Hi all!

So this is my first time posting in this forum. For a while now I have been extremely interested in the history of South Africa during Apartheid due to the perceived uniqueness of this situation. Additionally, I have noticed that due to the topic of Apartheid being taboo very few people bother to dig deep and uncover the underlying reasons for the system's failure. Most simply chalk it up to the impossibility of a rather small white minority ruling over an entire black country. My research into the topic, however, has revealed that Apartheid, just like many other controversial historical periods, wasn't black-and-white (pun semi-intended). Additionally, the collapse of Apartheid wasn't a foregone conclusion until the mid to late 1980's. There were, indeed, many efforts to preserve Apartheid, especially by reforming it. Therefore, over the past few weeks I've been writing an alternate history scenario in which the white government of South Africa resolves to try and maintain its system of racial segregation through various means. This scenario is largely based on real historical facts and events supplemented with fictional elements here and there to make the scenario work. The story starts in 1978 with the election of PW Botha as Prime-Minister and the POD is in 1980.

I've done a lot of research writing this piece and I hope that you not only enjoy it but also find it plausible enough. Of course, as I am extremely interested in the topic, I will welcome any criticisms, accusations of ASB's and informed opinions contributing to a general discussion of history and specifically the likelihood of this scenario.

Lastly, I feel obligated to say that I do not hold any White Supremacist views and, in general, do not support Apartheid, especially in the way that it was implemented OTL.

Having said all of this, I hope you guys enjoy the first two Chapters.

South Africa: Birth of a New Nation

The Black Question

On 9 October 1978 Pieter Willem Botha was narrowly elected as the new leader of the ruling National Party of South Africa and consequently Prime-Minister of the country. The 62 year old veteran politician inherited an Apartheid system that, having been in place since 1948, had slowly begun to show its cracks. The growing internal opposition to the system was becoming more and more violent with organizations such as SWAPO in Namibia and the ANC openly waging war against the authorities. To make matters worse, this internal discontent was starting to be reflected on the world stage with numerous governments considering far-reaching sanctions against the Apartheid government. Change was needed. Botha, although considered a relative moderate among his party’s ranks, believed in the system and had no intention of abolishing it. However, realizing that white minority rule could not continue indefinitely, Botha decided to pursue reform. There had always been many anti-Apartheid activists who claimed the system could not be reformed and called for its outright abolition. The majority of the international community, however, was not that extreme in its demands. Changes of any kind, as long as honest and effective, would be seen as a substantial improvement to the situation as a whole, a first step towards true change.

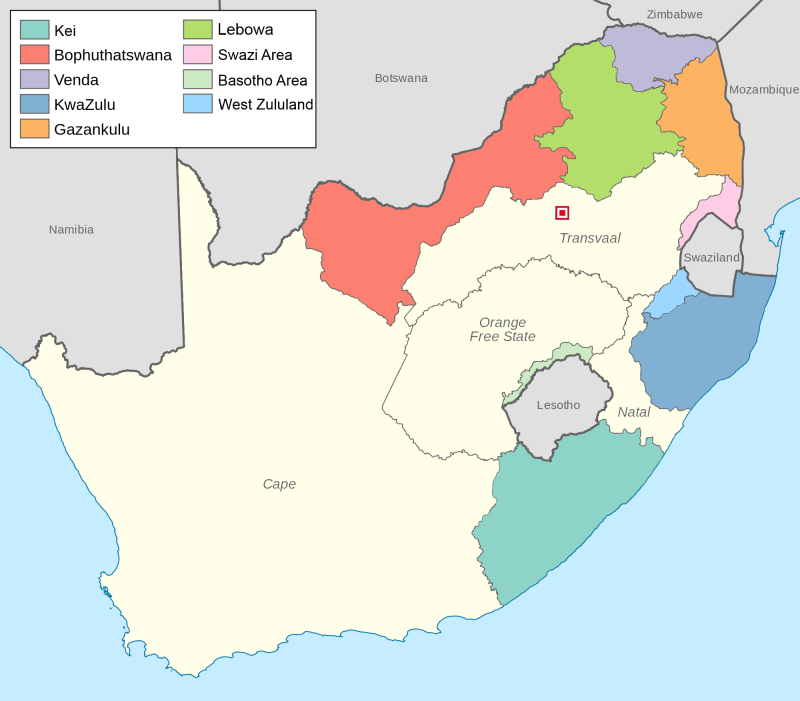

Botha, as Prime-Minister, first wanted to address what he saw as the most pressing problem – the Swart Gevaar or Black Threat. The rapid growth of the black Bantu population coupled with its increasing political aspirations had always presented a complex problem for the government. A central idea of Apartheid addressing this problem was the Bantustan system, a program that had led to the establishment of several self-governing black ‘homelands’. The end result of this project was to be the segregation and separation of blacks into their homelands on the basis of ethnicity. However, the territories set aside for the purpose were small and disconnected from one another, rendering most of these quasi-states nothing more than a patchwork of ungovernable exclaves. Botha had always been aware of the flaws in the system so he resolved that in order for it to work these administrative entities would have to become more state-like and less resembling black reservations. To that end, in early 1980 he introduced two bills that would change the history of the country forever. After a fiery debate Botha managed to impose his will on those opposing his reforms and so, on 20 March the South African Parliament passed the Homeland Territorial Act (HTA) and the Homeland Repatriation Act (HRA). The laws begun to restructure the homelands, especially the HTA which redrew their borders. All were allocated additional land so that their combined, newly contiguous territory now constituted more than a third of the total area of South Africa. The resulting six homelands were, namely, Lebowa, Gazankulu, KwaZulu, Venda, Bophuthatswana and the Kei. The last two had become independent already under Botha’s predecessor Vorster with the Kei being the new name of Transkei after its incorporation of Ciskei, another Xhosa homeland. Additionally, the Basotho Strip and Northern Swazi Territories were created along the borders of Lesotho and Swaziland respectively as special areas under direct South African administration. Later on, in 1985-89 South Africa would implement the HRA through a ruthless programme of population displacement, sometimes forced, to bring about the ‘repatriation’ of the entire black population to the homelands, a grandiose project that would lead to regional conflicts lasting for years.

The Nationality Question

Addressing the black question was only the beginning for Botha. After four years at the helm of the country he felt that reform was not quick or palpable enough. It would take years before the black homelands became ready for full independence, Apartheid’s end goal. Meanwhile South Africa remained, in the eyes of the world, a racist and oppressive regime. Support was hard to come by both internationally and domestically. On top of that, at home there were still millions of Coloured and Asian South Africans whose fate in the nation was at that time unknown. As different from the blacks, they did not fall under the Bantustan system, but weren’t considered citizens by the Pretoria government either. What is more support for Apartheid was beginning to wane even amongst some of the white population. Botha realized that in order to make the system more popular he needed to make it more inclusive.

Beginning in the early 1980s the emphasis of the National Party’s ideology began to shift from race to culture. Increasingly, European roots and language replaced skin color as the defining feature of the nation. This trend culminated in 1982 with the passing of the National Citizenship Act, a law that granted full citizenship with equal rights to South African Coloureds and Asians, both in South Africa and South West Africa/Namibia, at that time under Pretoria’s administration. The opposition to the law was intense. Botha however, managed to convince Parliament that the changes were necessary if the system was to survive at all. ‘Adapt or die’ were his famous words. He argued that on the basis of their language, religion and ancestry the Coloureds were far closer to the whites than to the blacks. After all, the vast majority had white European ancestry, mostly spoke Afrikaans and a minority English as their mother tongue, and practiced Christianity. Therefore, they would integrate more easily into the nation, despite not being white. It was decided that Asians, of whom most were Indian South Africans, would also be granted citizenship, as they did not belong to the black homelands either. Following the passage of the law the country’s citizenry basically doubled over-night. Most of the new citizens felt gratitude towards the Party for finally recognizing them as equal to the whites and were willing to vote accordingly. These dramatic changes did not leave Botha’s party itself unscathed, however, as many of its ultra-conservative members who found the reforms too hard to stomach split from the NP and formed the new Conservative Party led by Andries Treurnicht. This new party would become the main parliamentary opposition replacing the Progressive Federal Party. The progressives had long opposed Apartheid and had campaigned for its abolition. Many of its followers, however, were beginning to be appeased by Botha’s reforms leading to a gradual decline in the Party’s popularity.

The drastic and somewhat controversial changes brought about by the National Citizenship Act were further solidified in 1983 when Botha had a new Constitution for South Africa approved by Parliament. This came on the heels of a constitutional referendum approved by 56%, the last white-only vote to take place. The Constitution led to the abolition of the upper chamber of the legislature resulting in a unicameral Parliament. Furthermore, Botha’s own office, that of Prime-Minister, was abolished and its powers were transferred to that of State President, a formerly ceremonial post for which Botha would run in the following year’s General Elections.

So this is my first time posting in this forum. For a while now I have been extremely interested in the history of South Africa during Apartheid due to the perceived uniqueness of this situation. Additionally, I have noticed that due to the topic of Apartheid being taboo very few people bother to dig deep and uncover the underlying reasons for the system's failure. Most simply chalk it up to the impossibility of a rather small white minority ruling over an entire black country. My research into the topic, however, has revealed that Apartheid, just like many other controversial historical periods, wasn't black-and-white (pun semi-intended). Additionally, the collapse of Apartheid wasn't a foregone conclusion until the mid to late 1980's. There were, indeed, many efforts to preserve Apartheid, especially by reforming it. Therefore, over the past few weeks I've been writing an alternate history scenario in which the white government of South Africa resolves to try and maintain its system of racial segregation through various means. This scenario is largely based on real historical facts and events supplemented with fictional elements here and there to make the scenario work. The story starts in 1978 with the election of PW Botha as Prime-Minister and the POD is in 1980.

I've done a lot of research writing this piece and I hope that you not only enjoy it but also find it plausible enough. Of course, as I am extremely interested in the topic, I will welcome any criticisms, accusations of ASB's and informed opinions contributing to a general discussion of history and specifically the likelihood of this scenario.

Lastly, I feel obligated to say that I do not hold any White Supremacist views and, in general, do not support Apartheid, especially in the way that it was implemented OTL.

Having said all of this, I hope you guys enjoy the first two Chapters.

South Africa: Birth of a New Nation

The Black Question

On 9 October 1978 Pieter Willem Botha was narrowly elected as the new leader of the ruling National Party of South Africa and consequently Prime-Minister of the country. The 62 year old veteran politician inherited an Apartheid system that, having been in place since 1948, had slowly begun to show its cracks. The growing internal opposition to the system was becoming more and more violent with organizations such as SWAPO in Namibia and the ANC openly waging war against the authorities. To make matters worse, this internal discontent was starting to be reflected on the world stage with numerous governments considering far-reaching sanctions against the Apartheid government. Change was needed. Botha, although considered a relative moderate among his party’s ranks, believed in the system and had no intention of abolishing it. However, realizing that white minority rule could not continue indefinitely, Botha decided to pursue reform. There had always been many anti-Apartheid activists who claimed the system could not be reformed and called for its outright abolition. The majority of the international community, however, was not that extreme in its demands. Changes of any kind, as long as honest and effective, would be seen as a substantial improvement to the situation as a whole, a first step towards true change.

Botha, as Prime-Minister, first wanted to address what he saw as the most pressing problem – the Swart Gevaar or Black Threat. The rapid growth of the black Bantu population coupled with its increasing political aspirations had always presented a complex problem for the government. A central idea of Apartheid addressing this problem was the Bantustan system, a program that had led to the establishment of several self-governing black ‘homelands’. The end result of this project was to be the segregation and separation of blacks into their homelands on the basis of ethnicity. However, the territories set aside for the purpose were small and disconnected from one another, rendering most of these quasi-states nothing more than a patchwork of ungovernable exclaves. Botha had always been aware of the flaws in the system so he resolved that in order for it to work these administrative entities would have to become more state-like and less resembling black reservations. To that end, in early 1980 he introduced two bills that would change the history of the country forever. After a fiery debate Botha managed to impose his will on those opposing his reforms and so, on 20 March the South African Parliament passed the Homeland Territorial Act (HTA) and the Homeland Repatriation Act (HRA). The laws begun to restructure the homelands, especially the HTA which redrew their borders. All were allocated additional land so that their combined, newly contiguous territory now constituted more than a third of the total area of South Africa. The resulting six homelands were, namely, Lebowa, Gazankulu, KwaZulu, Venda, Bophuthatswana and the Kei. The last two had become independent already under Botha’s predecessor Vorster with the Kei being the new name of Transkei after its incorporation of Ciskei, another Xhosa homeland. Additionally, the Basotho Strip and Northern Swazi Territories were created along the borders of Lesotho and Swaziland respectively as special areas under direct South African administration. Later on, in 1985-89 South Africa would implement the HRA through a ruthless programme of population displacement, sometimes forced, to bring about the ‘repatriation’ of the entire black population to the homelands, a grandiose project that would lead to regional conflicts lasting for years.

The Nationality Question

Addressing the black question was only the beginning for Botha. After four years at the helm of the country he felt that reform was not quick or palpable enough. It would take years before the black homelands became ready for full independence, Apartheid’s end goal. Meanwhile South Africa remained, in the eyes of the world, a racist and oppressive regime. Support was hard to come by both internationally and domestically. On top of that, at home there were still millions of Coloured and Asian South Africans whose fate in the nation was at that time unknown. As different from the blacks, they did not fall under the Bantustan system, but weren’t considered citizens by the Pretoria government either. What is more support for Apartheid was beginning to wane even amongst some of the white population. Botha realized that in order to make the system more popular he needed to make it more inclusive.

Beginning in the early 1980s the emphasis of the National Party’s ideology began to shift from race to culture. Increasingly, European roots and language replaced skin color as the defining feature of the nation. This trend culminated in 1982 with the passing of the National Citizenship Act, a law that granted full citizenship with equal rights to South African Coloureds and Asians, both in South Africa and South West Africa/Namibia, at that time under Pretoria’s administration. The opposition to the law was intense. Botha however, managed to convince Parliament that the changes were necessary if the system was to survive at all. ‘Adapt or die’ were his famous words. He argued that on the basis of their language, religion and ancestry the Coloureds were far closer to the whites than to the blacks. After all, the vast majority had white European ancestry, mostly spoke Afrikaans and a minority English as their mother tongue, and practiced Christianity. Therefore, they would integrate more easily into the nation, despite not being white. It was decided that Asians, of whom most were Indian South Africans, would also be granted citizenship, as they did not belong to the black homelands either. Following the passage of the law the country’s citizenry basically doubled over-night. Most of the new citizens felt gratitude towards the Party for finally recognizing them as equal to the whites and were willing to vote accordingly. These dramatic changes did not leave Botha’s party itself unscathed, however, as many of its ultra-conservative members who found the reforms too hard to stomach split from the NP and formed the new Conservative Party led by Andries Treurnicht. This new party would become the main parliamentary opposition replacing the Progressive Federal Party. The progressives had long opposed Apartheid and had campaigned for its abolition. Many of its followers, however, were beginning to be appeased by Botha’s reforms leading to a gradual decline in the Party’s popularity.

The drastic and somewhat controversial changes brought about by the National Citizenship Act were further solidified in 1983 when Botha had a new Constitution for South Africa approved by Parliament. This came on the heels of a constitutional referendum approved by 56%, the last white-only vote to take place. The Constitution led to the abolition of the upper chamber of the legislature resulting in a unicameral Parliament. Furthermore, Botha’s own office, that of Prime-Minister, was abolished and its powers were transferred to that of State President, a formerly ceremonial post for which Botha would run in the following year’s General Elections.

Last edited: