for 12 yards and a first down. He completed an in/out route to Pearson for another first down, the clock stopping each time as the receivers were driven out of bounds. Finally, with 17 seconds on the clock and the ball on the Redskins 23-yard line, Longley dropped back in shotgun, feinted to Pearson running a corner route, and then hit veteran Bob Hayes on a slant route in the end zone to tie the game at 23. The extra point was good, and the Redskins did not have the time left to do anything. Longley had saved the game for his team, and with a long layoff before the next game, Staubach would be back by then, and Longley would take a back seat, his mind swimming with reasons why he should remain THE quarterback in Dallas.

Up in the presidential suite, Connally and Briscoe were whooping it up and bear-hugging their aides. Nothing was transacted that day, but Connally had mended fences with the Democratic governor of his home state, and that was no small feat. The President raised a final glass of bourbon. “Until we meet again at the Super Bowl!” Everyone toasted and then Connally was headed down to the locker room to meet the Mad Bomber. He shook the hands of every player and coach in the room, took grinning photos with Longley that would plaster the Dallas newspapers the next day, and then his motorcade set off back to Love Field, where Air Force One readied itself for the short flight south to San Antonio and the Connally ranch, where the household staff had set out a feast fit for a king, and at this moment, President John Connally felt like one.

*****

Thanksgiving for the Kennedy family was a dour affair, lacking the joy found in Texas. Jackie was very displeased that Ted was running, and told him sternly that he was tempting fate that had been cruel to the family. Her own relationship with the Kennedys had been rocky since her remarriage to Aristotle Onassis in 1968. That marriage itself had been faltering over the past year as Onassis’s own health had declined sharply following the death of his son in a plane crash. He’d become very withdrawn, and Jackie again felt the pain of marital neglect. His doctors were certain it’d be his last Christmas, and Jackie understood inside that if she didn’t mend fences here, she’d have no family to turn to afterwards when Aristotle died. Ethel tried to put on a good front, but her fears were even more consuming, with Bobby’s death being much more recent, and so she looked at Ted with watery, pleading eyes while Jackie’s cold voice lit into him. Joan was struggling to stay sober as the stress of a job she did not want and a marriage that had been rocky at best since Chappaquiddick was eating at her. The drugs that her doctor gave her left her unable to function intelligently, and because speaking publicly was a political wife’s job, she had to skip them on the days she craved their release the most. Today, she’d taken half a dose, just enough to keep the edge off of her anxiety so she wouldn’t start chugging vodka.

Rose, the fierce matriarch, was the only one to offer Ted support, and she archly suggested that the wives were acting like the real turkeys. The kids helped liven things up, as kids are wont to do, and this family had an abundance of them. Caroline was a lively teenager with auburn hair and a Kennedyesque smile, one reminiscent of her murdered Uncle Bobby; John Jr growing into a distinctly Bouvier face with the build of a Kennedy; the newly married Kathleen, Bobby’s oldest; Joseph P. Kennedy II (technically the third); Bobby Jr., David, Courtney, Michael, Kerry, Chris (literally born on the Fourth of July, 1963), Max, Douglas, and finally Rory, who was in utero when her father was murdered. Then there was Ted’s kids, his eldest daughter, Kara; Ted Jr., who’d survived bone cancer; and Patrick, his youngest, the most Irish looking of them all with his shock of fierce red hair, just like his namesake, the patriarch of the Kennedys in America.

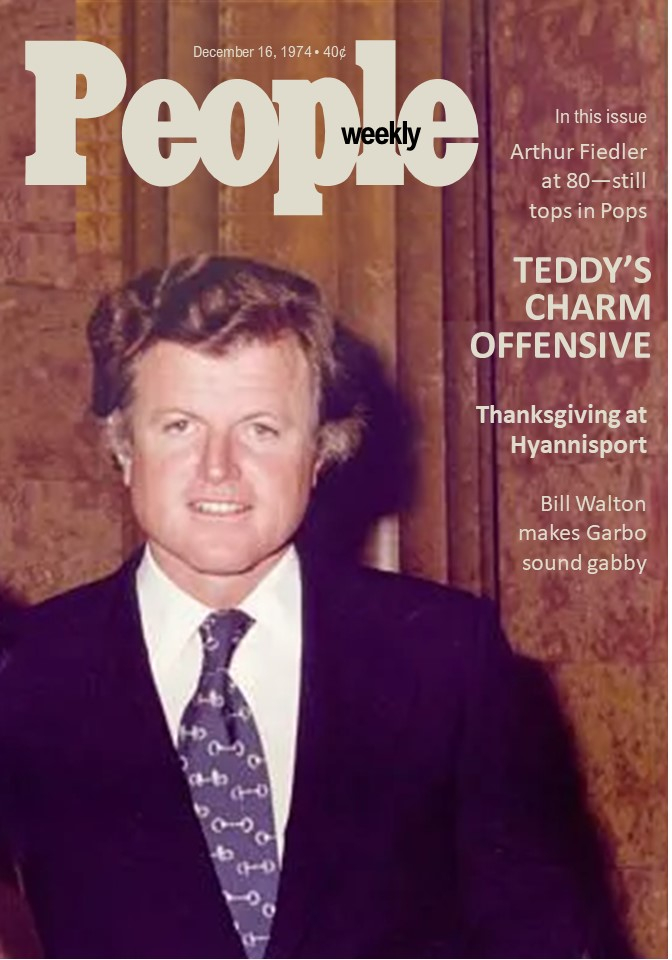

So many kids helped give off the air of a royal family, even after Jack and Bobby’s deaths. While America’s media had become far more cynical in the post-Nixon era, magazines like People Weekly loved glossy stories, and the Kennedys were very glossy indeed. A photographer and reporter were there, observing at a distance, in the sort of PR stunt that Joe Senior had been excellent at conjuring up for his family. As it was considered far too early to officially campaign, Ted’s goal was to burnish his family credentials and further push Chappaquiddick to the back burner. The five-year anniversary in July had been brutal for everyone involved, almost caused Joan and he to fall off the wagon, an upsurge in interest in the case and not his candidacy, a reminder of the worst night of his life. That was all before the Kopechnes used the opportunity to say they thought he should never be President. He needed positive coverage, and so People was here to take it in, except that Jackie was scolding him for running while Ethel was on the verge of bursting into tears! Can’t they see that I need to do this, that John Connally is an oil salesman who was in the car with Jack, got shot himself, and still turned his back on the common man? I’m the only person who can stand up against John Connally. Nobody else has the connection to that day. I’m the one who has to take him on and beat him.

The general public is often dismissive of “gossip” reporters who cover parties and celebrities, but in some ways, they’re the sharpest ones out there, because they always listen. Most of their work does not come from documents or other tangible items, but purely from words and observations. The reporter sent out by People Weekly was a young woman who’d been working at Time magazine in the “People” section, which was spun out into the magazine, and the editorial staff were all Time/Life veterans, which gave People Weekly an edge that most of its story subjects failed to consider throughout its inaugural year. The reporter was named Megan Browne, and she’d done her best impression of a statue in the back of the room when the bickering was taking place, memorizing it, and after some time passed, Ms. Browne excused herself to the restroom and began writing in her small reporter’s notebook everything she’d heard at the table. When the story ran two weeks later in the December 16th issue, the glossy photo spread could not obscure the news in there that the Kennedy widows were not behind a third candidacy for President. It was another blow that made the youngest Kennedy brother look like an amateur, an impression he had to shake if he was to have any chance of winning.

It would take a dramatic action to resolve the stalemate. Whom would be the one to provide it?

*****

There were a number of perks to being President, and very few of them ranked higher than the ability to be able to go to any sporting event (with warning, of course) that one wanted. For John Connally, this meant returning home to Texas for Thanksgiving and sitting in a suite at Texas Stadium in Irving, getting to watch his beloved Cowboys battle the Washington Redskins on national television. Yes, Houston had a team, but since the NFL-AFL merger, garbage was a kind word to describe the Oilers, and Connally had no desire to cheer for losers. The Cowboys, they were a winning team, having won Super Bowl VI three years prior. When the press asked during his weekly availability, he’d given the same answer: he was drawn to winners. He then turned to Marvin Kalb standing by his side and whispered, “Bush likes the Oilers because they make him look like a winner by comparison.” Kalb suppressed a chuckle. He didn’t understand why Connally hated a man who lit his political career on fire in front of the media last spring, yet the jokes about Bush usually were pretty funny.

On the flight down, Connally had gone to the back of Air Force One where the press pool sat. He had cash in hand, and asked the reporters if they wanted to place bets on the game. The men were delighted to be part of this quasi-forbidden activity. Gambling on Air Force One with the President! Wallets came out, five bucks per man thrown in the pot, with Marvin Kalb the designated bookie, his little notepad used to designate which team each man chose. The Redskins were neck and neck with the St. Louis Cardinals for first place in the NFC East while the Cowboys trailed two games back, and the pool reporters were mainly Washington residents, so they stuck with the hometown team. Helen Thomas looked at her colleagues and muttered something about objectivity.

The plane landed at Dallas’ Love Field, the same place where Connally had greeted JFK eleven years and six days ago. Despite his excitement for the game, the President couldn’t help but feel a chill when he walked down the steps to the tarmac. This time it was Governor Dolph Briscoe there to greet him, a rancher and former LBJ mentee who’d run on reform and beat Connally’s chief of staff Ben Barnes in the 1972 gubernatorial primary. Briscoe won narrowly that year, but was coming off a smashing reelection win, the first four-year term a Texas governor had been elected to after a recent change to state law. He greeted Connally with the sort of warmth one reserves for a relative that hasn’t been on great terms with the rest of the family. Connally was effusive, feeling the political winds at his back after salvaging what could have been a far more devastating midterm, and brushed off the undertone of Briscoe’s words. It was politics, not personal, and they were both Lyndon’s disciples.

The two rode together in the presidential limousine, as Briscoe marveled at the technology inside of it and they chatted about Dallas’ chances at making the playoffs and marveling at Calvin Hill’s ability off and on the field. Hill was Black, a Yale graduate and a star running back headed for his third straight Pro Bowl appearance. He’d been drafted by the World Football League that year, but chose to stay in Dallas in hopes of another Super Bowl ring. The last two years had seen the Cowboys losing in the NFC championship game, and while they desperately wanted a return to glory, the year had been difficult, starting 2-3 and coming into this game at 7-4, having lost to Washington in the nation’s capital right after the midterms. A win would give the Cowboys a chance to catch the Redskins and win the division, a loss would put them out of contention. There were three games left that season, and this would have the nation’s eyes on it.

On the third drive of the first quarter, Roger Staubach, the Lone Star of the Cowboys, its physical and emotional head, was knocked out of the game after a vicious hit concussed him. The Redskins had openly spoke of their desire to not just stop Staubach, but to hurt him, and they’d gone and achieved it. Staubach’s backup was a shaggy-haired kid from Abilene named Clint Longley, and the Redskins were talking trash and giddy at the possibility of running this kid into the ground. Unbeknownst to them, Longley had improved his accuracy dramatically since training camp (he’d been called the Mad Bomber and missed an out route so badly that his throw, instead of finding Drew Pearson’s hands, knocked Tom Landry’s famed fedora off his head), and the offensive line knew they had to protect him at all costs, or it’d be the first time they missed the playoffs in years.

Longley’s first drive was in the second quarter, down 10-0, and he took the Cowboys down the field behind Hill’s excellent running and a couple of great throws on 3rd and long situations, culminating in a touchdown pass to Golden Richards on a 27-yard post route off of playaction that the Redskins safety had bit hard on. Washington got another field goal on the following possession, but after Richards had returned the ensuing kickoff to the Dallas forty-yard line, offensive coordinator Jim Myers decided to cook up a flea flicker, counterintuitively thinking that Washington wouldn’t expect another run fake right after the last touchdown. Fullback Walt Garrison took the handoff as if to run off-tackle to the right but then pitched it back to Longley (an unconventional style flea flicker that required timing to pull off). Had it gone wrong, it might’ve been the game, but it went very right, and Drew Pearson, who’d started running in as if to throw a block for Garrison, cut sharply right and ran a corner route, catching Longley’s sideline bomb in stride and practically glided into the end zone. The Washington sideline’s faces told the tale. It was game on now, and the Cowboys were up 14-13.

With the shock plays out of the way, Washington’s defensive coordinator decided to try and give Deacon Jones, in his 13th and final season in the NFL, the chance to hit Longley a few times. Jones had been a feared defensive end, innovator of the head slap on offensive lineman to throw them off and get a bead on the quarterback, but was slowed by the toll of his many years of football. Even so, that beast was still inside him, and he was capable of putting the fear of God into a quarterback even at this late stage of his career. A blitz package was drawn up that included a stunt move for Jones, and he took advantage, laying a hit on Longley as he threw the ball away. Several plays later, another, different looking blitz, and Jones caught Longley focusing too much on his receiver and ended the Dallas drive with a sack.

The game, predictably, slowed down, as two of the all-time coaching greats, Tom Landry for Dallas and George Allen for Washington, matched wits and plays. A late third quarter drive would be shut down when Jones hit Longley mid-throw again, causing the pass to flutter and be intercepted by Pro Bowl safety Ken Houston, who got a couple of blocks and returned it for a touchdown. The teams traded field goals to start the fourth quarter, leaving the score at 23-17 in favor of Washington. With their season on the line, the Cowboys managed to stop Washington from converting a 4th and 1 at Dallas’s 38-yard line that would’ve sealed the game. The clock stopped with the turnover on downs, and in the next minute, Clint Longley would enter the history books. He completed an out route to Richards for 12 yards and a first down. He completed an in/out route to Pearson for another first down, the clock stopping each time as the receivers were driven out of bounds. Finally, with 17 seconds on the clock and the ball on the Redskins 23-yard line, Longley dropped back in shotgun, feinted to Pearson running a corner route, and then hit veteran Bob Hayes on a slant route in the end zone to tie the game at 23. The extra point was good, and the Redskins did not have the time left to do anything. Longley had saved the game for his team, and with a long layoff before the next game, Staubach would be back by then, and Longley would take a back seat, his mind swimming with reasons why he should remain THE quarterback in Dallas.

Up in the presidential suite, Connally and Briscoe were whooping it up and bear-hugging their aides. Nothing was transacted that day, but Connally had mended fences with the Democratic governor of his home state, and that was no small feat. The President raised a final glass of bourbon. “Until we meet again at the Super Bowl!” Everyone toasted and then Connally was headed down to the locker room to meet the Mad Bomber. He shook the hands of every player and coach in the room, took grinning photos with Longley that would plaster the Dallas newspapers the next day, and then his motorcade set off back to Love Field, where Air Force One readied itself for the short flight south to San Antonio and the Connally ranch, where the household staff had set out a feast fit for a king, and at this moment, President John Connally felt like one.

*****

Thanksgiving for the Kennedy family was a dour affair, lacking the joy found in Texas. Jackie was very displeased that Ted was running, and told him sternly that he was tempting fate that had been cruel to the family. Her own relationship with the Kennedys had been rocky since her remarriage to Aristotle Onassis in 1968. That marriage itself had been faltering over the past year as Onassis’s own health had declined sharply following the death of his son in a plane crash. He’d become very withdrawn, and Jackie again felt the pain of marital neglect. His doctors were certain it’d be his last Christmas, and Jackie understood inside that if she didn’t mend fences here, she’d have no family to turn to afterwards when Aristotle died. Ethel tried to put on a good front, but her fears were even more consuming, with Bobby’s death being much more recent, and so she looked at Ted with watery, pleading eyes while Jackie’s cold voice lit into him. Joan was struggling to stay sober as the stress of a job she did not want and a marriage that had been rocky at best since Chappaquiddick was eating at her. The drugs that her doctor gave her left her unable to function intelligently, and because speaking publicly was a political wife’s job, she had to skip them on the days she craved their release the most. Today, she’d taken half a dose, just enough to keep the edge off of her anxiety so she wouldn’t start chugging vodka.

Rose, the fierce matriarch, was the only one to offer Ted support, and she archly suggested that the wives were acting like the real turkeys. The kids helped liven things up, as kids are wont to do, and this family had an abundance of them. Caroline was a lively teenager with auburn hair and a Kennedyesque smile, one reminiscent of her murdered Uncle Bobby; John Jr growing into a distinctly Bouvier face with the build of a Kennedy; the newly married Kathleen, Bobby’s oldest; Joseph P. Kennedy II (technically the third); Bobby Jr., David, Courtney, Michael, Kerry, Chris (literally born on the Fourth of July, 1963), Max, Douglas, and finally Rory, who was in utero when her father was murdered. Then there was Ted’s kids, his eldest daughter, Kara; Ted Jr., who’d survived bone cancer; and Patrick, his youngest, the most Irish looking of them all with his shock of fierce red hair, just like his namesake, the patriarch of the Kennedys in America.

So many kids helped give off the air of a royal family, even after Jack and Bobby’s deaths. While America’s media had become far more cynical in the post-Nixon era, magazines like People Weekly loved glossy stories, and the Kennedys were very glossy indeed. A photographer and reporter were there, observing at a distance, in the sort of PR stunt that Joe Senior had been excellent at conjuring up for his family. As it was considered far too early to officially campaign, Ted’s goal was to burnish his family credentials and further push Chappaquiddick to the back burner. The five-year anniversary in July had been brutal for everyone involved, almost caused Joan and he to fall off the wagon, an upsurge in interest in the case and not his candidacy, a reminder of the worst night of his life. That was all before the Kopechnes used the opportunity to say they thought he should never be President. He needed positive coverage, and so People was here to take it in, except that Jackie was scolding him for running while Ethel was on the verge of bursting into tears! Can’t they see that I need to do this, that John Connally is an oil salesman who was in the car with Jack, got shot himself, and still turned his back on the common man? I’m the only person who can stand up against John Connally. Nobody else has the connection to that day. I’m the one who has to take him on and beat him.

The general public is often dismissive of “gossip” reporters who cover parties and celebrities, but in some ways, they’re the sharpest ones out there, because they always listen. Most of their work does not come from documents or other tangible items, but purely from words and observations. The reporter sent out by People Weekly was a young woman who’d been working at Time magazine in the “People” section, which was spun out into the magazine, and the editorial staff were all Time/Life veterans, which gave People Weekly an edge that most of its story subjects failed to consider throughout its inaugural year. The reporter was named Megan Browne, and she’d done her best impression of a statue in the back of the room when the bickering was taking place, memorizing it, and after some time passed, Ms. Browne excused herself to the restroom and began writing in her small reporter’s notebook everything she’d heard at the table. When the story ran two weeks later in the December 16th issue, the glossy photo spread could not obscure the news in there that the Kennedy widows were not behind a third candidacy for President. It was another blow that made the youngest Kennedy brother look like an amateur, an impression he had to shake if he was to have any chance of winning.

Last edited:

Great update! It's been a while since the last one but this one feels like a beat hasn't been missed. Glad you're back at it after a hard time.

What I like about Big Bad John is he knows how to have fun and he seems enjoy other people having a good time with him. Unless he hates them.

Oh Teddy, we know Connally is going to win in 76, don't burn yourself down trying to run.

The Soviet portion was short but damn was it intriguing. I hope Kosygin makes the right moves.

What I like about Big Bad John is he knows how to have fun and he seems enjoy other people having a good time with him. Unless he hates them.

Oh Teddy, we know Connally is going to win in 76, don't burn yourself down trying to run.

The Soviet portion was short but damn was it intriguing. I hope Kosygin makes the right moves.

Ah, I'd almost forgotten about Clint Longley. He took the goodwill from leading the Cowboys past the Redskins on Thanksgiving--Thanksgiving!--and proceeded to throw it all away when he decided to settle a dispute with Roger Staubach, the starting QB of the Cowboys and one of the most beloved Cowboy players in the nation, IMO, by sucker-punching him, which is, really, really dumb (1). Yeah, there's a reason why the Cowboys decided to go with Danny White as backup QB when he became available, and White was a decent QB in his own right (2), IMO.

Nice to see John having fun here, though, and a good update; hope your other TL is updated soon...

(1) For one thing, it turned the Cowboys fanbase and team against him and, second, he's lucky Staubach held back--Staubach had served in Vietnam before joining the Cowboys (he had been the Navy QB--he was nicknamed Captain America for this reason) and could have put him in the hospital if he wanted to.

(2) He led the Cowboys to three straight NFC title games in the early 1980s, losing to the Super Bowl runner-up (the Cowboys' division rivals, the Philadelphia Eagles) in the 1980 season, and the eventual winner in the 1981 and 1982 seasons; the closest he came was in the 1981 NFC title game against the 49ers, where many people remember The Catch, but not many people remember that White had thrown a pass to Drew Pearson that would have been a TD if San Francisco 49ers cornerback Eric Wright (a good player for the 49ers defense alongside Ronnie Lott, IMO) hadn't made a horse-collar tackle of him (3) and helped preserve the 49ers win.

(3) The horse-collar tackle wouldn't be a penalty until after Dallas Cowboys safety Roy Williams, of all people, injured several players with the tackle in the 2004 season, including Terrell Owens--who, funnily enough, became Williams' teammate when he joined the Cowboys in 2006...

Nice to see John having fun here, though, and a good update; hope your other TL is updated soon...

(1) For one thing, it turned the Cowboys fanbase and team against him and, second, he's lucky Staubach held back--Staubach had served in Vietnam before joining the Cowboys (he had been the Navy QB--he was nicknamed Captain America for this reason) and could have put him in the hospital if he wanted to.

(2) He led the Cowboys to three straight NFC title games in the early 1980s, losing to the Super Bowl runner-up (the Cowboys' division rivals, the Philadelphia Eagles) in the 1980 season, and the eventual winner in the 1981 and 1982 seasons; the closest he came was in the 1981 NFC title game against the 49ers, where many people remember The Catch, but not many people remember that White had thrown a pass to Drew Pearson that would have been a TD if San Francisco 49ers cornerback Eric Wright (a good player for the 49ers defense alongside Ronnie Lott, IMO) hadn't made a horse-collar tackle of him (3) and helped preserve the 49ers win.

(3) The horse-collar tackle wouldn't be a penalty until after Dallas Cowboys safety Roy Williams, of all people, injured several players with the tackle in the 2004 season, including Terrell Owens--who, funnily enough, became Williams' teammate when he joined the Cowboys in 2006...

May your mom rest in peace. I really hope you'll find energy and joy not only to keep on working on this amazing tale you created, but to keep on living, working, and being the great family man and person I'm absolutely sure you are. May God be with you.

So glad you are back. Can easily picture the Hiannius Port crowd in conclaveIt had been surprising, really, the Central Committee man thought as the Politburo members trudged out of their meeting. Their inability to pick a successor to old Leonid has created true collective rule, and collective rule could better be defined as paralysis. The belief that Yuri Andropov would just slide into Brezhnev’s warm chair was upended by the Korean misadventure. Tensions continued to remain high, but at least nobody was actively shooting at each other. Regardless, it was enough to where a faction under Kosygin had managed to prevent Andropov’s ascension—it was an unwritten but hard rule that votes had to be unanimous when it involved the promotion to the Politburo or a secretariat position. Right now, Andropov held a majority, but it wasn’t even close to a majority where he’d feel comfortable calling a vote. Kosygin might’ve been marginalized by Brezhnev, but he still held a lot of power, whereas Andropov had only been a full member of the Politburo since 1971. Both men were now jockeying for position with their colleagues while showing the world a united front—except that it was increasingly looking like a summit to negotiate SALT II and any sort of further arms reductions would not take place until near the 1976 elections, if at all.

It would take a dramatic action to resolve the stalemate. Whom would be the one to provide it?

*****

There were a number of perks to being President, and very few of them ranked higher than the ability to be able to go to any sporting event (with warning, of course) that one wanted. For John Connally, this meant returning home to Texas for Thanksgiving and sitting in a suite at Texas Stadium in Irving, getting to watch his beloved Cowboys battle the Washington Redskins on national television. Yes, Houston had a team, but since the NFL-AFL merger, garbage was a kind word to describe the Oilers, and Connally had no desire to cheer for losers. The Cowboys, they were a winning team, having won Super Bowl VI three years prior. When the press asked during his weekly availability, he’d given the same answer: he was drawn to winners. He then turned to Marvin Kalb standing by his side and whispered, “Bush likes the Oilers because they make him look like a winner by comparison.” Kalb suppressed a chuckle. He didn’t understand why Connally hated a man who lit his political career on fire in front of the media last spring, yet the jokes about Bush usually were pretty funny.

On the flight down, Connally had gone to the back of Air Force One where the press pool sat. He had cash in hand, and asked the reporters if they wanted to place bets on the game. The men were delighted to be part of this quasi-forbidden activity. Gambling on Air Force One with the President! Wallets came out, five bucks per man thrown in the pot, with Marvin Kalb the designated bookie, his little notepad used to designate which team each man chose. The Redskins were neck and neck with the St. Louis Cardinals for first place in the NFC East while the Cowboys trailed two games back, and the pool reporters were mainly Washington residents, so they stuck with the hometown team. Helen Thomas looked at her colleagues and muttered something about objectivity.

The plane landed at Dallas’ Love Field, the same place where Connally had greeted JFK eleven years and six days ago. Despite his excitement for the game, the President couldn’t help but feel a chill when he walked down the steps to the tarmac. This time it was Governor Dolph Briscoe there to greet him, a rancher and former LBJ mentee who’d run on reform and beat Connally’s chief of staff Ben Barnes in the 1972 gubernatorial primary. Briscoe won narrowly that year, but was coming off a smashing reelection win, the first four-year term a Texas governor had been elected to after a recent change to state law. He greeted Connally with the sort of warmth one reserves for a relative that hasn’t been on great terms with the rest of the family. Connally was effusive, feeling the political winds at his back after salvaging what could have been a far more devastating midterm, and brushed off the undertone of Briscoe’s words. It was politics, not personal, and they were both Lyndon’s disciples.

The two rode together in the presidential limousine, as Briscoe marveled at the technology inside of it and they chatted about Dallas’ chances at making the playoffs and marveling at Calvin Hill’s ability off and on the field. Hill was Black, a Yale graduate and a star running back headed for his third straight Pro Bowl appearance. He’d been drafted by the World Football League that year, but chose to stay in Dallas in hopes of another Super Bowl ring. The last two years had seen the Cowboys losing in the NFC championship game, and while they desperately wanted a return to glory, the year had been difficult, starting 2-3 and coming into this game at 7-4, having lost to Washington in the nation’s capital right after the midterms. A win would give the Cowboys a chance to catch the Redskins and win the division, a loss would put them out of contention. There were three games left that season, and this would have the nation’s eyes on it.

On the third drive of the first quarter, Roger Staubach, the Lone Star of the Cowboys, its physical and emotional head, was knocked out of the game after a vicious hit concussed him. The Redskins had openly spoke of their desire to not just stop Staubach, but to hurt him, and they’d gone and achieved it. Staubach’s backup was a shaggy-haired kid from Abilene named Clint Longley, and the Redskins were talking trash and giddy at the possibility of running this kid into the ground. Unbeknownst to them, Longley had improved his accuracy dramatically since training camp (he’d been called the Mad Bomber and missed an out route so badly that his throw, instead of finding Drew Pearson’s hands, knocked Tom Landry’s famed fedora off his head), and the offensive line knew they had to protect him at all costs, or it’d be the first time they missed the playoffs in years.

Longley’s first drive was in the second quarter, down 10-0, and he took the Cowboys down the field behind Hill’s excellent running and a couple of great throws on 3rd and long situations, culminating in a touchdown pass to Golden Richards on a 27-yard post route off of playaction that the Redskins safety had bit hard on. Washington got another field goal on the following possession, but after Richards had returned the ensuing kickoff to the Dallas forty-yard line, offensive coordinator Jim Myers decided to cook up a flea flicker, counterintuitively thinking that Washington wouldn’t expect another run fake right after the last touchdown. Fullback Walt Garrison took the handoff as if to run off-tackle to the right but then pitched it back to Longley (an unconventional style flea flicker that required timing to pull off). Had it gone wrong, it might’ve been the game, but it went very right, and Drew Pearson, who’d started running in as if to throw a block for Garrison, cut sharply right and ran a corner route, catching Longley’s sideline bomb in stride and practically glided into the end zone. The Washington sideline’s faces told the tale. It was game on now, and the Cowboys were up 14-13.

With the shock plays out of the way, Washington’s defensive coordinator decided to try and give Deacon Jones, in his 13th and final season in the NFL, the chance to hit Longley a few times. Jones had been a feared defensive end, innovator of the head slap on offensive lineman to throw them off and get a bead on the quarterback, but was slowed by the toll of his many years of football. Even so, that beast was still inside him, and he was capable of putting the fear of God into a quarterback even at this late stage of his career. A blitz package was drawn up that included a stunt move for Jones, and he took advantage, laying a hit on Longley as he threw the ball away. Several plays later, another, different looking blitz, and Jones caught Longley focusing too much on his receiver and ended the Dallas drive with a sack.

The game, predictably, slowed down, as two of the all-time coaching greats, Tom Landry for Dallas and George Allen for Washington, matched wits and plays. A late third quarter drive would be shut down when Jones hit Longley mid-throw again, causing the pass to flutter and be intercepted by Pro Bowl safety Ken Houston, who got a couple of blocks and returned it for a touchdown. The teams traded field goals to start the fourth quarter, leaving the score at 23-17 in favor of Washington. With their season on the line, the Cowboys managed to stop Washington from converting a 4th and 1 at Dallas’s 38-yard line that would’ve sealed the game. The clock stopped with the turnover on downs, and in the next minute, Clint Longley would enter the history books. He completed an out route to Richards for 12 yards and a first down. He completed an in/out route to Pearson for another first down, the clock stopping each time as the receivers were driven out of bounds. Finally, with 17 seconds on the clock and the ball on the Redskins 23-yard line, Longley dropped back in shotgun, feinted to Pearson running a corner route, and then hit veteran Bob Hayes on a slant route in the end zone to tie the game at 23. The extra point was good, and the Redskins did not have the time left to do anything. Longley had saved the game for his team, and with a long layoff before the next game, Staubach would be back by then, and Longley would take a back seat, his mind swimming with reasons why he should remain THE quarterback in Dallas.

Up in the presidential suite, Connally and Briscoe were whooping it up and bear-hugging their aides. Nothing was transacted that day, but Connally had mended fences with the Democratic governor of his home state, and that was no small feat. The President raised a final glass of bourbon. “Until we meet again at the Super Bowl!” Everyone toasted and then Connally was headed down to the locker room to meet the Mad Bomber. He shook the hands of every player and coach in the room, took grinning photos with Longley that would plaster the Dallas newspapers the next day, and then his motorcade set off back to Love Field, where Air Force One readied itself for the short flight south to San Antonio and the Connally ranch, where the household staff had set out a feast fit for a king, and at this moment, President John Connally felt like one.

*****

Thanksgiving for the Kennedy family was a dour affair, lacking the joy found in Texas. Jackie was very displeased that Ted was running, and told him sternly that he was tempting fate that had been cruel to the family. Her own relationship with the Kennedys had been rocky since her remarriage to Aristotle Onassis in 1968. That marriage itself had been faltering over the past year as Onassis’s own health had declined sharply following the death of his son in a plane crash. He’d become very withdrawn, and Jackie again felt the pain of marital neglect. His doctors were certain it’d be his last Christmas, and Jackie understood inside that if she didn’t mend fences here, she’d have no family to turn to afterwards when Aristotle died. Ethel tried to put on a good front, but her fears were even more consuming, with Bobby’s death being much more recent, and so she looked at Ted with watery, pleading eyes while Jackie’s cold voice lit into him. Joan was struggling to stay sober as the stress of a job she did not want and a marriage that had been rocky at best since Chappaquiddick was eating at her. The drugs that her doctor gave her left her unable to function intelligently, and because speaking publicly was a political wife’s job, she had to skip them on the days she craved their release the most. Today, she’d taken half a dose, just enough to keep the edge off of her anxiety so she wouldn’t start chugging vodka.

Rose, the fierce matriarch, was the only one to offer Ted support, and she archly suggested that the wives were acting like the real turkeys. The kids helped liven things up, as kids are wont to do, and this family had an abundance of them. Caroline was a lively teenager with auburn hair and a Kennedyesque smile, one reminiscent of her murdered Uncle Bobby; John Jr growing into a distinctly Bouvier face with the build of a Kennedy; the newly married Kathleen, Bobby’s oldest; Joseph P. Kennedy II (technically the third); Bobby Jr., David, Courtney, Michael, Kerry, Chris (literally born on the Fourth of July, 1963), Max, Douglas, and finally Rory, who was in utero when her father was murdered. Then there was Ted’s kids, his eldest daughter, Kara; Ted Jr., who’d survived bone cancer; and Patrick, his youngest, the most Irish looking of them all with his shock of fierce red hair, just like his namesake, the patriarch of the Kennedys in America.

So many kids helped give off the air of a royal family, even after Jack and Bobby’s deaths. While America’s media had become far more cynical in the post-Nixon era, magazines like People Weekly loved glossy stories, and the Kennedys were very glossy indeed. A photographer and reporter were there, observing at a distance, in the sort of PR stunt that Joe Senior had been excellent at conjuring up for his family. As it was considered far too early to officially campaign, Ted’s goal was to burnish his family credentials and further push Chappaquiddick to the back burner. The five-year anniversary in July had been brutal for everyone involved, almost caused Joan and he to fall off the wagon, an upsurge in interest in the case and not his candidacy, a reminder of the worst night of his life. That was all before the Kopechnes used the opportunity to say they thought he should never be President. He needed positive coverage, and so People was here to take it in, except that Jackie was scolding him for running while Ethel was on the verge of bursting into tears! Can’t they see that I need to do this, that John Connally is an oil salesman who was in the car with Jack, got shot himself, and still turned his back on the common man? I’m the only person who can stand up against John Connally. Nobody else has the connection to that day. I’m the one who has to take him on and beat him.

The general public is often dismissive of “gossip” reporters who cover parties and celebrities, but in some ways, they’re the sharpest ones out there, because they always listen. Most of their work does not come from documents or other tangible items, but purely from words and observations. The reporter sent out by People Weekly was a young woman who’d been working at Time magazine in the “People” section, which was spun out into the magazine, and the editorial staff were all Time/Life veterans, which gave People Weekly an edge that most of its story subjects failed to consider throughout its inaugural year. The reporter was named Megan Browne, and she’d done her best impression of a statue in the back of the room when the bickering was taking place, memorizing it, and after some time passed, Ms. Browne excused herself to the restroom and began writing in her small reporter’s notebook everything she’d heard at the table. When the story ran two weeks later in the December 16th issue, the glossy photo spread could not obscure the news in there that the Kennedy widows were not behind a third candidacy for President. It was another blow that made the youngest Kennedy brother look like an amateur, an impression he had to shake if he was to have any chance of winning.

View attachment 796341

Glad to have you back. Loved reading this update. Ted I don't think you'll be able to get the nomination in '76. Great job showing Conally having fun with the football team

And I just found out this TL existed. I will watch with great interest!

Is Brezhnev going to kick the bucket, by any chance? One of my favorite (currently on hiatus) TLs had him bite the dust sometime after the stroke but before Afghanistan and had Andropov take over.

Is Brezhnev going to kick the bucket, by any chance? One of my favorite (currently on hiatus) TLs had him bite the dust sometime after the stroke but before Afghanistan and had Andropov take over.

First off, my apologies if it read slightly weird. This is my first time looking at it since I posted it and I realized that the italics had not copied over like they usually do. I've since corrected that.<snip>

Secondly, I am making progress with processing my mother's death. I can't say how evenly things will be written, but I found the ability to write this chapter, which I think is a good start.

Third, no, Leonid Ilych is not dead, but he will be like Ariel Sharon was at the end, so he might as well be.

Finally, fun fact, the other headlines on that issue are from OTL.

P.S. @Vidal Jimmy Two is amazing and very well-written. Your attention to detail is impeccable.

January 3-7, 1975

The 94th Congress was being sworn in today, and for Ted Kennedy it was one of his favorite days. He was still new enough to Congress, in a sense, that he wasn’t yet jaded by the ceremony that swearing-in day brought to Capitol Hill. Entering his 13th year of service in the Senate, he relished the opportunity to push legislation through without much worry about the filibuster. Sixty Democratic senators was a filibuster-proof majority so long as they stuck together, and while that was unlikely in some areas (such as civil rights), in others like health care, opportunity abounded. Ted was quietly considering how to advance the national health insurance plan that Nixon had endorsed in 1971, believing it had a better chance with Connally than most people thought. It helped elevate both men, but for Kennedy, this was about more than helping his presidential prospects. This was his dream, something he’d wanted since he toured the factory floors in western Massachusetts and walked the wharfs in Boston—health insurance not tied to jobs, not reliant upon the whims of an employer but available for every American. It was too much to hope for a National Health Service on the scale of Great Britain’s, at least not yet, but this would be a landmark step. Democrats had overwhelming majorities in both houses, and with Vietnam winding down, the need for such care had become all too obvious: the Veterans Administration, headed by former Congressman Richard Roudebush, was floundering with the weight of so many badly wounded veterans of Vietnam. They couldn’t even begin to cope with the strain of the mental health care needed, something that had not been considered much in prior wars. The rampant drug abuse and homelessness of those who came back shattered from Southeast Asia, mentally, physically, or both, was an urgent priority, one which Kennedy would use as a shoehorn with the Dixiecrats to get his 60 votes.

Best of all for Ted, having cleaned up and gotten sober, Mike Mansfield brought him back into the leadership fold as head of the Senate Democratic Policy Committee. It was Mansfield himself who’d held the position for fourteen years, and he wanted to elevate Ted’s chances in 1976. He would, in consultation with Mansfield and Robert Byrd, determine the legislation Democrats would advance between now and Election Day in 1976. All of these thoughts were running through the mind of the youngest Kennedy as he helped swear in his new colleagues. He had quietly insisted that he get to swear in the new Kansas senator, Dr. Bill Roy, because he wanted the chance to pull him aside and talk about the healthcare bill. Roy had advocated for just such a thing in the House, and as a doctor of renown, would carry weight when he spoke on the matter. Senate tradition had long dictated that you are seen, not heard, for months before you speak on the floor. Ted Kennedy had known and abided by that tradition when he’d joined the Senate, and was determined to shove it into the dustbin of history. That fealty to tradition in the Senate had created Dick Nixon and Lyndon Johnson (Teddy was friends with the deceased ex-President, but not blind to his many faults), and other leaders who’d gone morally and legally astray. Some of them were still in this room: John Stennis, James Eastland, Russell Long, Sam Ervin. Ervin was better than most of them, had definitely mellowed in the last couple of years, but the others were still pieces of work who would raise hell and complain about any subversion of their traditions. No matter. Ted knew how to work with these men, cut deals, charm them. They respected his getting sober, too, and always had some ginger ale ready for him to sip on instead of their bourbon.

A new Congress and new possibilities. Things were looking up in Ted Kennedy’s eyes.

Across the Capitol, in the back rooms of power, matters were less sanguine. Carl Albert, about to begin his fifth year as Speaker of the House, was losing his nerve. Nobody was quite sure when it started, and even Carl himself couldn’t pinpoint a time, but between the impeachment trial and the Korean crisis, the liquor wasn’t cutting it. He began to get the shakes, and while he did his best to conceal it, the whispers had been circulating around the House leadership for a couple of months now. He was not as vibrant, as engaged, as he had been before. No matter how much he’d drank in the past, it hadn’t dulled his ability to engage. Now he couldn’t control his hands and he couldn’t focus while engaged in conversation. He wanted to get through the 1976 elections, wanted to take this new and rambunctious House and guide it to safe shores. Before the swearing-in could take place, the Speaker had to be elected, and Albert had delayed the vote for a few hours. The results of his tests at Walter Reed Medical Center had come back. He had Parkinson’s Disease, and it was accelerating quickly. His cognitive test results showed decline in progress. He might be a nervous alcoholic, but at his core, Carl Albert was a man of honor for whom his oath of office meant something. It was a fairly easy decision when push came to shove. He would not stand for Speaker and would retire at the end of his term. The doctors said that the less stress he had, the slower the Parkinson’s would progress. He could be present, consult, offer guidance to the new members, but not have to bear the burden of running this madhouse. There was one thing he wanted more than anything, and that was to not be humiliated publicly. Any sort of breakdown would be all anyone remembered.

Albert scanned over the results again, sighed, and put the papers down. He tilted his head up at his guests, Majority Leader Tip O’Neill and Majority Whip John McFall. “Tip, I’m standing down, and I’m going to go to the floor and nominate you as the next Speaker. These papers here,” Albert gestured back at the desk, “say I have Parkinson’s and it’s advancing fairly quickly. I can’t stay Speaker. You’re up to bat, Tip, and I know you’re gonna be great at this job. I’ll even leave you a bottle of my best bourbon.” O’Neill chuckled, that deep rumbling Boston baritone that would become very familiar in the coming years to Americans across the country. “Carl, you’ve done a wonderful job and I’ve been proud to serve under you. The way you handled the last two years...few men could’ve done as well.”

Within the hour, a caucus meeting was convened to break the news to everyone. The newcomers had no issue with supporting the ascension of the Majority Leader. He was one of the early Democrats to break with LBJ on Vietnam, he had helped break the Dixiecrat stranglehold on committee chairmanships in the House, and he was a big supporter of social programs. Many of the class of ‘74 admired all of that, and so they would back him. By late afternoon, the press gallery was packed for the vote, having been alerted that big news was in the offing. When the chief clerk of the House began the voting process for Speaker, he acknowledged Carl Albert first after Albert said he wished to put forth a nomination for Speaker. Since the sitting Speaker never puts themselves forward, the reporters were virtually falling off of their seats as they leaned in to listen. “I stand here before you today as a proud American and a proud Okie. I have had the privilege to serve in this House, the People’s House, for some thirty years now, the last four as Speaker. I have been preceded by giants like my predecessors John McCormack and Sam Rayburn, as well as the great Henry Clay. I am no giant, as many of you have long known merely by standing next to me. [laughs from representatives] I am grateful to have served and I hope served well. I learned earlier today that I have the condition known as Parkinson’s disease, and as such, I am stepping down and will not run for Speaker of this House. Therefore, Mister Clerk, I submit the name of the honorable Thomas P. O’Neill to be the next Speaker of the House.” Albert sat down and the chamber exploded in applause and cheers, a sustained roar that compelled the retiring Speaker to stand and acknowledge it. A tear dripped from his left eye as the love of everyone in the House washed over him.

House Minority Leader Gerald Ford stood, and said that he was sad to see his friend have to step down, and as a gesture of his respect and admiration, he would cast his own vote in the Speaker race for Albert anyways. He then walked into the well, where they shook hands, and Ford placed his hand on Albert’s shoulder while leaning in and offering any help, personally, that he could provide. They then headed into the Democratic cloakroom while the vote began. The clerk would let them vote at the end, and in the meantime, the two old sparring partners sat down and had a drink. The big former athlete from Grand Rapids comforted the little giant from Bugtussle as Albert wept openly at that moment, his life’s work being cut short. Ford would not publicly tell the story until near the end of his life when he wrote his memoirs, A Ford, Not A Lincoln: My Time in Washington, D.C.

O’Neill virtually won election by acclamation, in a House dominated 2-1 by Democrats. He was the second Speaker out of the last three to be Irish Catholic, and O’Neill was the most liberal sort of Catholic, a deep believer in mercy, social justice, and aiding the sick and the poor. Like the Kennedys and other liberal Irish Catholics, Richard Cardinal Cushing had been the spiritual force in his life. Cushing’s legacy in Boston was substantive, seen in the Massachusetts congressional delegation to such a great extent that it included Father Robert Drinan, an active Jesuit priest. In his first speech from the Speaker’s chair, O’Neill would insert a line that had only been heard privately before, when he’d spoken at the graduation of his youngest son, Christopher, from Cambridge Matignon School, a Catholic prep school founded by Cushing. O’Neill said, in language one rarely heard from modern politicians, especially inside the chambers of Congress, “In everything you do, you must recall that Christ loved man and wished us, for our own sakes, to love Him. The method by which we exercise that love is by loving our fellow man, by seeing that justice is done, that mercy prevails, and the least amongst us uplifted.” It was a declaration of intent as clear as day, and it would find frequent opportunity to clash against the blunt pragmatism of President John Connally until Election Day 1976.

*****

Across the ocean, in Moscow, a rapprochement had been reached between the two sides on the Politburo. Andropov had, for now, lost. Too many men there remembered Beria, and putting a KGB chairman into the ultimate seat of power twenty years after the death of the last feared KGB chairman was a bridge too far to cross for even some of his own supporters. Alexei Kosygin, so long maneuvered out of the top spot through the cunning of Khrushchev and Brezhnev, had learned his lessons, and used them to his benefit. He was announced as the new General Secretary of the Communist Party on New Year’s Day, and then made a deal with Andropov and his old friend/rival Nikolai Podgorny to conduct the largest purge of the Politboro since Stalin’s time. Defense Minister Andrei Grechko, Ukrainian First Secretary Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, and former KGB chairman Alexander Shelepin were summarily dismissed. Andropov was named Premier, Dmitri Ustinov was promoted from candidate member to Defense Minister, Boris Ponomarev (head of the International Department of the Central Committee) was promoted from candidate member to full member, Grigory Romanov promoted from candidate member to Minister for External Economic Relations, and Georgian First Secretary Eduard Shevardnadze was promoted from candidate member to full member. Andrei Kirlienko was named Minister for Oil and Gas, tasked with modernizing their infrastructure. The new KGB chairman was Andropov’s deputy, Viktor Chebrikov. Chebrikov, along with Chairman of the Russian SSR Council of Ministers Mikhail Solomentsev and the new Justice Minister, Mikhail Gorbachev, were made candidate members of the Politburo to replace those newly promoted.

Kosygin and Andropov were of one mind: the Soviet economy needed reform, badly so, and the gross corruption that had flourished under Brezhnev had to end. The Soviets were flush with cash for the first time in decades because of the international spike in oil prices, but to maximize that advantage, they needed to change matters. Acquiring modern drilling and refining equipment was the start. Another move, long debated, was opening up additional land for private plots in agriculture. The Politburo was divided on this, but Kosygin thought the changes might just give him enough leverage to push it through. Ustinov was another modernizer, ready to propel the Soviet military forward. Grechko had made a start, but he also had made it clear he thought there would be war with the West and it would be nuclear, so he had to go. Shcherbytsky was corrupt to the core, part of Brezhnev’s claque, and nobody was sad to see him leave. Shelepin wanted his old job back, and Andropov gladly agreed to sack him. Podgorny got the Interior Ministry, another seat of power, and kept his existing portfolio.

Another move Kosygin had in mind fell in place with his longstanding beliefs about the futility of nuclear war. He wanted to declare a nuclear free-zone in Europe from the France-Germany border to the Polish-Soviet border. A missile currently under development, the SS-20, was an intermediate-range missile designed for European theater targets in NATO countries. It was costing untold amounts of money to complete, and Kosygin was tired of missile spending eating the Soviet budget alive. We can launch bombers against any European city as easily as we can lob missiles, and we have so many ICBM’s from Leonid Il’ych’s crash program to reach parity with the Americans just in time for SALT that I could retarget and ruin every nation on the planet if I were a madman. What is the point of “diversifying our arsenal,” as the Americans put it, when we already have too many of these atomic weapons already?

Kosygin picked up his phone. “Andrei Andreyevich, have Comrade Dobrynin inform Secretary Kissinger that we wish to discuss a major arms control agreement in Central Europe. Yes, tell them that you and I will sit down with Dr. Kissinger and the President. We’ll see if he’s more willing to negotiate than his stubborn cowboy mentor was at Glassboro.”

*****

Ambassador Dobrynin’s call to Henry was relayed quickly down the street to the Oval Office, where Connally sat with Adm. Burke and Ben Barnes. The NSC was already hard at work in the basement trying to determine what this shakeup in Moscow meant. It was almost a decennial event: 1954, 1964, 1974 into 1975. Each time, there had been a reshuffling of the deck, with people at the back of the succession line catapulted to the front. Some of the names were completely unknown. Shevardnadze? Gorbachev? Solomentsev? And then there was Ponomarev, essentially a rival for Gromyko’s spot as foreign minister, now sitting at the big boys table with Mr. Iron Ass himself. Kosygin, steadily pushed away from power by Brezhnev, having maneuvered himself into the top slot while bringing Andropov, his rival for that seat, along with him. The intel was sketchy, as always seemed to be the case. The CIA had not exactly covered itself in glory recruiting agents in Moscow. Things had been flat-out bleak since Penkovskiy was arrested during the Missile Crisis in ‘62. The French had some sort of midlevel agent spiriting out fighter designs, but that wasn’t political intelligence. Political intelligence was gold, and America had been, for so very long, terrible at recruiting political agents. The Brits would smile their crooked smiles and say that it’s just a matter of experience and they had not been in the game long enough yet. They did not let on a whit that they had a KGB major, Oleg Gordievsky, in their back pocket. The French would say that America never tried to lay honey traps (i.e. hookers) and that was why they failed, and the Germans...well, they were just as bad.

Connally was bothered enough by the paucity of good information that he had Nitze drive up from Langley to ask what he needed to surveil the conversations of the Politburo. Nitze replied it was impossible to gather anything from the meetings, but there might be a way, with the right type of satellite, to intercept their radiotelephone calls. The Politburo members loved their Altai phones, from which they could place calls while being driven about, using a system that was ostensibly public. Because so few Soviet citizens could afford such a luxury, or would be allowed to own one even if they could, the Politburo members treated the system as if it were secure, which was a dangerous thing to do without encryption on the system. They couldn’t use the embassy, much as they might like, because the Politburo didn’t drive past it. But a satellite in orbit would not draw the same attention, especially if disguised as a photographic reconnaissance one. Those were ubiquitous. KH-9, or HEXAGON, was currently in orbit, and its replacement, KH-11, would launch before the end of 1976, with new digital optics to provide even higher quality resolution than before. KH-10, a manned laboratory that had been canceled in 1969, had already seen its components sent away to museums and cold storage, and recovery of those would be impossible. It was Admiral Burke who came up with the idea: Why not Skylab?

Skylab’s final mission had been less than a year before. It was intended to be re-boosted by the Space Shuttle, but there was concern that the Shuttle would not be completed before it could do so. However, it was still very much in orbit, and in no danger of coming down soon. It orbited the Earth 15 times a day, which meant that deploying an intercept device on it would be much easier than a purpose-built satellite that would draw attention from Soviet reconnaissance. By announcing the restoration of the Skylab 5 mission, they would have cover to pull this off without drawing too much attention. It would simply be treated as a change in administration policy caused by the change in presidents, especially one from Texas who had a vested interest in providing extra work to the Johnson Space Center in Houston. It also would not be terribly expensive on the NASA side, and getting the appropriation would be pretty easy once the leadership was briefed. Nitze was going to dig into his “black” appropriations, but Barnes suggested that open cover was better: take money from KH-11, reprogram it for the radio-intercept attachment, and then put the money back during normal appropriations in the fall for budget year 1976. That way, any special appropriation would only be for NASA, which was still wildly popular with the public, and wouldn’t raise any eyebrows. He knew the challenge would be the House Armed Services Committee: the chairman, Mel Price, was an old-school Democrat from East St. Louis who’d play ball, but the newer members were firebrands like Les Aspin, who, in the President’s own words, “got a hard-on every time they thought about programs they could cut.” It would definitely require some arm-twisting, and that meant going to guys like Jack Brooks, Jim Wright, and maybe John McFall. Tip O’Neill, as the new Speaker, had to be briefed, so they’d ask him to get McFall involved. The Majority Whip was a former Army Intelligence NCO, and would understand. The President would do the talking with Brooks and Wright.

The Vice-President spoke up and suggested he talk with the conservatives in the Senate who would be opposed to additional spending, and had the ability to filibuster any bill that did so. Connally readily agreed. It’ll keep Ronnie out of my hair and occupy his time on something that we probably don’t need, but it doesn’t hurt to do. He’s got that trip back home to California soon to start the fundraising for ‘76, a good week up and down the state with a couple days at his ranch, too. I know I need him for the right wing support, but dammit, the man is a pain in my ass because he wants my chair and isn’t shy about showing it.

What nobody knew, least of all the President and the Vice-President, was that the pain in John Connally’s might soon be relieved by outside forces.

Best of all for Ted, having cleaned up and gotten sober, Mike Mansfield brought him back into the leadership fold as head of the Senate Democratic Policy Committee. It was Mansfield himself who’d held the position for fourteen years, and he wanted to elevate Ted’s chances in 1976. He would, in consultation with Mansfield and Robert Byrd, determine the legislation Democrats would advance between now and Election Day in 1976. All of these thoughts were running through the mind of the youngest Kennedy as he helped swear in his new colleagues. He had quietly insisted that he get to swear in the new Kansas senator, Dr. Bill Roy, because he wanted the chance to pull him aside and talk about the healthcare bill. Roy had advocated for just such a thing in the House, and as a doctor of renown, would carry weight when he spoke on the matter. Senate tradition had long dictated that you are seen, not heard, for months before you speak on the floor. Ted Kennedy had known and abided by that tradition when he’d joined the Senate, and was determined to shove it into the dustbin of history. That fealty to tradition in the Senate had created Dick Nixon and Lyndon Johnson (Teddy was friends with the deceased ex-President, but not blind to his many faults), and other leaders who’d gone morally and legally astray. Some of them were still in this room: John Stennis, James Eastland, Russell Long, Sam Ervin. Ervin was better than most of them, had definitely mellowed in the last couple of years, but the others were still pieces of work who would raise hell and complain about any subversion of their traditions. No matter. Ted knew how to work with these men, cut deals, charm them. They respected his getting sober, too, and always had some ginger ale ready for him to sip on instead of their bourbon.

A new Congress and new possibilities. Things were looking up in Ted Kennedy’s eyes.

Across the Capitol, in the back rooms of power, matters were less sanguine. Carl Albert, about to begin his fifth year as Speaker of the House, was losing his nerve. Nobody was quite sure when it started, and even Carl himself couldn’t pinpoint a time, but between the impeachment trial and the Korean crisis, the liquor wasn’t cutting it. He began to get the shakes, and while he did his best to conceal it, the whispers had been circulating around the House leadership for a couple of months now. He was not as vibrant, as engaged, as he had been before. No matter how much he’d drank in the past, it hadn’t dulled his ability to engage. Now he couldn’t control his hands and he couldn’t focus while engaged in conversation. He wanted to get through the 1976 elections, wanted to take this new and rambunctious House and guide it to safe shores. Before the swearing-in could take place, the Speaker had to be elected, and Albert had delayed the vote for a few hours. The results of his tests at Walter Reed Medical Center had come back. He had Parkinson’s Disease, and it was accelerating quickly. His cognitive test results showed decline in progress. He might be a nervous alcoholic, but at his core, Carl Albert was a man of honor for whom his oath of office meant something. It was a fairly easy decision when push came to shove. He would not stand for Speaker and would retire at the end of his term. The doctors said that the less stress he had, the slower the Parkinson’s would progress. He could be present, consult, offer guidance to the new members, but not have to bear the burden of running this madhouse. There was one thing he wanted more than anything, and that was to not be humiliated publicly. Any sort of breakdown would be all anyone remembered.

Albert scanned over the results again, sighed, and put the papers down. He tilted his head up at his guests, Majority Leader Tip O’Neill and Majority Whip John McFall. “Tip, I’m standing down, and I’m going to go to the floor and nominate you as the next Speaker. These papers here,” Albert gestured back at the desk, “say I have Parkinson’s and it’s advancing fairly quickly. I can’t stay Speaker. You’re up to bat, Tip, and I know you’re gonna be great at this job. I’ll even leave you a bottle of my best bourbon.” O’Neill chuckled, that deep rumbling Boston baritone that would become very familiar in the coming years to Americans across the country. “Carl, you’ve done a wonderful job and I’ve been proud to serve under you. The way you handled the last two years...few men could’ve done as well.”