The great events of history are often surrounded by their own mythology, which at the same time as it celebrates and aggrandizes history often warps it, forcing historians to cut through layers of legend to arrive to a less glamorous truth. The Civil War is no exception; indeed, it might be one of the most relevant examples, for its centrality to American history and identity has resulted in the construction of clear, heroic narratives. Abraham Lincoln himself is a prime example. John Wilkes Booth’s atrocious attempt on Lincoln’s life came to form part of the story of the “Great Emancipator”, whose humanity had led him to compassionately but misguidedly try to forgive the rebellious Southerners. While borne out of mercy, this magnanimity only emboldened the traitors and divided the Republican Party between the foolishly compassionate and the foolishly vindictive. Having survived the attack, Lincoln then realized that real justice involved punishing the wealthy planters, who had deluded common men like Booth into committing terrible acts. This realization, as momentous as his recognition that slavery had to be destroyed in 1862, allowed Lincoln to unite the Republican Party behind him and his wise policy, that balanced charity and justice to achieve the best for the nation.

At its most extreme, this interpretation of history has said that Booth indirectly saved the Republican Party and even the United States, because his actions, horrifying as they were, helped Lincoln realize that the Southern Slavocracy would resort to anything to preserve its power. While maintaining his compassion for those who had been deluded to fight for a cause that didn’t favor them, Lincoln “saw the light” and undertook a policy that sought to overthrow the slavocracy, the truly guilty for the tragedy of the war. The Republican Party, until then vacillating and divided, found new and greater strength in Lincoln’s program, and united to renominate and then re-elect him. Booth, the tragic victim, then joined the long list of Southerners who in trying to avoid a radical revolution ended up sparking one. Lincoln, the tragic hero, for his part joined the long list of Northerners who offered mercy to the enslavers, only to see violence and evil returned. Ultimately, similarly to how the war was necessary despite its tragic cost, the assassination attempt was likewise necessary, because it reunited the Republican Party and spurned Lincoln to take the final, most important step in his growth as a statesman.

Needless to say, the truth is much more complex. The idea that the war represented a continuous evolution of Lincoln’s thought and actions is an enduring one because in some ways it is true. At the very start of the war Lincoln had argued against letting the war become a remorseless radical struggle, but, by the time Booth and his conspirators acted, Lincoln was leading just that kind of revolutionary crusade. However, just like how Emancipation wasn’t a sudden realization but the product of careful consideration and the events of the first year of war, Lincoln’s Reconstruction policy wasn’t an unexpected development. Three hard years of war, the politics of the North, and the strife within the Republican Party are all factors that must be considered and probably weighted more on Lincoln’s mind than the traumatic attempt on his life when it came to fashioning a peace. The myth that the assassination gave Lincoln a necessary “final push”, at the same time as it united the Republican Party and the whole North behind a new policy that Lincoln created at that moment is, in the last analysis, simply untrue.

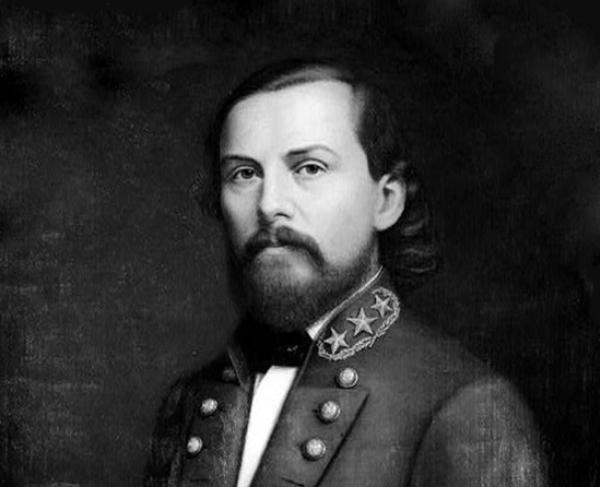

A more truthful recounting of events is not only essential, but more useful for it allows for a better understanding of the inner politics of the Republican Party, showing the political brilliance of Abraham Lincoln. As already related in previous chapters, the Southern Territories Bill that Lincoln vetoed in late April wasn’t merely a factional challenge against his leadership, but the product of genuine constitutional and ideological concerns. Otherwise, the legislation wouldn’t have commanded a near unanimity among Republicans ranks. Presidential politics didn’t play a large role in the making of the bill, but Lincoln’s veto and the subsequent reactions did demonstrate the differing concerns of each Republican faction and contributed to defining the position of every Republican in the up-coming contest. More relevantly, and especially among Radicals, it solidified already held doubts about Lincoln and reinforced an already present, if previously beneath the surface, commitment to replace him as the candidate for 1864.

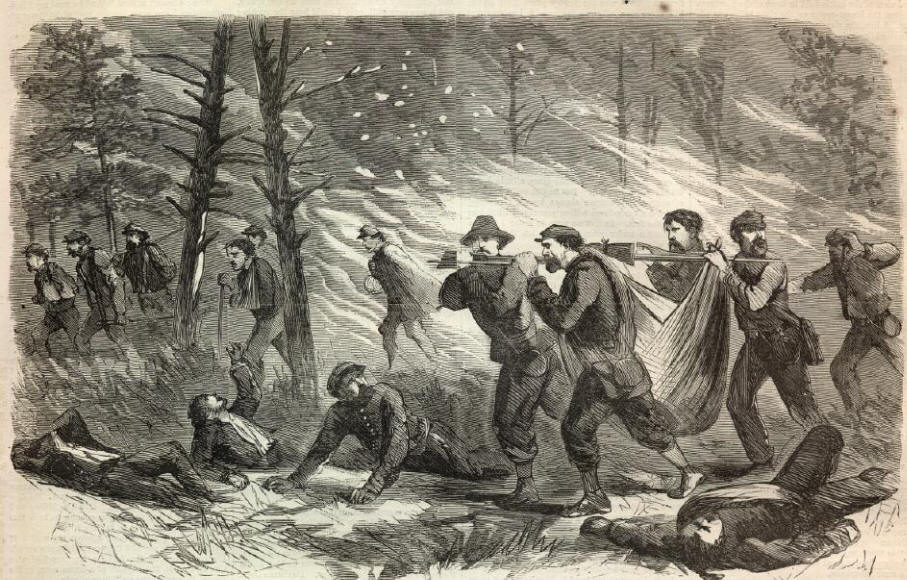

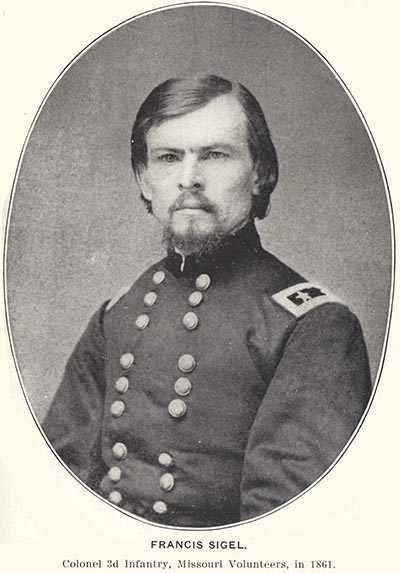

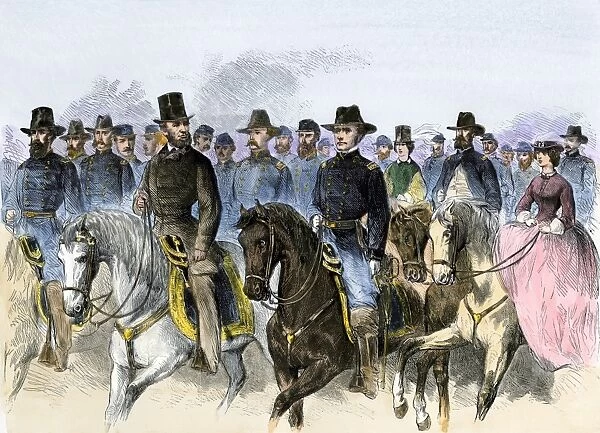

Booth's attempts hallowed Lincoln even more in Northern hearts

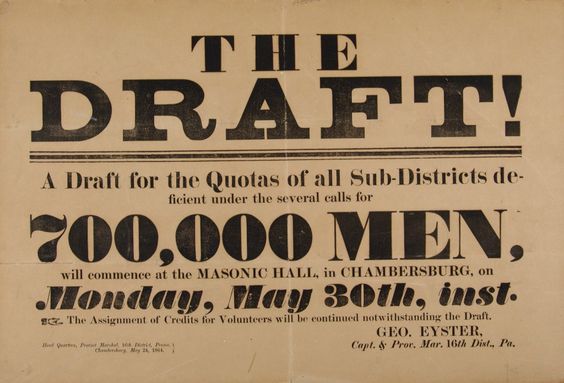

Several factors were operating against Lincoln’s reelection. Since Martin Van Buren 1840 no incumbent had been renominated, and none had won since Andre Jackson in 1832. With usual lack of expressiveness, Lincoln merely said that “a second term would be a great honor and a great labor, which together, perhaps I would not decline, if tendered”, when questioned by close confidantes, but in truth the President did desire to be reelected, both as personal vindication and to further his policy. By the end of 1863, it was clear that Lincoln would be a candidate again. Even if, by custom, he could not announce his intentions or campaign for himself directly, his friends moved behind the scenes to secure support for his renomination. To assemble a broad coalition behind him, Lincoln gave attention to both Conservatives and Radicals. For example, he sought to mollify the Blairs and Weeds of the Party, at the same time as he lavished kindness on Radicals like Sumner, who became a frequent visitor to the Executive Mansion. There, the Senator and Lincoln would “laugh together like two school boys”, according to Mary Lincoln.

However, despite these efforts, there were already many important segments of the Party that had been alienated by Lincoln’s conduct of the war, such as an Iowa caucus that denounced Lincoln for having “clogged and impeded the wheels and movements of the revolution”. Even as the Republican Party and the North as a whole came to agree on the goals of the war, namely Black emancipation and unconditional victory, many remained skeptical that Lincoln was capable of achieving them. Few Congressional leaders seemed enthusiastic about a second Lincoln term, with many still convinced, as they had been in 1860, that there were better men available. “You would be surprised in talking with public men,” a conservative wrote in February 1864, “to find how few . . . are for Mr. Lincoln’s reelection. There is a distrust and fear that he is too undecided and inefficient ever to put down the rebellion”. Even those who thought the President’s mind “works in the right directions”, like Henry Ward Beecher, believed that he lacked the “element of leadership” that would allow him to convert just principles into practical, permanent solutions.

Yet, despite the opposition of several key figures, Lincoln seemed to find greater support among the people. His friends and a deluge of letters from all over the North assured Lincoln that “you have touched and taken the popular heart—and secured your re-election beyond a peradventure—should you desire it.” James A. Garfield, recently elected to Congress after a gallant career in the Army of the Cumberland, concluded that “The people desire the reelection of Mr. Lincoln”. To be sure, some of this support had been ably fostered by Lincoln by means of patronage and political maneuvering. Nonetheless, and especially in the Republican center, many agreed that Lincoln was the best choice. But the dangerous discontent of several powerful men remained, and resulted in two distinct political movements in the first half of 1864. The first, coming from the Radicals, sought to make the Republican Party replace Lincoln with a more radical candidate; the second, coming from Conservatives, wished to make Lincoln repudiate the Republican Party in favor of a more conservative coalition.

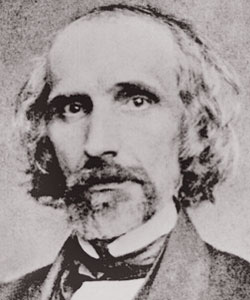

The man at the center of the first movement was Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. “I think a man of different qualities from those the President has will be needed for the next four years”, Chase wrote at the end of 1863, doubtlessly convinced that he was that man. Chase used his position as Secretary of the Treasury to build a base of support through patronage, and sought those who felt slighted by Lincoln to assure them that if he were President things would be different. Lincoln for the most part didn’t pay any mind to Chase’s efforts. “I am entirely indifferent as to his success or failure in these schemes”, Lincoln said with confident amusement, “so long as he does his duty as the head of the Treasury Department.” His confidence was based on his strength. Lincoln’s partisans seemed more successful than Chase’s in the early months of 1864, when their organization extracted votes of confidence from several Northern state legislatures and conventions, including the endorsement of all Republicans in the legislatures of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Kansas, and California.

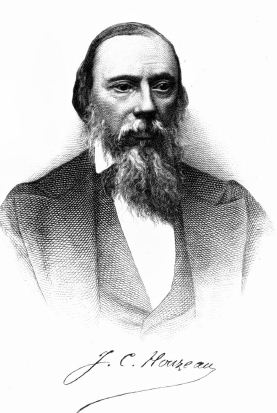

The efforts of the Secretary’s friends were nowhere near as fruitful. They started in earnest in January 1864, when powerful friends including the financier Jay Cooke, the reporter Whitelaw Reid, and Senators Samuel Pomeroy and John Sherman, inaugurated a “Chase for President” committee. They first indirectly, and without naming Chase, advocated his candidacy in a pamphlet titled “The Next Presidential Election”. This was followed up with an even more vicious assault in the form of a circular distributed by Senator Pomeroy among hundreds of Republican politicians across the North. Declaring that Lincoln’s reelection was “practically impossible”, the Pomeroy Circular unabashedly pressed Chase’s candidacy forward, for he was a “a statesman of rare ability, and an administrator of the very highest order”. If somehow reelected, Lincoln, with his “manifest tendency toward compromises and temporary expedients of policy”, would just preside over a second term where “the cause of human liberty, and the dignity and honor of the nation, suffer proportionately, while the war may continue to languish”.

The indiscreet heavy-handed methods of Chase’s friends backfired almost immediately. Lincoln’s supporters, upon learning of this “most scurrilous and abusive circular”, united in defense of the President and denunciation of Chase and his men. A correspondent warned Senator Sherman, who had helped distribute the Circular, that this attempt of a “few politicians at Philadelphia” to turn the people against “Old Honest Abe” was doomed to failure. As Gideon Welles observed, the Circular’s “recoil will be more dangerous I apprehend than its projectile” for it would “damage Chase more than Lincoln”. A second round of endorsements and a flurry of pro-Lincoln counter-circulars led the hitherto Chase-friendly

New York Times to acknowledge the “universality of popular sentiment in favor of Mr. Lincoln’s reelection”. “Nothing can overcome it or seriously weaken” this support, the paper concluded. Several of Chase’s supporters were so chastened by this reaction that they hopped off the Chase bandwagon.

The Secretary himself was so chagrined by “this boomerang destruction of his aspirations” that he disingenuously asserted that he was not consulted about the Circular and would not have approved its contents had he known. Asking Lincoln to not “hold me responsible except for what I do or say myself”, Chase nevertheless offered his resignation to Lincoln, claiming that he did “not wish to administer the Treasury Department one day without your entire confidence.” Several supporters wanted him to accept Chase’s resignation, including Lincoln’s personal friend David Davis, who stated that he “wd dismiss him [from] the cabinet if it killed me.” But Lincoln recognized that Chase was more dangerous out of the government than inside of it. The very fact that Chase led “such an intrigue against the one to whom he owes his portfolio”, weakened him, recognized Frank Blair, speculating that Lincoln only retained him because “every hour that he remains sinks him deeper in the contempt of every honorable mind.”

All this contributed to creating an image of Chase as cowardly and dishonorable, for if he had “courage and manliness enough”, a representative remarked acridly, he would surrender his post and openly challenge Lincoln, instead of “exposing his friends to ridicule and abandoning them fast lest he be a target too”. Lincoln himself mocked Chase’s ambitions as a form of “mild insanity”, assuring Edward Bates that Chase and other malcontents would not dare attack him because they “fear that the blow would be ineffectual, and so, they would fall under his power, as beaten enemies.” Lincoln, a Pennsylvania supporter concluded, was hiding “his keen and sometimes bitter resentment against Chase, and waited the fullness of time when he could by some fortuitous circumstance remove Chase as a competitor, or by some shrewd manipulation of politics make him a hopeless one.”

The fatal blow that finally rendered Chase’s candidacy “a hopeless one” came shortly after the Pomeroy Circular, when the Lincoln forces were able to secure a unanimous endorsement of Lincoln from the Republicans in the Ohio legislature. Now secure in his position, Lincoln decided to retain Chase in the Cabinet. A few days later, a “sore and unhappy” Chase withdrew from the contest. Despite this public disavowal, many thought that Chase would leap again at the chance to be nominated if the opportunity arose. Yet, even after Chase withdrew from the race, several Radicals conspired to either bring him back or bolt to a new Party. The two main factors behind the continuous scheming and discontentment of the Radicals was the seeming reluctance to fully embrace Reconstruction, shown in his Louisiana policy and the veto of the Southern Territories Bill, but also in his lack of open support for the Constitutional Amendment the Congress had been drafting since late 1863.

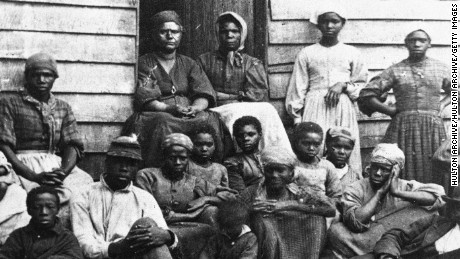

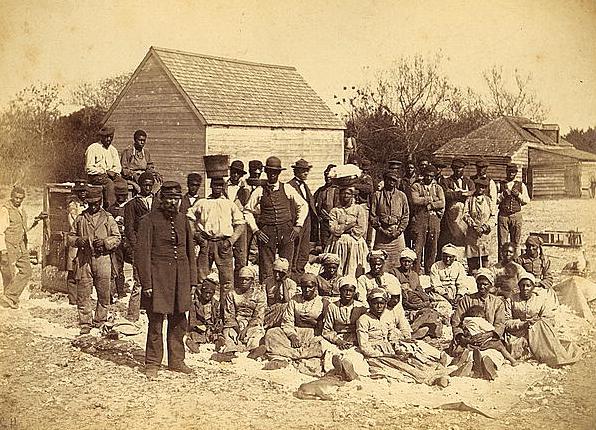

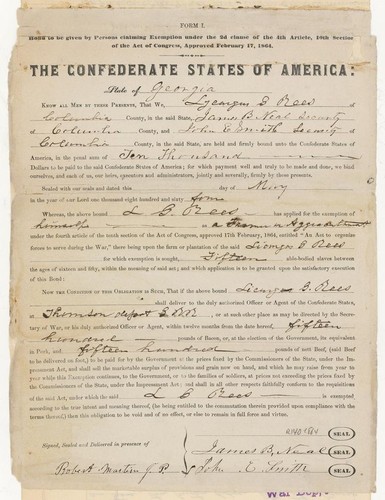

Republicans had arrived at the conclusion that an amendment was necessary to fully destroy slavery in the latter half of 1863. For years, a pillar of anti-slavery politics had been that the odious institution was weak, that it would easily collapse if subjected to the strain of war. “Disunion is abolition”, Republicans warned during the secession crisis, predicting that slavery would easily collapse. Yet, even after three years of war and despite the commitment of the Union Army to military emancipation since the Proclamation was signed in 1862, slavery proved to be sturdier than previously thought. None of the proclamations and laws had “reached the root of slavery and prepared for the destruction of the system”, asserted one Congressman. “We have made some men free, but the system yet lives.” Slavery, another representative declared, was a “condemned” but “unexecuted culprit”. Given that it was not dead, “should we not recognize the fact and provide for the execution?”

Political cartoon mocking Chase's lack of success

But the form the death sentence was to take was still hotly debated. One possible approach, mostly favored by Lincoln, was abolition at the state level. Federal pressure would eventually result in abolition in Maryland, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Missouri, but that laid months in the future when in December 1863 the Thirty-Eighth Congress started its first regular session. More critically, if the States could abolish slavery, then they could also reestablish it eventually. Only Federal power seemed capable of securing the destruction of slavery and preventing the reenslavement of those who had already been freed. At first, some Republicans believed they could invoke this power by means of ordinary legislation. Early on the session, Senator John Hale thus introduced a bill that abolished slavery legislative. But, as historian James Oakes explains, Hale’s bill went against the Federal consensus that the Republican Party had upheld and respected since its inception: that the Constitution protected slavery and Congress had no power to directly interfere with it in the States.

A few Republicans, including Hale and Sumner, had abandoned this consensus recently, arguing instead that the Founders had, in truth, created an anti-slavery document that empowered Congress to abolish slavery everywhere. If Northerners had previously believed that slavery was protected in the States, they asserted, it was only because of the distortions of the Slave Power. This new position coincided with the launching of a “fresh moral agitation” by Northern abolitionists, which saw Congress inundated by petitions and letters, including a “monster” petition with over 100,000 signatures recollected by the Women’s National Loyal League, and delivered to the Senate by two Black men. Despite these efforts, the great majority of Republicans clung to the idea that Congress could not abolish slavery on its own power because the Constitution did not grant the power.

Yet, Republicans had also reached the conclusion that slavery had to be destroyed. The logical answer was then that the Constitution itself had to be changed to destroy slavery and grant the national government the power to enforce emancipation. “The only effectual way of ridding the country of slavery”, concluded a Senator, “and so that it cannot be resuscitated, is by an amendment to the Constitution”. Though a logical, almost obvious step, amending the Constitution had not been considered even by abolitionists because the document had been “almost universally revered as the capstone of the American Revolution—the near-perfect handiwork of the Founders”. Abolitionists had spent several decades arguing that the Founders had been actually against slavery and had carefully constructed an anti-slavery reading of the Constitution. This had been necessary to justify anti-slavery policies, but also to conciliate the Northern people’s admiration for the Founders by invoking the “ultimate extinction” of slavery as what they had wanted.

The Republicans’ decision to amend the Constitution precipitated the “end of the Federal consensus”, as Republicans presented a new understanding of the relationship between the Constitution and slavery. “In the prewar telling, slavery would be overthrown when the Slave Power was dislodged and the original meaning of the Constitution was restored”, James Oakes explains. But, “in the revised version the Founders were certainly well intentioned, yet they had made a fatal mistake”, when they compromised with slavery, believing it was already dying. “But slavery didn’t die”, Oakes continues, “it flourished, and the Slave Power flourished with it, thanks to the fatal concessions the Founders had made to slavery at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.” Instead of being infallible, the Founders had been mistaken, “eluded and deceived” by the Slave Power when they had at first “believed slavery would wither and die beneath rays of the Christian and democratic institutions they founded”, related Henry Wilson. Just like the Founders in 1787, Republicans in 1864 had weakened slavery, but they could not repeat their forefathers’ mistakes and allow it to survive.

Two versions of the amendment were introduced, the first being a “conservative” one in the House which invoked the language of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction”. However, Charles Sumner, considering the wording of “the Jefferson ordinance” insufficient, introduced an alternate “radical” amendment that instead harkened to the French Declaration of the Rights of Man: “all persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave.” At first it seemed like Sumner’s version would be defeated, with Senator Howard rebuking his college for referencing “French constitutions or French codes” and insisting he “go back to . . . good old Anglo-Saxon language”. Sumner at first seemed willing to concede defeat, but the convergence of the amendment with the Southern Territories Bill resulted in a desire for a more radical amendment.

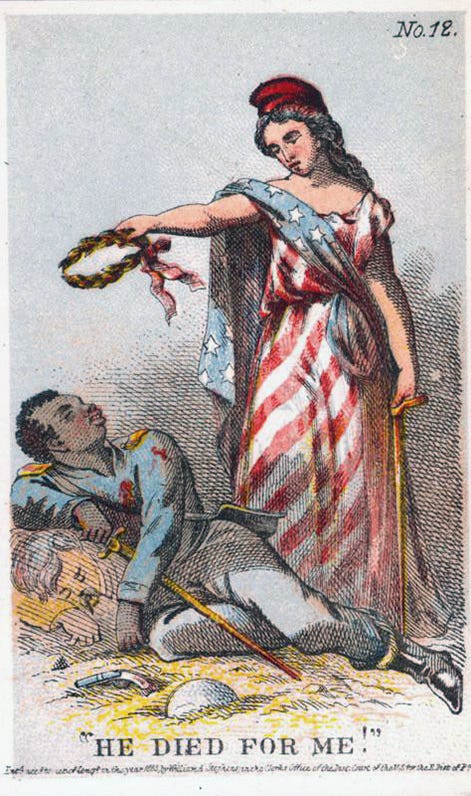

Female abolitionists played an important part in the destruction of slavery

The reasons behinds the amendment here discussed – the desire to secure the destruction of slavery, anxiety over the future of the freedmen, a certainty that Lincoln’s military powers hadn’t adequately prepped the ground for Reconstruction – are all also reasons for Republican support for the Southern Territories Bill. It might seem puzzling, then, that the Congress advanced both measures simultaneously. But this misunderstands the essential fact that the amendment and the bill responded to different, if related, concerns, providing distinct solutions for distinct problems. The bill was meant to secure Reconstruction; the amendment to secure Emancipation. For Republicans, these goals were intertwined, for Reconstruction couldn’t be without Emancipation. But they had concluded that legislative emancipation wasn’t possible. An Emancipation amendment was then necessary for the bill to be effective. Consequently, there was no reason why the bill and the amendment couldn’t be worked on at the same time, as they were during the first months of 1864.

Yet, as the months progressed, the amendment ran intro trouble. Unlike a legislative act, which only needed a majority, an amendment would need a two-thirds supermajority. Republicans, on account of their strong performance in the 1862 midterms, had secured it in both Houses of Congress, but they were thin, brittle majorities. This meant that the agreement of almost every single Republican would be needed for the amendment to pass, and this wasn’t a sure thing. Part of the problem was that the President remained aloof from the debate. t's possible that Lincoln still believed that the state-by-state basis he was enacting through the Quarter Plan was the better choice, and feared that endorsing the amendment would undermine his efforts. In any case, even the most conservative Republicans still believed that the amendment was good policy.

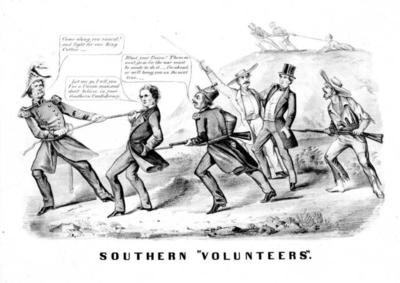

Reverdy Johnson proved to be a lonely Chesnut voice in favor of the amendment when he declared slavery “an evil of the highest character”, and its destruction a prerequisite to “a prosperous and permanent peace”. The rest started a fiery counterattack. The arguments they wielded were familiar in their racism, yet the debate is still extraordinary because it was the first national debate where both factions openly and honestly focused on slavery itself. Despite electoral defeats, internal divisions, and political suppression, the Chesnuts closed ranks, because whatever divisions affected their party they could agree on the essential argument that slavery had to be preserved for the benefit of the White man. Emancipation, they argued, would lead to the “amalgamation” of the races, and would “set free four million ignorant and debased negroes to swarm the country with pestilential effect.” Condemning how the Union Army was sweeping the South “with a sword in one hand and a fire-brand in the other, burning and destroying as they went, in order to . . . wipe out the white people of the country and supplant them by black free men”, Chesnuts presented themselves as the merely performing their “high and patriotic duty to let the negro slide”.

Republican attempts to force Emancipation were just “a tyrannical destruction of individual property”. Opening a letter from Fernando Wood, who had fled to Europe due to his links with the New York riots, a Chesnut representative effected tears as he talked of “my persecuted colleague, for whom a dreary dungeon or a despot’s firing squad await for the crime of defending property and constitutional government”. His reading of the letter was interrupted by heckling led by Thaddeus Stevens, who exclaimed that if Lincoln was such a tyrant “you, sir, would be hanging from a hemp rope right now – as you and all other traitors ought to!” Nonetheless, Wood’s argument that the amendment would “alter the whole structure and theory of government by changing the basis upon which it rests”, was echoed by other Chesnuts, like Kentucky’s Robert Mallory who warned that if the States’ right to decide on slavery was overturned, “One after another right will be usurped . . . until all State rights will be gone, and perhaps State limits obliterated.”

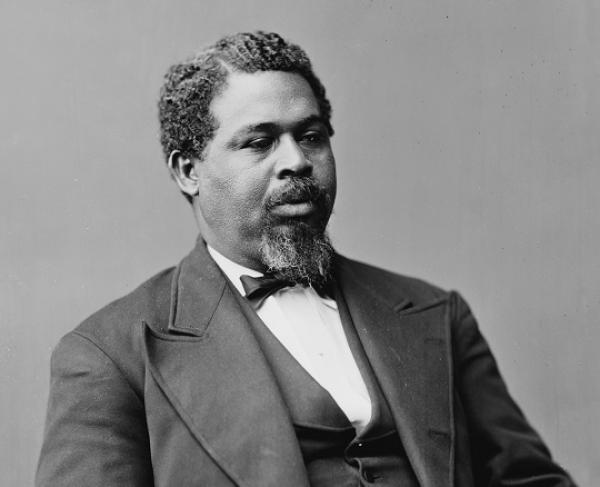

As almost always, Republicans paid little mind to these arguments, but still felt the need to respond to them. What’s truly interesting is not the racism of the conservative speeches, for this was usual, but the fact that Republicans were now openly defending the rights of Black people. Beyond the usual denial of the right of “property in man”, long a pillar of their thought, Republicans now asserted the citizenship of Black people and even mocked “the claims for Black racial inferiority”. Senator Howe said that the idea that Black people “as a race are inferior to the whites” was the “one single excuse . . . more odious than the crime” of slavery itself. The amendment would give birth to a “new nation” where “liberty, equality before the law is to be the great cornerstone”, insisted Arnold. To end “the defiant pretensions of the master, claiming control of his slave”, Sumner said, they would, through the amendment and the Southern Territories bill, empower to National government to protect the freedom they were granting. As the

Chicago Tribune summarized, “events have proved that the danger to . . . freedom is from the states, not the Federal government.”

Charles Sumner speaking in favor of the amendment

In early April, with a unanimous Republican vote and with the support of some Northern and Border State Chesnuts, the “conservative” version of the amendment was approved in the Senate. At almost the same time, an almost unanimous Republican vote, now with close to no Chesnut support at all, approved the Southern Territories Bill. These twin measures, Sumner celebrated, would both grant freedom to the enslaved and make the Federal government “the custodian of freedom”, with the power to protect the freedmen in their liberty and rights. But, as examined previously, Lincoln vetoed the Southern Territories Bill to maintain control over the Reconstruction process. This decision had fateful consequences for the amendment. By then, many Northerners considered that the Congress was seeking to rebuke Lincoln, to show him that “his petty tinkering devices of emancipation and feeble plans for Reconstruction will not answer”, as the

New York Herald said. And indeed, given his refusal to accept the bill, Radicals now believed they ought to support a more radical version of the amendment.

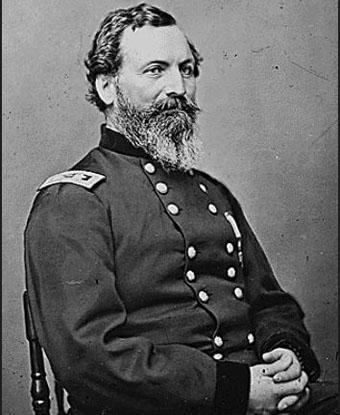

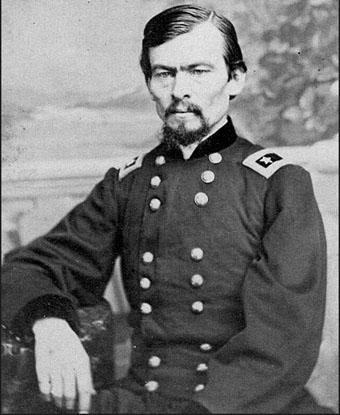

Then, another event profoundly changed the discussion around both Lincoln’s reelection and the amendment – John Wilkes Booth’s attempt on the President’s life. Just before the assassination, an “inconsolable” Sumner met with other Radicals, including Pomeroy and Wade, in a conference that “boded no good to Father Abraham”, a newspaper surmised. The main objective, a still embittered Davis admitted boldly, was “to get rid of Mr Lincoln”, who, in his view, had already practically secured the Republican nomination. As they discussed whether they would present a separate candidate in the Convention, with Frémont, Chase, Grant, and Butler all discussed, or whether they would call for a separate Convention, news of Booth’s attack arrived, and ended their efforts for the time being as almost all Northerners rallied around Lincoln and attacked his enemies.

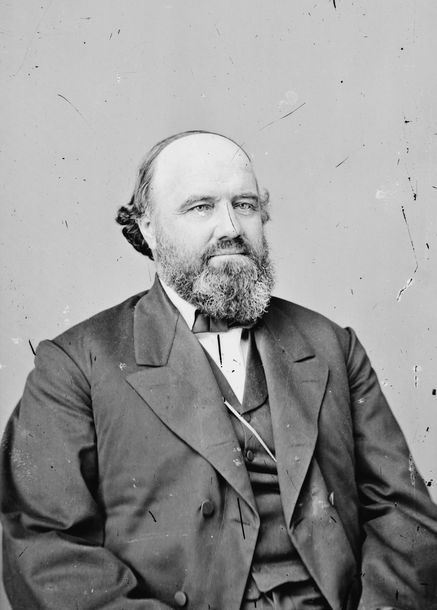

This resulted in the apex of the second political movement mentioned beforehand – the conservative cabal that wanted Lincoln to abandon the Radicals of his Party. The dream of a conservative coalition was one that refused to die, being proposed ever since the war started. But as the disagreements between Radicals and Moderates mounted, several Conservative Republicans and Moderate Chesnuts believed they could convince Lincoln to desert the Radicals, with their dogmatism and abuse towards him, and instead embrace a renewed “National American Party” that would follow his policies. The main architects of this scheme were the Conservative Republicans that hated the “monomaniacs” and their “devotion to the negro” as the

New York Times called them. This included Thurlow Weed, Seward’s ally and “alter-ego”; the Blairs, who after flirting with the Chesnuts now thought they could retake a leading position in the party; and moderate Chesnut politicians led by Samuel J. Tilden, a New York politico who was willing to recognize the end of slavery and advocate for unconditional victory, as long as this meant a “conservative, constitutional policy of

restoration”.

Most of these men suddenly forgot their hostility to Lincoln to aid him in his struggle against Chase, and for a time Lincoln seemed receptive to their overtures. Frank Blair, elected as a “Unionist” from Missouri, received Lincoln’s support for a bid to be Speaker of the House when the first session opened, the President offering to restore his Army commission whenever he wanted. The effort failed, but the thankful Frank Blair still launched a “savage” attack on Chase, accusing him of corruption in the Treasury Department. Blair then joined the attacks on Chase with more generalized attacks against Radicalism. Echoing Chesnut arguments, Blair lambasted “the revolutionary schemes of the ultra abolitionists”, which would result in the “amalgamation” of the races and the eradication of the States. Instead of Reconstruction, they should advocate

Restoration of each rebel state to “its place in the councils of the nation with all its attributes and rights”. Intimating that, in fact, the assassination attempt wasn’t the fault of Copperheads but of “the Negro worshippers” that wanted to “rid of the President by any bloody means, just as they want to elevate the Negro by any bloody means”, Blair thundered that they could not win their attempt to replace Lincoln.

By basically repeating the arguments the Chesnuts had wielded against the amendment and the Southern Territories Bill, Blair had taken things too far, misjudging both the values of Moderate Republicans and Lincoln’s own principles. Although he was a Radical, Thaddeus Stevens’s denunciation of Blair as “this apostate,” whose address was “much more infamous than any speech yet made by a Copperhead orator”, was one most Republicans would agree with. Ultimately, Lincoln was committed to Reconstruction, not Restoration, and he agreed with his Party that slavery had to be destroyed. He was, moreover, committed to the policies of land redistribution, limited Black suffrage, and Federal protection of the freedmen. The disagreement was not with objectives or principles, but with methods and practicability, and by asking Lincoln to abandon Republican ethos in favor of watered-down Copperheadism, Blair set himself up for failure. Remarking that Blair’s speeches meant “that another beehive was kicked over”, Lincoln refused to renew his commission as promised. Soon enough, Blair and Weed would come to fully support Tilden’s schemes.

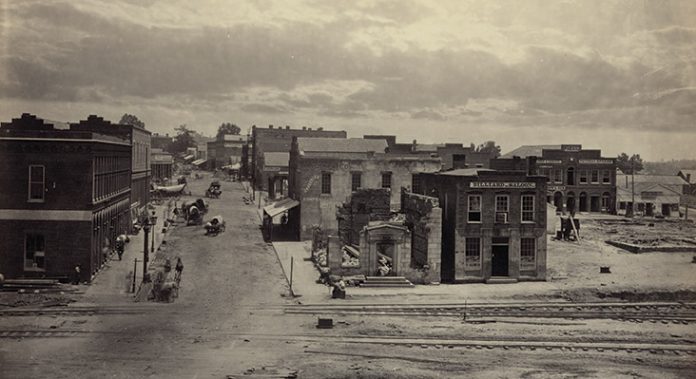

When the Republican Convention opened in June, the prevailing Northern mood exhibited a mix of extreme bitterness against traitors and effusive praise for Lincoln. “The Almighty has saved Father Abraham to led us on to victory and peace”, Republicans cheered in the streets of Philadelphia, as mock effigies of Booth were burned, and people held “Lincoln Logs”. “Do it again Uncle Abe”, said banners that depicted the President hitting Booth and also Confederates like Breckinridge and Lee. Three great portraits of Lamon, Lyon, and Reynolds, the ”martyrs of liberty who laid down their lives that Father Abraham, and thus the nation might live” were seen in the entrance of the Convention hall. In every corner there seemed to be speakers condemning the “rebel leader Breckinridge” who joined “cowardly and bloody assassinations to his long catalogue of horrendous crimes”. For organizing the assassinations, something virtually all Northerners believed, Breckinridge “would be hung from a sour apple tree alongside all his crew, and then suffer the everlasting torture of flames”.

In reaction to the prevailing pro-Lincoln mood, almost all Radicals had climbed aboard the Lincoln bandwagon, even if reluctantly. They, however, hadn’t abandoned their principles. Even if they had largely given up the idea that Lincoln could be replaced, they still believed that better protections than his Reconstruction plan offered had to be enacted for the safety of the Union and of the freedmen. Sumner and his allies thus had resuscitated the radical version of the constitutional amendment, which included not only the destruction of slavery, but also a guarantee of equality before the law. To ward off charges of consulting French codes, Sumner instead looked to the Declaration of Independence for inspiration. In its final form the amendment read:

SEC. 1. The United States is founded on the self-evident truths that people are born and remain free and equal before the law, endowed in certain unalienable rights. It is the purpose and duty of the government of the United States, and of the governments of the several States, to protect and defend these rights.

SEC. 2. Consequently, neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall ever exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

SEC. 3. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. Neither the government of the United States, nor the government of the several States, shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, recognized in the Constitution and the laws of Congress; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

SEC. 4. The denial, or the attempt to denial, any of the rights recognized in the Constitution or the laws of Congress, or to deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, by either the governments of the several States or by individual persons, acting on their own or in combinations, shall be a crime the penalty whereof the Congress shall be able to prescribe.

SEC. 5. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

The Radical amendment was the culmination of years of evolution of Republican thought. It did not only destroy slavery but represented an enlargement of Federal power that would allow the government, beyond a shadow of doubt, to protect the freedmen and Unionists, punish the rebels, and secure the legality and perpetuity of Reconstruction. Many, at the time and latter, were struck by the seeming leap from a simple abolition of slavery to a comprehensive centralization of government that allowed the National administration to define rights and enforce them against both the actions of States and individuals. But it merely represented the growing consensus in the Republican Party – that slavery had to be destroyed, rebels punished, the rights of the loyal protected by Federal power, and that equality before the law was the logical and just result of the war.

At first, it seemed like the passing of this radical version was an impossibility. Many Republicans fretted that it was too extreme, and the dissent of some conservative elements would be enough to defeat it given the thin Republican majorities. Indeed, the radical amendment went down in defeat in late May. It seemed like Republicans would instead vote for the simple conservative amendment, but several radicals close to Sumner then decided to vote against it, still holding out hope for passing the radical version. Not all Radicals agreed with Sumner. Thaddeus Stevens urged Sumner to not oppose the amendment any more, arguing that they could later enact its provisions through ordinary legislation or another amendment. The important part was destroying slavery as soon as possible. But Sumner wouldn’t budge, and with the votes of Chesnuts and Radicals the amendment failed. It had “been slaughtered by a puerile and pedantic criticism,” Stevens grieved, “by the united forces of self-righteous Republicans and unrighteous Republicans.”

The 1864 Republican National Convention

But an encouraging sign came soon, when pro-Lincoln congressmen voted with the Radicals to extend the session into the summer. Days later, Senator E.D. Morgan of New York opened the Republican National Convention by declaring, at Lincoln’s urging, that the Convention ought to be in favor of “an amendment of the Constitution as will positively prohibit African slavery in the United States” and “will give the National government the power to protect the loyal and just against the depredations of treason, extending the equal protection of the Constitution and the laws to all citizens”. Lincoln had, effectively, declared in favor of the Radical version of the amendment. Behind the scenes, his managers made it clear that this support was in exchange of Radical approval for Lincoln and later support for his Reconstruction plan. With the amendment having “remedied the deficiencies found in the plan hitherto followed”, a Radical replied, they could “all rally loyally around the Great Emancipator”.

At the same time as Lincoln extended this olive branch to the Radicals, his managers used the carrot and the stick to obtain the support of the grumbling conservatives. Unionism and patriotism was emphasized instead of party spirit and dogmatism. The Confederate President’s Uncle, Doctor Robert J. Breckinridge, declared that the Republicans had become an “Union party” that he would “follow to the ends of the earth”. A parade of politicians stopped by Lincoln’s summer residence in the outskirts of the city “to pay their respects and engrave on the expectant mind of the Tycoon, their images, in view of future contingencies”, reported John Hay. To the conservatives that disappointedly said it was merely an “Abolition Party”, Lincoln said that “the common end is the maintenance of the security and perpetuity of the Union,” and “among the means to secure that end” is the constitutional amendment “abolishing slavery throughout the United States and . . . giving the nation the power to enforce loyalty and respect for the Constitution.”

At the end, Radicals and Conservatives alike recognized that Lincoln was in a very strong position and that there was little hope of effectively challenging him from either side. Conservatives saw in him the only moderate, reasonable choice, and were satisfied that his veto of the Southern Territories Bill and his insistence on moderate Reconstruction in Louisiana were proof that he would adhere to a fundamentally conservative policy. Radicals were mollified by his support for the Radical amendment, celebrating that Lincoln still agreed with them on the objectives and meaning of the war, and believing that he could still be persuaded to take even more radical measures, such as universal Black suffrage. Their position was summarized by the abolitionists Lydia Maria Child, we thought they “have reason to thank God for Abraham Lincoln,” for “preserving him from traitors and assassins”, for despite “all his deficiencies . . . he has grown continuously; . . . it’s a great good luck to have the people elect a man who is

willing to grow.”

At the end, Lincoln was in complete control of the Republican Party, showing his political genius. “The opposition is so utterly beaten,” boasted David Davis, “that the fight is not even interesting.” Bowing to their defeat, even enemies of Lincoln that had denouncing him day and night, such as Weed’s New Yorkers or Radical Missouri Charcoals, voted with unanimity for him. With a “grand cheer for Union and Liberty”, the Convention unanimously endorsed Lincoln for President, for his “practical wisdom, the unselfish patriotism and unswerving fidelity to the Constitution”, endorsed the radical version of the amendment, and called for the “unconditional surrender and complete

Reconstruction” of the Confederacy. To punctuate this fiery Unionism, the Convention selected as Lincoln’s running mate the Kentuckian judge Joseph Holt, who had gone from being a part of Buchanan’s cabinet to a committed Republican fire-brand that enforced emancipation and the law in Kentucky against state officials that kept trying to nullify the laws of Congress and the proclamations of the President.

A few days later, the Congress took up the amendment again. Why did Lincoln support the amendment, many have wondered, when he had just rejected the Southern Territories Bill? This question has led many to decide that it must have been because the assassination attempt changed his thinking. In some ways, it did, for it reinforced Lincoln’s view that he had become “an accidental instrument in God’s hands”. But this was not a self-aggrandizing belief that he was the Chosen one, but a humble admittance that he still had a part to play in God’s grand design. If He had saved Lincoln, it was because he hadn’t fulfilled his part yet. Through this fatalism, the belief that “his destiny was controlled by some larger force, some Higher Power”, Lincoln had rationalized the heavy losses of the war as something the Creator intended to purge the nation of its sins. The sacrifice of Lamon, Reynolds, and Lyon, Lincoln came to regard as an act of God so that Lincoln could accomplish the great work He had set out for him.

Lincoln’s support for the radical amendment also shows his own inner growth, for he had come to believe firmly that the Federal government ought to protect the loyal, Black and White, and that all should enjoy equality before the law. “I am naturally anti-slavery”, the President wrote in a public letter. “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” Yet he recognized that being President had not “conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling”. His greatest duty was towards the Union, but preserving it made a necessity the “laying strong hand upon the colored element”. Given that the nation had asked for the aid of the Black man, it had to offer him protections and rights. If Lincoln allowed the war to end with the Black people that had “suffered for the cause of

their country” still enslaved, or still bereft of rights and victimized by unpunished rebels, Lincoln would be breaking the promise they had made when they first joined the cause of Liberty with the cause of the Union. “As a matter of morals, could such treachery . . . escape the curses of Heaven, or of any good man?”, Lincoln asked. The answer was a firm no, and for that reason Lincoln endorsed the amendment as “a fitting and necessary conclusion” that would permanently join the causes of “Liberty and Union”.

Finally, Lincoln could accept the amendment because unlike the Southern Territories Bill, which sought to wrestle control of Reconstruction away from him, the amendment merely extended what had by then become standard Republican doctrine. Lincoln, basically, agreed that slavery had to be ended, that Black people deserved equality and freedom, and that the Federal government had to have the power to enforce this against both states and individuals. He most likely would have taken all actions necessary for these goals with or without amendment, but accepting the Radical version, besides mollifying this faction and earning their loyalty, would secure the legality and stability of Reconstruction. The Southern Territories Bill, with its possibly unconstitutional program and stark differences from the President’s program, was not acceptable; the amendment was.

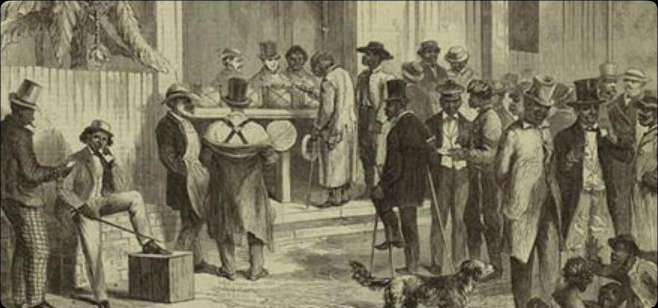

Some believe that Lincoln used other methods, including bribes and offers of political posts, to convince the Congressmen. Stevens for example would later remark, with some admiration, that “The greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America”. Nothing has been conclusively proved. But just a few days after Lincoln was renominated the Senate passed the radical amendment with unanimous Republican support, the opposition of some Senators who had supported the conservative version not enough. The ailing Owen Lovejoy, who would die just a few days later, was brought into the chamber to say a weak but convinced “aye”, clinging to life just to see “his great wish, that for which his brother and thousands of brothers, fathers, and sons gave their lives” accomplished. Then, in a tense session, the House voted. Abolitionists, including women and Black people, watched on as the votes were tallied. When it was over, every single Republican had voted in favor; every single Chesnut had voted against. But it was enough – with just two votes to spare, the amendment had passed.

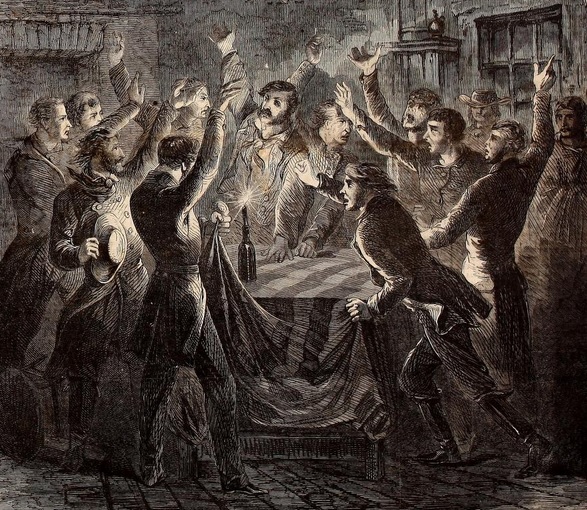

Celebrations after the passing of the 13th amendment

“And then you ought to have heard the galleries,” Senator Howe wrote his niece. “They sprang to their feet clapping hands, stamping, shouting, yelling, waving handkerchiefs.” “Members joined in the shouting and kept it up for some minutes”, a representative said, “some embraced one another, others wept like children. I have felt, ever since the vote, as if I were in a new country.” As a powerful sign of the Revolution, Black reporters and gentlemen were allowed into the House and Republican lawmakers embraced them and cried in joy with them, while surly Chesnuts slipped away in disgust and defeat. “In honor of this immortal and sublime event”, both Houses adjourned, and many lawmakers joined the celebrations outside. Jubilee quickly spread through the streets of Philadelphia, and then of the North as a whole, as great crowds celebrated its passage with songs, cheers and a great “thank you to Father Abraham”. “Senators shook hands, old friends clapped each other’s shoulders, women shed tears, and joy reigned!” a reporter wrote of the scenes in Philadelphia. “O Gentle Reader, it was good to be there”.

Lincoln received the news of the passage of the amendment at almost the same time as a Union League delegation came to congratulate him on his renomination. With unconcealed gratification, the President thanked the delegation for considering him “not entirely unworthy” or reelection. This, he said, reminded him of “a story of an old Dutch farmer, who remarked to a companion once that ‘it was not best to swap horses when crossing streams.’” Yet, turning to the Congressional messengers, he stated that maybe they had already crossed one of the most perilous streams, now that they had the amendment, “a King’s cure for all the evils.” Unnecessarily affixing his signature to the amendment, Lincoln expressed his gratification that they now had a measure that would truly “eradicate slavery and secure equality for all citizens”.

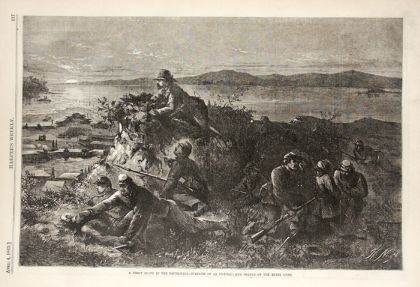

And so, the Republican Party took to the campaign trail in 1864 with Abraham Lincoln as its standard bearer and the 13th amendment, that abolished slavery and declared equality before the law, at the center of its platform. All Northern state legislatures controlled by Republicans soon ratified the amendment, and it was sure to be ratified in others more when they opened their sessions. However, most likely the ratifications of some Confederate states would be needed as well. The Republicans had thus committed themselves to building a new nation upon the ashes of civil war, but this had as its necessary corollary the unconditional defeat and dismantlement of the Confederacy by military victory. In the summer of 1864, it didn’t seem like this victory was fore-coming. The disorder brought about by the assassinations of Lyon and Reynolds had a negative effect in the Army’s organization, and a still defiant Confederacy appeared still capable of resisting. The jubilee and unity of June gave way to desperation in July and August, as schemes to replace Lincoln and a clamor for peace revived. Lincoln had been renominated, but whether he was reelected had still to be decided on the battlefields of Virginia and Georgia.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/battle-of-the-wilderness-large-56a61bd05f9b58b7d0dff4a2.png)