"A marvellous sweet child, of very mild and generous condition".

So what if that child had become a man? Here begins my second timeline.

The summer of 1553 marks a moment when English history balanced on a knife edge. The teenage King of England, Edward VI, had just begun to take control of his state, when he had been struck down with a major illness, possibly tuberculosis. Had Edward died, the throne would have been inherited by his sister, Mary “the Spaniard”, a radical half Spanish Catholic, whose own claims to the throne were dubious at best. Mary would have undone all of the work of Edward’s early reign, and denied England the great cultural flowering of the later 16th century. It is probably fortunate for us then, that around July 1553, the young King began to show a marked improvement, and by the time of his sixteenth birthday in October, his recovery seemed complete. Archbishop Cranmer ordered celebrations throughout London for this seeming proof of divine favour for the young King.

However, not everyone was so delighted. Mary the Spaniard, the elder sister of Edward, had been waiting now for over twenty years to clear her own name and restore the Catholic faith in England against the Protestant heretics; now her chances appeared to be retreating again. Once more, she was plunged into despair. Her life in England was now becoming intolerable. Over the autumn of 1553, she entered into correspondence with her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who agreed to begin another secret expedition to extradite her from England.

The young king was nonetheless extremely wary of his elder sister’s ambitions, and in November he summoned her down to London. Mary sent away his messengers, citing stomach pains, and assured her brother that she would set off for London as soon as she felt well.

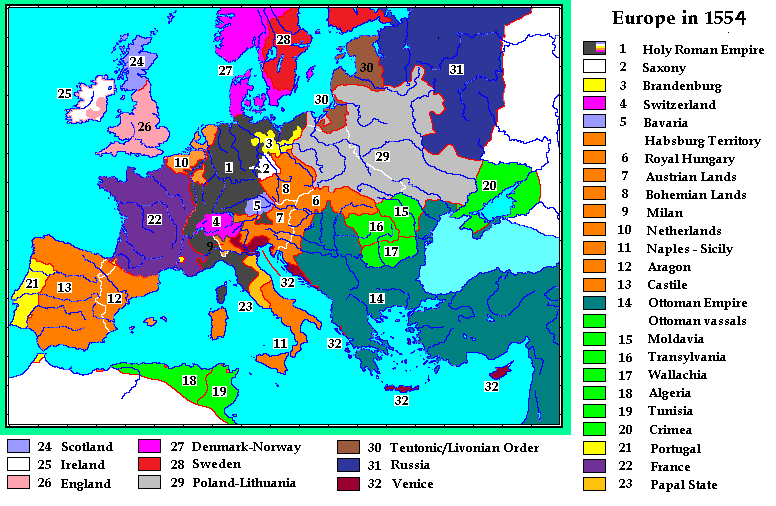

In London, this was largely accepted. The Duke of Northumberland, John Dudley, at this stage still had effective control over Edward’s government, and had begun the process of restoring the country to prosperity after the excesses of the past decade. At the end of 1553, Northumberland had bigger fish to fry than the stomach pains of an ageing Catholic bastard princess. Instead, his attentions were focused on Edward’s other sister, the twenty year old Elizabeth. Initially, Northumberland had been looking to the French for a marriage for the Princess, in order to build up an anti-Hapsburg bloc, but over that Christmas, an intriguing new idea hit him, spurred by the arrival in his company of a large group of Hanseatic merchants. To the far east there was a Christian monarch who opposed the power of the Pope who was mightier by far than Edward Tudor; the young Grand Prince of Russia, Ivan IV. In many ways, Ivan seemed the ideal match. Northumberland’s fertile mind immediately began to spin into action. If Russia could become an English ally, then there would finally be a definitive block on Hapsburg advances in the East; and a powerful alliance between Orthodoxy and Protestantism.

So it was, that on December 20th 1553, Northumberland sent an embassy led by Matthew Parker, the Dean of Lincoln, to approach Ivan with the possibility of an alliance. Neither Northumberland nor Parker could possibly have known that their actions would lead to what became one of the most enduring alliances of the period; and one that would eventually spell the doom of the Hapsburgs and their vast dominions. Indeed, for now, Parker complained bitterly of being forced to set out across freezing and stormy seas for Muscovy.

Princess Elizabeth was also rather unconvinced by the plan. In London, Christmas quickly descended into a violent struggle at court between herself and Northumberland, who was attempting to persuade the King to bastardize his sister in favour of his cousin, Northumberland’s daughter-in-law, Jane Grey. In this, Elizabeth won out. Her brother flew into a rage with Northumberland, and seriously threatened to remove Jane totally from the line of succession, let alone promote her. Chastened, the minister retreated. It was the first hint of the Edward that was to emerge; a man devoted to his family and their well being, and, like his father, only too willing to cut down overly successful ministers.

This state of confusion at court gave Mary her chance. One night in late December, evading the guards set up for her by Edward and dressed as a servant, she fled her home in East Anglia. There, accompanied only by her priest and a couple of maids she rowed out into the icy North Sea, where a Spanish ship was waiting, just beyond the reach of the beacons blazing on the shore. As the fugitives reached their saviours, a particularly violent wave swept them into the freezing waters, and only the sounds of their screams of cold alerted the Spanish to their presence. All four were hauled ashore, taken below decks, and wrapped up warm. Then, quietly, the ship sailed off into the night, heading for Antwerp. Mary Tudor had escaped.

She arrived in Antwerp on Christmas morning, 1553. There, she took Communion in the recently constructed Cathedral of our Lady, and gathered a large crowd of priests, before sending word to Vienna and Rome of the arrival of the rightful Queen of England on the Continent.

News reached London of Mary’s escape in the first week of 1554. Immediately, King Edward flew into a towering rage, and lashed out at his council. Northumberland and Cranmer survived the purge, others were not so lucky. William Paget, a former supporter of Edward Seymour, had only recently returned to favour with Edward, but the King had always regarded Paget as being too close to Mary, and too lax in his Protestantism. Now, aged sixteen, Edward was far more of a threat to Paget than he had been three years ago. The statesman was banished from court.

William Paget however chose not to take this treatment lying down. Encouraged by letters from Mary in Antwerp promising the support of the Emperor, in March 1554, he led a revolt from his native Staffordshire. Paget’s rebellion had two clear aims; to depose and murder Edward, and to replace him with a third candidate favourable to both himself and (he hoped) the Emperor; Princess Elizabeth. He aimed to marry Elizabeth off to his oldest son Henry, and so secure for himself the throne. Initially, Paget had huge popular support; the economic chaos of the past decade continued unabated, and the Midlands peasantry, though not as staunchly Catholic as their northern and Welsh compatriots, were becoming increasingly tired by the ceaseless royalist assaults on their church. By 1554, Paget’s rebels had established their headquarters in Lichfield, and had there hunkered down, awaiting a response from London.

While others at court lost their heads, the most senior of Edward’s advisers, Thomas Cranmer, kept his. Cranmer had by now been a dominant figure in English politics for over twenty years, and could remember well the previous great rebellions of 1536 and 1549, something King Edward could not. And Cranmer also had the friendship of one of England’s finest generals, a man even more experienced and intelligent than he was, the Marquess of Winchester, William Paulet. Paulet was so old that he predated the Tudor era itself; he had been born in Hampshire in 1483. He also had military experience, having led royal forces against the rebels in the Pilgrimage of Grace eighteen years previously. It was to this remarkable and energetic septuagenarian that Archbishop Cranmer and Northumberland chose to delegate control of the Royal army to.

Paulet led his forces with remarkable clarity of purpose. He gathered an army of French and Schmalkaldic mercenaries over the spring, and marched north towards Lichfield in July. There, the two Williams met, and Paulet managed to persuade Paget that he if only he lay down his arms, they could together manage to persuade the King to abandon his “brutish heresy”. Paget was not the first to fall for Paulet’s mastery of deception; the Marquess of Winchester had already followed three separate branches of Christianity with apparent devotion, and had found time to lecture both Henry VIII and Edward VI for not doing enough to persecute various heretical sects; even if he later became a member of such sects. The outcome of Paget’s rebellion was inevitable. Paulet managed to keep Paget in talks for a long time, while allowing his peasant army, eager to get back to their farms and families, to disperse of their own free will. The rest of the force was lured back southwards, and then wiped out in a short, brutal battle. William Paget was imprisoned in the tower, where he died six months later. For now, Edward VI was secure.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_VI#cite_note-34

So what if that child had become a man? Here begins my second timeline.

The summer of 1553 marks a moment when English history balanced on a knife edge. The teenage King of England, Edward VI, had just begun to take control of his state, when he had been struck down with a major illness, possibly tuberculosis. Had Edward died, the throne would have been inherited by his sister, Mary “the Spaniard”, a radical half Spanish Catholic, whose own claims to the throne were dubious at best. Mary would have undone all of the work of Edward’s early reign, and denied England the great cultural flowering of the later 16th century. It is probably fortunate for us then, that around July 1553, the young King began to show a marked improvement, and by the time of his sixteenth birthday in October, his recovery seemed complete. Archbishop Cranmer ordered celebrations throughout London for this seeming proof of divine favour for the young King.

However, not everyone was so delighted. Mary the Spaniard, the elder sister of Edward, had been waiting now for over twenty years to clear her own name and restore the Catholic faith in England against the Protestant heretics; now her chances appeared to be retreating again. Once more, she was plunged into despair. Her life in England was now becoming intolerable. Over the autumn of 1553, she entered into correspondence with her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who agreed to begin another secret expedition to extradite her from England.

The young king was nonetheless extremely wary of his elder sister’s ambitions, and in November he summoned her down to London. Mary sent away his messengers, citing stomach pains, and assured her brother that she would set off for London as soon as she felt well.

In London, this was largely accepted. The Duke of Northumberland, John Dudley, at this stage still had effective control over Edward’s government, and had begun the process of restoring the country to prosperity after the excesses of the past decade. At the end of 1553, Northumberland had bigger fish to fry than the stomach pains of an ageing Catholic bastard princess. Instead, his attentions were focused on Edward’s other sister, the twenty year old Elizabeth. Initially, Northumberland had been looking to the French for a marriage for the Princess, in order to build up an anti-Hapsburg bloc, but over that Christmas, an intriguing new idea hit him, spurred by the arrival in his company of a large group of Hanseatic merchants. To the far east there was a Christian monarch who opposed the power of the Pope who was mightier by far than Edward Tudor; the young Grand Prince of Russia, Ivan IV. In many ways, Ivan seemed the ideal match. Northumberland’s fertile mind immediately began to spin into action. If Russia could become an English ally, then there would finally be a definitive block on Hapsburg advances in the East; and a powerful alliance between Orthodoxy and Protestantism.

So it was, that on December 20th 1553, Northumberland sent an embassy led by Matthew Parker, the Dean of Lincoln, to approach Ivan with the possibility of an alliance. Neither Northumberland nor Parker could possibly have known that their actions would lead to what became one of the most enduring alliances of the period; and one that would eventually spell the doom of the Hapsburgs and their vast dominions. Indeed, for now, Parker complained bitterly of being forced to set out across freezing and stormy seas for Muscovy.

Princess Elizabeth was also rather unconvinced by the plan. In London, Christmas quickly descended into a violent struggle at court between herself and Northumberland, who was attempting to persuade the King to bastardize his sister in favour of his cousin, Northumberland’s daughter-in-law, Jane Grey. In this, Elizabeth won out. Her brother flew into a rage with Northumberland, and seriously threatened to remove Jane totally from the line of succession, let alone promote her. Chastened, the minister retreated. It was the first hint of the Edward that was to emerge; a man devoted to his family and their well being, and, like his father, only too willing to cut down overly successful ministers.

This state of confusion at court gave Mary her chance. One night in late December, evading the guards set up for her by Edward and dressed as a servant, she fled her home in East Anglia. There, accompanied only by her priest and a couple of maids she rowed out into the icy North Sea, where a Spanish ship was waiting, just beyond the reach of the beacons blazing on the shore. As the fugitives reached their saviours, a particularly violent wave swept them into the freezing waters, and only the sounds of their screams of cold alerted the Spanish to their presence. All four were hauled ashore, taken below decks, and wrapped up warm. Then, quietly, the ship sailed off into the night, heading for Antwerp. Mary Tudor had escaped.

She arrived in Antwerp on Christmas morning, 1553. There, she took Communion in the recently constructed Cathedral of our Lady, and gathered a large crowd of priests, before sending word to Vienna and Rome of the arrival of the rightful Queen of England on the Continent.

News reached London of Mary’s escape in the first week of 1554. Immediately, King Edward flew into a towering rage, and lashed out at his council. Northumberland and Cranmer survived the purge, others were not so lucky. William Paget, a former supporter of Edward Seymour, had only recently returned to favour with Edward, but the King had always regarded Paget as being too close to Mary, and too lax in his Protestantism. Now, aged sixteen, Edward was far more of a threat to Paget than he had been three years ago. The statesman was banished from court.

William Paget however chose not to take this treatment lying down. Encouraged by letters from Mary in Antwerp promising the support of the Emperor, in March 1554, he led a revolt from his native Staffordshire. Paget’s rebellion had two clear aims; to depose and murder Edward, and to replace him with a third candidate favourable to both himself and (he hoped) the Emperor; Princess Elizabeth. He aimed to marry Elizabeth off to his oldest son Henry, and so secure for himself the throne. Initially, Paget had huge popular support; the economic chaos of the past decade continued unabated, and the Midlands peasantry, though not as staunchly Catholic as their northern and Welsh compatriots, were becoming increasingly tired by the ceaseless royalist assaults on their church. By 1554, Paget’s rebels had established their headquarters in Lichfield, and had there hunkered down, awaiting a response from London.

While others at court lost their heads, the most senior of Edward’s advisers, Thomas Cranmer, kept his. Cranmer had by now been a dominant figure in English politics for over twenty years, and could remember well the previous great rebellions of 1536 and 1549, something King Edward could not. And Cranmer also had the friendship of one of England’s finest generals, a man even more experienced and intelligent than he was, the Marquess of Winchester, William Paulet. Paulet was so old that he predated the Tudor era itself; he had been born in Hampshire in 1483. He also had military experience, having led royal forces against the rebels in the Pilgrimage of Grace eighteen years previously. It was to this remarkable and energetic septuagenarian that Archbishop Cranmer and Northumberland chose to delegate control of the Royal army to.

Paulet led his forces with remarkable clarity of purpose. He gathered an army of French and Schmalkaldic mercenaries over the spring, and marched north towards Lichfield in July. There, the two Williams met, and Paulet managed to persuade Paget that he if only he lay down his arms, they could together manage to persuade the King to abandon his “brutish heresy”. Paget was not the first to fall for Paulet’s mastery of deception; the Marquess of Winchester had already followed three separate branches of Christianity with apparent devotion, and had found time to lecture both Henry VIII and Edward VI for not doing enough to persecute various heretical sects; even if he later became a member of such sects. The outcome of Paget’s rebellion was inevitable. Paulet managed to keep Paget in talks for a long time, while allowing his peasant army, eager to get back to their farms and families, to disperse of their own free will. The rest of the force was lured back southwards, and then wiped out in a short, brutal battle. William Paget was imprisoned in the tower, where he died six months later. For now, Edward VI was secure.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_VI#cite_note-34